Political parties outsource the influence of voters in 2024 elections

Originally published on Global Voices

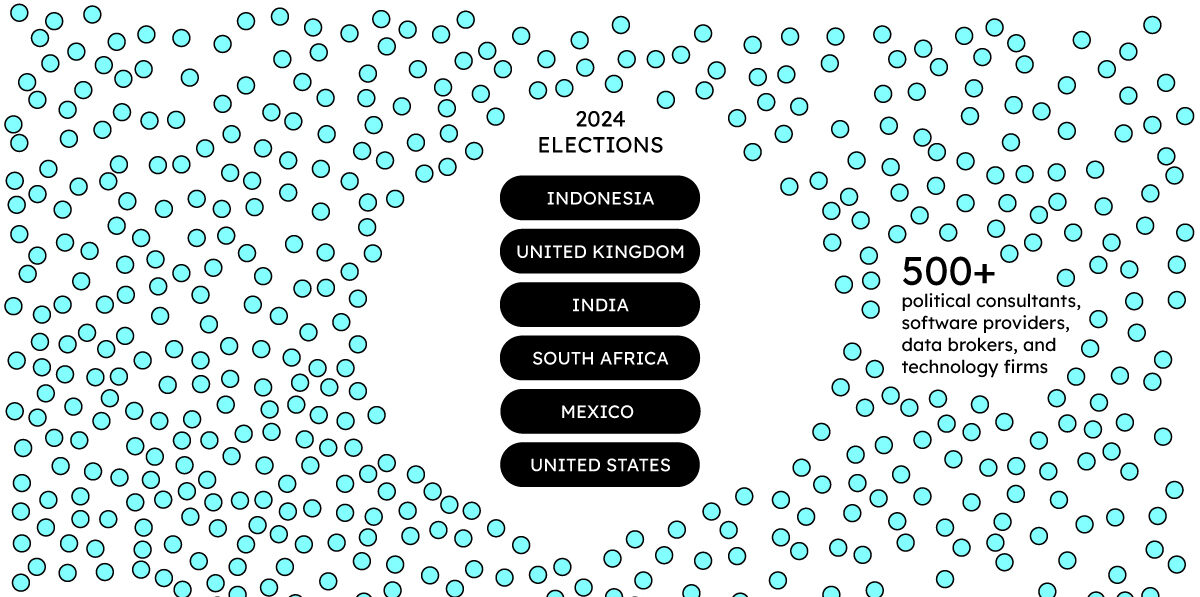

Illustration created with the Information of The Influence Industry Explorer by Yiorgos Bagakis for Tactical Tech, used with permission.

Whether debating if AI-generated deepfake videos and ChatGPT will disrupt trust in elections or if social media platforms will be able to monitor violence-inciting misinformation, digital technologies remain a key topic for 2024 election campaigns around the world.

Digital campaign tools and tactics are especially difficult to monitor as political parties often outsource the work to opaque private companies, agencies, and consultants. In 2023, for example, the Communist Party of Nepal (UML) worked with a freelance consultant to develop their campaign strategy, the Frente de Todos in Argentina paid Digital Ads S.A.S to develop their communications content, and Indonesian political parties hired “buzzer” agencies to spread their message on social media. Worldwide, there are over 500 political consultants, software providers, data brokers, and technology firms that make up the influence industry. This industry stands to profit from one or more of next year’s national elections, including in India, Indonesia, Georgia, Mexico, South Africa, the UK, Ukraine, and the US.

In the run-up to an election, political parties will use crafted messages to influence voters’ opinions and actions. Political actors rely heavily on platforms, such as Google Ad Library for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, India, and South Africa or Facebook’s political Ad Library for over 200 countries. However, candidates also pay private and covert consultants to design their social media strategy and broader online and offline campaigns. The companies in the influence industry collect data on our locations, our opinions, and our behaviors, create voter profiles representing what they believe to be our political interest and leaning, and, from this information, design campaigns, communications, and content to encourage us to, or discourage us from, voting for a certain party. Not only are these firms hired to produce informative and accountable campaigns, but they can also be hired to spread misinformation or create disruption within elections. For example, the infamous firm Cambridge Analytica, and their close collaborator AggregrateIQ, were hired to spread politically divisive and violent content through social networks to intimidate voters in Nigeria.

Despite playing a substantial role in managing political participation, these firms are often able to work out of public visibility and disregard important democratic processes. In countries with electoral transparency systems — such as Argentina and the UK — within which political parties must declare their financial spends on election campaigns, the invoices often show very little information about the actual services the firms provide, and at times the information is purposefully obscured. In Bolivia, influence groups don’t need to worry about the concerns of collecting data themselves when they can buy datasets on cheap CDs from people who were previously employed to produce that data for someone else. Even with data protection laws, supposedly transparent firms can still create “anonymous profiles” that disconnect users from their original data but still use this data to produce profiles to identify individuals and groups.

Through understanding these firms, and their role in the complex and increasingly unstable landscape of digital politics, we can begin to hold political groups to account and make more informed choices on voting day.

Illustration created with the Information of The Influence Industry Explorer by Yiorgos Bagakis for Tactical Tech, used with permission.

Should private firms take sides in politics?

The political ideology, especially the partisanship, of a firm has been important to the foundations of the data-driven influence industry. The media coverage of data-driven influence began in earnest after the success of data-driven tactics in Barack Obama’s grassroots-style campaigns for US president in 2008 and 2012. Many of the individuals involved went on to establish consultancy firms, including 270 Strategies, the Messina Group, and Blue State Digital, which all align themselves with “progressive” politics. In response to the visibility of these progressively aligned firms, Thomas Peters, a conservative blogger, wrote, “The only way to defeat Democrats was to learn from their tech advances, and then leapfrog them.” With this ethos in mind, he started uCampaign in July 2013 — a Republican party-aligned firm that develops campaign apps. In a similar case, Harris Media, a communications and marketing company, was founded by Vincent Harris, a conservative political strategist described as “the man who invented the Republican Internet.”

All of these firms have exported their work, resources, and politics worldwide, often gaining insights that benefit their agendas without impacting the places the consultant and staff of the firm live. For example, private firms have been testing tactics across various African countries before returning to France or the US. Their politics, in some cases, matches the “sides” they choose in their home country: Harris Media has worked with the UK Independence Party (UKIP), Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany, and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In contrast, Jeremy Bird, who founded 270 Strategies, worked with V15, a group opposing Netanyahu. In some cases, the companies work across various political groups, depending on who they have contacts with and who will pay for their services. For example, The Messina Group has worked with Enrique Peña Nieto, the former president of Mexico, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the prime minister of Greece, and Mariano Rajo, the former prime minister of Spain. The US-based values of these firms — that is, the politics they support, and that which they see as legitimate, as well as that which they see as advantageous — are embedded in their work as they influence politics around the world.

These firms can earn vast quantities of money. According to the US Federal Electoral Commission, which is one of the few places to give an insight into the money spent on these firms, Harris Media earned over USD 1.12 million in the last three years from US political groups. Crosby Textor (now CT Group) has been involved in campaigns in Australia, Italy, Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates, Sri Lanka, and Yemen. According to the Electoral Commission in the UK, as of 2010, Crosby Textor has made over GBP 8 million from working with the Conservative Party and has also made several thousand-pound donations to the party.

While these firms profit from impacting our politics worldwide, they remain opaque and unelected, and many of these firms manage and influence the political direction of political campaigns — and, therefore, the political environment — in several different countries. The companies collect data on individuals based in one country, analyzing the information to build profiles they can use to the advantage of their work internationally. The intelligence they hold on citizens creates risks, including data breaches, misuses of data, and changes of hands in political governance — especially those which come during or after divisive conflict. Their business structure — and often values — are focused on profit: content that brings them ad revenue or appeals to political parties with funds, rather than principles of political practices. The companies do not need to worry about whether voters are well informed, whether healthy deliberation is occurring among groups, or whether under-represented groups are being heard.

The rise of these firms, and the digital campaign tactics they support and engage in, is inextricably linked to increasing political polarization. This makes it important to understand and question the role of these firms in politics. Through asking questions, interrogating the firms, and building transparency, we can learn how to effectively regulate or manage our own political environments. The role of the influence industry is substantive, and identifying their political and profitable agenda is vital to understanding the magnitude of their power to influence political outcomes — and tensions — worldwide.

Post a Comment