Maksym Chernov spent nine months fearing Russian persecution

Originally published on Global Voices

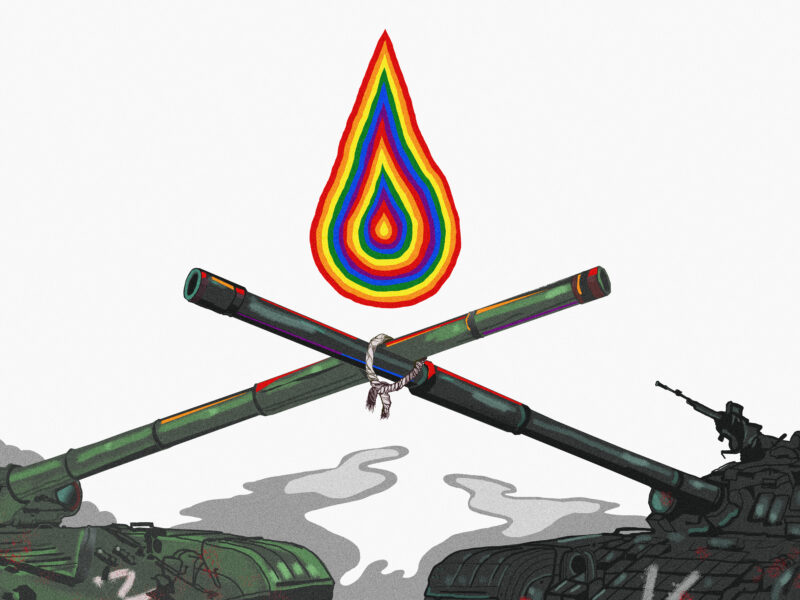

Image by Valeo Kopysov for Global Voices, used with permission.

This story is part of a series of essays and articles written by Ukrainian artists who decided to stay in Ukraine after Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022. This series is produced in collaboration with the Folkowisko Association/Rozstaje.art, thanks to co-funding by the governments of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia through a grant from the International Visegrad Fund. The mission of the fund is to advance ideas for sustainable regional cooperation in Central Europe.

Maksym Chernov, 22, describes himself on Instagram as a queer punk and vegan abolitionist who advocates for the abolition of slavery, both formal and informal. For nine months, he lived in the then-Russian-occupied Kherson and survived because he barely went outside. Some other members of the LGBTQ+ community there were less lucky: during their occupation, Russian forces kidnapped several LGBTQ+ activists, took a lesbian woman to a forest and threatened her, and shot a gay man in the leg after finding the Hornet app (a queer social network) on his smartphone.

‘Those in latex’

Maksym Chernov is a non-binary transgender person (he uses the pronouns he/him) who has repeatedly heard offensive and unfair stereotypes about his gender identity, which often emerge through a lack of knowledge or awareness. Once, before a lecture by a Ukrainian feminist LGBTQ+ charity, Insha (the feminine form of the word “other” in Ukrainian), one of the guests derided transgender people as merely “those who wear latex.” Maksym was outraged by this state of affairs, so he joined Insha to help educate their community.

“I want society not only to know about the existence of transgender people but also understand who they are, that they are normal people,” he said.

In 2019, Chernov started leading discussions at Insha. He does not like the word “lecture” but prefers to offer topics and encourage participants to think and discuss among themselves.

Conversations about transgender people are complicated not only by social stigmatization but also by binary ideas about gender and sexuality. For example, listeners have provided the following arguments: “Gender is innate, natural, physiological” or “A true woman wouldn't want to become a man.”

Together with the Insha team, Chernov planned to expand the educational program, but the full-scale Russian invasion prevented him from putting this idea into motion.

Chernov was used to stockpiling necessary supplies, so he managed to do this before the full-scale war. On the night of February 23, he was working at his computer when he heard explosions. Although he had anticipated the possibility of shelling, the sounds took him by surprise: “It was a shock. My faith in people faltered once again.”

After four days of the offensive, the Russians encircled Kherson.

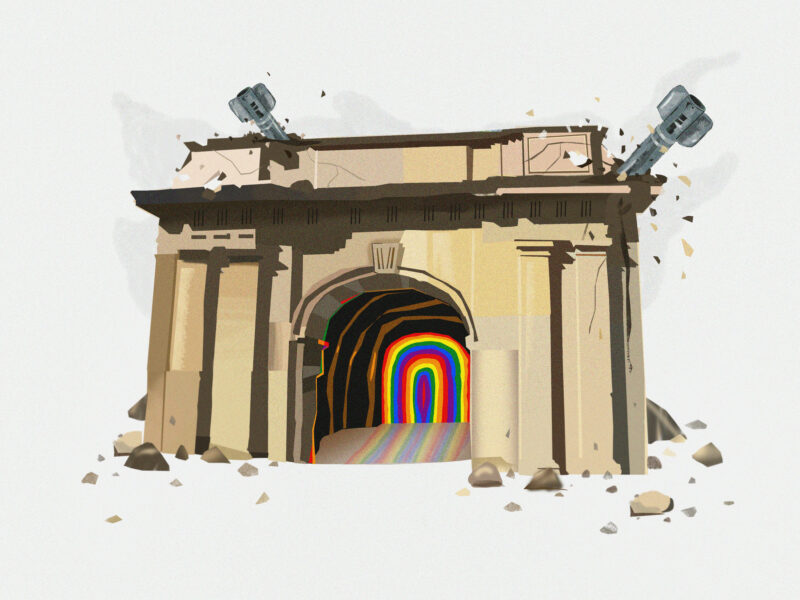

Image by Valeo Kopysov for Global Voices, used with permission.

While Ukraine's armed forces were defending the city, the citizens were getting ready “to meet” the enemy in the city: volunteers were preparing Molotov cocktails, and welders were making anti-tank obstacles. Chernov's shock gave way to lethargy. In the beginning, he didn't leave the house: “I could do nothing. I was only thinking that I'll die soon.” Eventually, he reached acceptance: he wouldn't die as soon as he thought, so he needed to live on. When he ventured into a supermarket to replenish his food supplies, all he found were clothespins — the Kherson residents had bought the rest out of panic.

On March 1, there was still fighting in the city streets, but in two days, the Russians took the Kherson Regional State Administration building.

A manhunt

During the occupation, fearing arrests and violence from the Russians, residents tried to avoid leaving their homes. Basic human rights were threatened, so Chernov considered it senseless to focus specifically on LGBTQ+ oppression amid the occupation. Amid Russia's human rights violations, “What additional, so to speak, non-basic rights can we talk about?” he asked rhetorically. Knowing the Russian state's homophobic policies, members of the LGBTQ+ community took extra precautions to avoid the occupiers. Chernov said:

Те, що людина належить до ЛГБТ спільноти, російські військові могли дізнатися лише, якщо цілеспрямовано шукали інформацію про цих людей. До того ж якийсь херсонський гомофоб міг знайти когось з ЛГБТ-спільноти, натовкти йому пику, і ніхто йому нічого за це не зробить, адже в місті не було поліції.

Russian military men could find out that a person belongs to the LGBT community only if they deliberately searched for information about such people. In addition to that, some local homophobe could find an LGBT person, kick them in the face, and no one would do anything about this because there was no police in the city.

In May 2022, the occupants broke into the Insha offices, smashed furniture, stole office equipment, and destroyed LGBTQ-themed paraphernalia. The Ukrainian LGBTQ+ center, Nash Svit (from Ukrainian: “Our World”), wrote in their report that a local resident directed the occupants toward the community center. But Maryna Usmanova from Insha doubts this claim: “We have never been hiding. We have an office in the city center. If you simply google “LGBT Kherson,” our address would pop up.” But Chernov does agree that LGBTQ+ activists were hunted. The Russians collected data and searched for community members, so some of them ended up “in the basement” (a Ukrainian expression referring to Russian fighters and their local collaborators using basements as makeshift prisons to detain and torture dissenters and those with pro-Ukrainian views). In one widely covered case, the Russians kept Oleksiy Polukhin, an LGBTQ+ activist, at a local detention center for two months.

Everyday life under occupation

Chernov was spending all his time at home in the city center: he was knitting, drawing and embroidering, and sometimes posting to social media to maintain contact with the world outside — until the Russians turned off the Ukrainian mobile connection. Chernov hoped the network would be repaired, but weeks passed, and the connection was not restored. Finally, he had to give up and buy a Russian SIM card, but the Russians had blocked Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and almost all the Ukrainian apps.

“I have noticed that I was paying no attention to the reality, losing contact with it. That's why I started to record and write down my observations from the occupied city,” Chernov said.

Despite having the means to occupy himself at home, Chernov wanted a larger purpose. He was always concerned about environmental pollution, and in 2021, he worked at Kherson's first waste sorting center. He assumed that talking about the environment and responsible consumption might be safer than LGBTQ+ activism.

On one of the local Telegram channels, Chernov posted an invitation to a free lecture on environmentally responsible lifestyle. In response, he received a single message: “Are you a fool? What kind of environmental issues matter now?! Join the military.” Maksym asked the person whether he was in the military, but he answered that he had left the city.

The lecture did not happen, but Maksym continued to take care of the environment, just as he did prior to the war, by sorting garbage and composting organic waste.

Evacuation

During the entire occupation, there had not been a single “green corridor” in Kherson. Everyone who wanted to leave did this on their own or with the help of non-government organizations.

The road ran through dozens of Russian checkpoints where those passing were thoroughly searched and questioned. They were asked whether they had relatives or acquaintances in the Ukrainian armed forces, stripped, and searched to determine whether they had patriotic tattoos, which the Russians claimed were evidence of “Nazi” ideals.

The charity Insha evacuated over 200 women and LGBTQ+ people to Ukrainian-controlled territory. The wife of one Ukrainian soldier approached Insha to help her leave after she was gang-raped by a group of Russians. Maryna Usmanova said Insha contacted a local volunteer who was taking people out in a rowing boat. He said he would take her at 1:00 a.m. from one of the piers. Even though it was dangerous to walk the streets at night, everything went well: after some time, the woman informed Insha that she had reached safety.

Chernov was not actively engaged in the evacuation efforts and decided he would not leave the city.

“I knew there were 30–40 checkpoints between Kherson and Mykolayiv. This road was gravely dangerous for an ordinary person, not even to say about transgender people. No one could tell what would come to mind for the Russian soldiers there. It was scary.

The Armed Forces of Ukraine liberated Kherson on November 11, 2022, but the Russians continue shelling the city almost every day from the still-occupied left-bank part of the Kherson region. Maksym Chernov finally left Kherson in March 2023. At first, he lived in Olexandria in the central Kirovohrad region; in June, he moved to Kyiv.

Wartime stories from Ukraine

Global Voices published a series of essays and stories written by Ukrainian artists who decided to remain in the country after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

Post a Comment