“Translation is a powerful tool for sharing history and culture”

Originally published on Global Voices

Jayant Sharma is a writer, editor, and literary translator, who primarily works in Nepali and English. A staunch advocate for the global recognition of Nepali literature, he has translated over two dozen literary works. He is also the founder of translateNEPAL, an initiative that amplifies Nepal's literary presence worldwide.

Jayant contributes regularly to South-Asian journals, delving into topics encompassing Nepali arts, culture, and literature. Additionally, he is the author of ‘To Whom It May Concern,’ a poetry collection published in Australia. Global Voices talked to him via email about his translation work and literary inspirations:

Global Voices (GV): You've continued to contribute significantly to the field of Nepali literary translation. Can you share some of your recent translation projects and what drew you to them?

Jayant Sharma (JS): Recently, I translated Pradeep Gyawali’s poetry collection, ‘Bina Salikka Nayakharu,’ into English as ‘Unsung Heroes,’ slated for publication next year. Gyawali’s works, especially his poems, left a profound impact on me, showcasing his poetic brilliance and addressing pressing issues in Nepali society. I also finished translating Dr. Sangita Swechha’s short story collection, ‘Gulaf Sangako Prem,’ titled ‘Rose’s Odyssey: A tale of love and loss,’ set to be published soon. Living abroad, I resonated deeply with Swechha's stories, reflecting the struggles of the Nepali community across different geographies. I’m also working on translating Guru Prasad Mainali’s ‘Naso’ and Ramesh Bikal’s ‘Naya Sadak ko Geet,’ aiming to introduce these acclaimed works to a global audience. On a personal front, I’m working on a project ‘Whispers in the Mountain,’ a collection of short stories from Nepal featuring important works of 30 noted writers.

GV: As a translator who has delved into the works of various Nepali writers, what unique challenges and joys do you encounter when translating different literary voices?

JS: Each writer brings a unique voice, reflecting the rich tapestry of Nepali culture and experiences. The challenge lies in capturing the nuances of these voices, ensuring that the essence and cultural subtleties are preserved in translation. One must also dance with the rhythm of each writer’s prose or poetry, understanding the cadence and emotions embedded in the language. It’s like translating not just words but emotions, ensuring that the readers in a different cultural context can feel the heartbeat of Nepali literature. The joys, however, are boundless. Every writer adds a layer to the narrative, introducing me to new facets of Nepali life, traditions, and the human experience. The challenge, then, becomes a thrilling puzzle, solving which brings a deep sense of accomplishment.

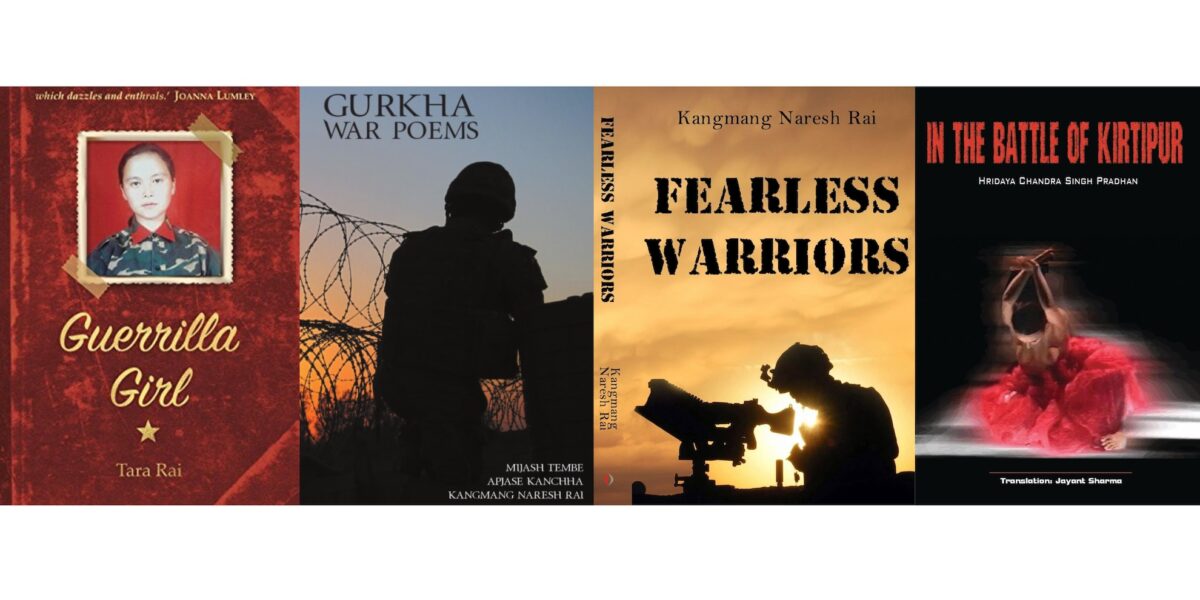

Book Covers of translations into English by Jayanta Sharma. Image via Jayanta Sharma. Used with permission.

GV: How do you envision the impact of translation in bridging cultural gaps and fostering a better understanding of Nepali literary heritage worldwide?

JS: Translation is a powerful tool for sharing the history and culture of one society with another. It's how we’ve come to appreciate the greatness of French, Russian, Spanish, Indian, or Chinese literature. This bridge between cultures is equally transformative in the context of Nepali literary heritage. Nepal, with its rich history dating back thousands of years, holds untold stories recorded in its literature. However, much of this past remains unknown to the world due to a lack of translation. Translation steps in as a linguistic conduit, breaking cultural boundaries and making Nepali narratives accessible globally. It provides a platform for Nepali authors on the international stage, amplifying their voices and contributing to the global literary conversation.

GV: Could you shed light on the challenges Nepali translators encounter when translating international literature, particularly when working with texts that are not available in English?

JS: Honestly, I haven’t translated much international literature into Nepali myself, but I do understand the multitude of challenges involved. One significant obstacle arises from the limited availability of the source text in Nepali, making it difficult for translators to capture the subtleties of the original language and style. Cultural contextualisation poses another hurdle, requiring translators to adeptly adapt references, idioms, and cultural nuances to resonate with Nepali readers. The challenge escalates when dealing with idiomatic expressions and wordplay. These linguistic devices may not have direct counterparts in Nepali, necessitating creative alternatives or risking a loss of intended meaning. Despite these challenges, translating international literature into Nepali presents a valuable opportunity for cultural exchange and enrichment.

GV: Share some insight on literal and thematic translation. Has your approach evolved over time, and how do you strike a balance between faithfulness to the original text and the need for adaptation to resonate with a broader audience?

JS: Personally, I strongly advocate for the power of thematic rendering in bridging the intricate nuances of one culture and language to another. In literature, a literal interpretation is like a dissonant note in a musical ensemble—out of tune and often disrupting the harmony. Looking back at my journey, my inclination towards a thematic approach has been unwavering. Despite occasional forays into literal translations during my early days, practical constraints led me astray. Over time, however, I’ve naturally gravitated towards a more nuanced and thematic orientation.

When I embark on a translation project, I undertake a thorough process. Multiple readings of the source material immerse me in its context, forming a mental roadmap for the translation journey and preparing the necessary resources. This approach requires translators to step into the author’s shoes, ensuring that the thematic rendition remains not just a translation but a faithful vessel for the genuine authenticity of the original work.

GV: As someone deeply involved in the literary scene, both as a translator and editor, how do you see the landscape of Nepali literature evolving in terms of international recognition and engagement?

JS: I'm not completely disheartened, considering that Nepali literature is gradually gaining recognition on the global stage. Though still in its early stages, there’s a pressing need for a significant push to firmly establish Nepal on the world map of literature. The lack of skilled translators, editors, and financial challenges pose obstacles. Publishers are reluctant to publish translated works, and the readership is not as encouraging.

Despite these challenges, some Nepali writers like Ramesh Bikal, Indra Bahadur Rai, Parijat, Buddhi Sagar, Krishna Dharabasi, Chuden Kabimo, Chandra Gurung, and Bhisma Upreti have managed to carve a niche in global literature. However, a significant portion of Nepali literature reaching the global stage is from writers who pen their works in English rather than the original Nepali, missing the crucial voices that demand global attention. As a translator and editor, I’m excited about the potential for more global interest in our Nepali literary works. As much of Nepal remains undiscovered in world literature, everything we bring forth offers a new realisation and perspective for global audiences. This depth has the potential to attract readers worldwide and create a literary buzz that travels far.

Another reason to celebrate is the growing influence of Nepali voices from around the world. The diaspora’s impact infuses Nepali literature with a dynamic vibe that resonates globally. Thanks to the internet, our literature serves as a virtual bridge connecting with readers everywhere, with social media serving as a vibrant marketplace for literary conversations.

Post a Comment