Civic Media Observatory research shows how conservative narratives try to silence women online.

Originally published on Global Voices

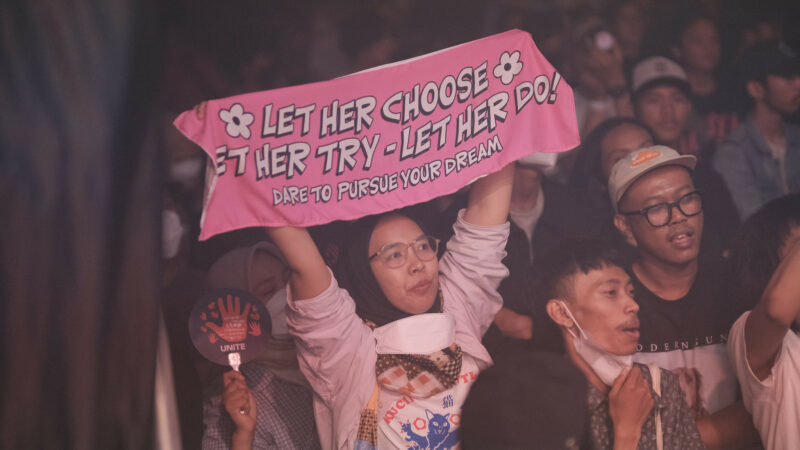

A music and art festival gathered young Indonesians who support the campaign against gender-based violence. Photo by UN Women/Putra Djohan. Source: Flickr account of UN Women Asia and the Pacific. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 DEED

This story is part of the Civic Media Observatory, where researchers investigate narratives in media ecosystems with a specific methodology. Learn more here.

Online bullying of women and girls in Indonesia skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this disturbing trend has continued and even intensified ahead of the February 14, 2024 elections.

Cyberbullying makes women more reluctant to participate online which exacerbates the gender digital divide. According to research conducted by the Alliance for Affordable Internet, women are more often the targets of cyberbullying than men.

The 2024 Indonesian election campaigns are intensifying cyberbullying. The wide reach of social media means that it is used as a campaign medium by parliamentary and presidential candidates. Each candidate has a special team handling campaigns online, whom digital rights activists and scholars call “cyber-troops”.

The activity of these online mercenaries are quite alarming, because they also organize cyber-wars among candidate supporters, as well as disseminate misleading information. And they particularly bully women.

Narrative 1 : “Cyberbullying is major obstacle to women’s full participation in society”

To build a safer environment in the digital world for Indonesia's women, some civil society organizations, activists, and artists have joined forces to fight cyberbullying in Indonesia through several campaigns. They are the ones promoting this narrative, alongside the women directly concerned.

Women and girls still face difficulty being active in the digital world. Online bullying makes them step back and be less active on the internet. Cyberbullying is a serious issue because it not only makes women less involved in the virtual world but also brings severe consequences in real life, e.g., feeling ashamed and threatened.

On top of that, women who become victims of cyberbullying find it hard to file reports with law enforcement. Most of them claim to have experienced victim-blaming, with police officers more focused on finding the victim's fault rather than on the perpetrators.

According to research, the current Indonesian legal framework is insufficient to protect victims. Other research was done by AwasKBGO, a civil society organization that analyzed the current regulations and practices aimed at addressing gender-based harassment.

Feminists and researchers argue that the patriarchal culture makes online bullying even worse. Women are still treated as second-class citizens, and this is showcased when women are more aggressively targeted when they speak up online.

How this narrative moves online

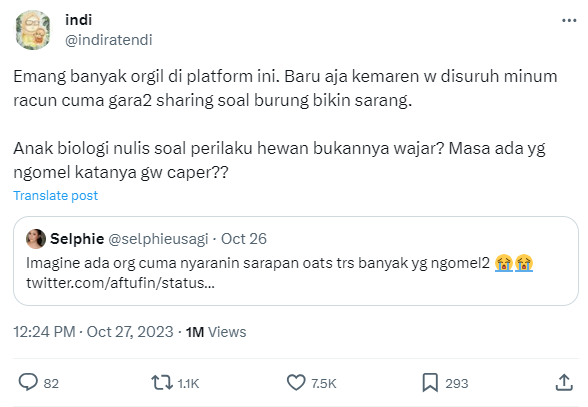

Indira Tendi is a wildlife biologist. She tweets that there are many “crazy” people on X, as she was threatened just because she shared her knowledge on somebody's thread.

Indira Tendi is a wildlife biologist. She tweets that there are many “crazy” people on X, as she was threatened just because she shared her knowledge on somebody's thread.

Verbal abuse is a common form of cyberbullying in Indonesia (we expanded the technical definition of verbal abuse to include harassment on social media). Some verbal abuses are very harming psychologically, e.g., “You're better dead” or “Just disappear from the earth.”

Tendi said somebody tweeted to her: “You'd better drink poison” when she was explaining how birds build their nests, her domain of expertise.

This item got positive score of +1 out +3 on our Civic Scorecard because she pushed back against the verbal abuse she got.

Narrative 2: “Politics is no place for women”

This narrative is mostly promoted by anonymous bots and conservative influential public figures, mostly from religious communities.

Patriarchal culture and religion have a strong influence on Indonesia's public life, and this is reflected in the pervasive belief that women should be confined to the domestic sphere. When women are criticized for participating in the political process, they often end up leaving politics.

In 2003, the Indonesian government decided to allocate a 30 percent quota in parliament for women. The quota was supposed to be a game changer for Indonesian women's representation in national politics. But in reality, women's representation in parliament is only at 24 percent. Among the reasons for this is the absence of organized training for women candidates and the irrational distrust of women's capabilities.

Online attacks ramp up during elections which now also involve cyber troops running campaigns in the digital world and targeting women. Women of all stripes are concerned: those running for elections, but also those actively involved in a campaign or trying to raise awareness on human rights issues.

Still, on a day-to-day basis, women in politics face persistent challenges from influential religious and political figures who question their political work. As the general election approaches, they must also endure cyber-attacks orchestrated by online factions, adding another layer of adversity to their already demanding roles.

How this narrative moves online

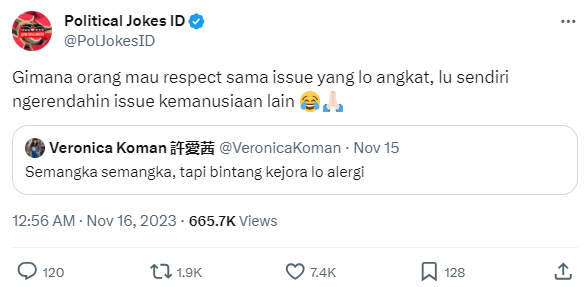

In this tweet, a bot account asserts that Veronica Koman, a human rights defender, does not deserve respect because she tweeted that people who defend Palestinians forget about the West Papuan people who have been repressed by the Indonesian government.

In this tweet, a bot account asserts that Veronica Koman, a human rights defender, does not deserve respect because she tweeted that people who defend Palestinians forget about the West Papuan people who have been repressed by the Indonesian government.

Veronica Koman is a lawyer and human rights defender living under self-imposed exile in Australia and who works with the people of West Papua. She spoke several times at the UN Human Rights Council to defend West Papuans, an advocacy for which she faced reprisals.

She has been accused by the Indonesian government of spreading unrest, and has faced a massive attack on her social media by government-related cyber troops, especially on X. She usually fights back, with strong comments that are often intentionally twisted and misconstrued by her opponents.

Koman's tweet, embedded here, says: “Watermelon watermelon, but you're allergic to the morning star.” The watermelon is a symbol used to represent Palestine, whereas the Morning Star represents West Papua. These symbols aim to avoid censorship.

This item got a negative score of -1 out of -3 on Our Civic Scorecard because this kind of comment was an example of attempts by cyber troops to silence women who work on political and human rights issues.

Glimmers of hope

A glimmer of hope emerged with the 2022 approval of the bill addressing sexual violence and the revision of the Law on Information and Electronic Transactions. These laws were designed to regulate cyberbullying against women.

However, advocates claim that it is crucial to closely monitor their implementation, as they are susceptible to misuse by malicious individuals and authorities to criminalize the work of human rights defenders and attack victims of gender-based violence.

Also in 2022, Indonesian women in parliament signed a declaration to end the violence against women in politics. They were supported by UN Women and civil society organizations. On that occasion, Puan Maharani, the first Speaker of the House of Representatives in Indonesia, said:

From gendered double standards to sexual harassment, the unique obstacles faced by women running for offices need to be brought into sharp relief. Today, we gather here to convey a clear message: we must act together to break the culture of silence that perpetuates violence against women.

Post a Comment