Originally published on Global Voices

Nathan Matias rides into the Yokuts Valley, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains east of Fresno, CA. Photo by Ivan Sigal (CC BY 4.0)

This article is part of a series by J. Nathan Matias for a 500+ mile bicycle ride in June 2023 that is raising funds for Rising Voices, Global Voices’ endangered/Indigenous language program, and the Central California Environmental Justice Network. Donate to the initiative here.

I'm Nathan Matias, a Guatemalan-American writer and academic who journeys through landscape, ideas, and histories on two wheels. This June, the writer and media artist Ivan Sigal, who is also Global Voices’ Executive Director, and I spent six days cycling through California’s Central Valley meeting people, making media, and collecting stories. We are also raising funds for the Central California Environmental Justice Network and Global Voices.

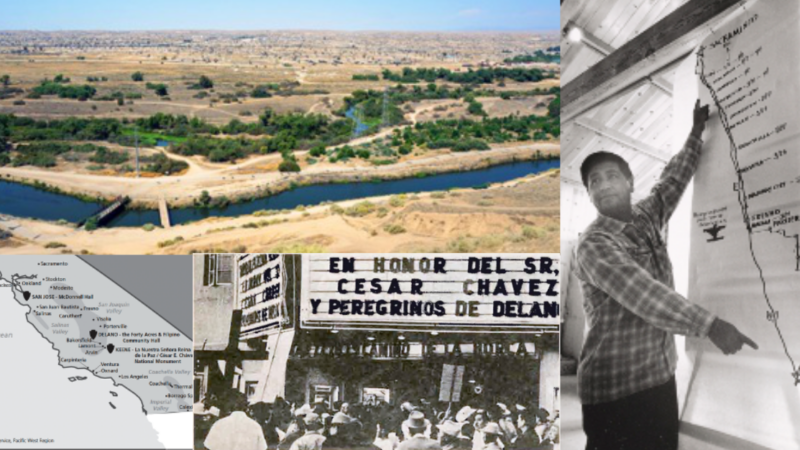

When the two of us set out on our 550-mile bicycle storytelling adventure in the footsteps of the 1966 March, we were chasing a legend, seeking a conversation, and trying to understand a region that will shape the shared future of our planet.

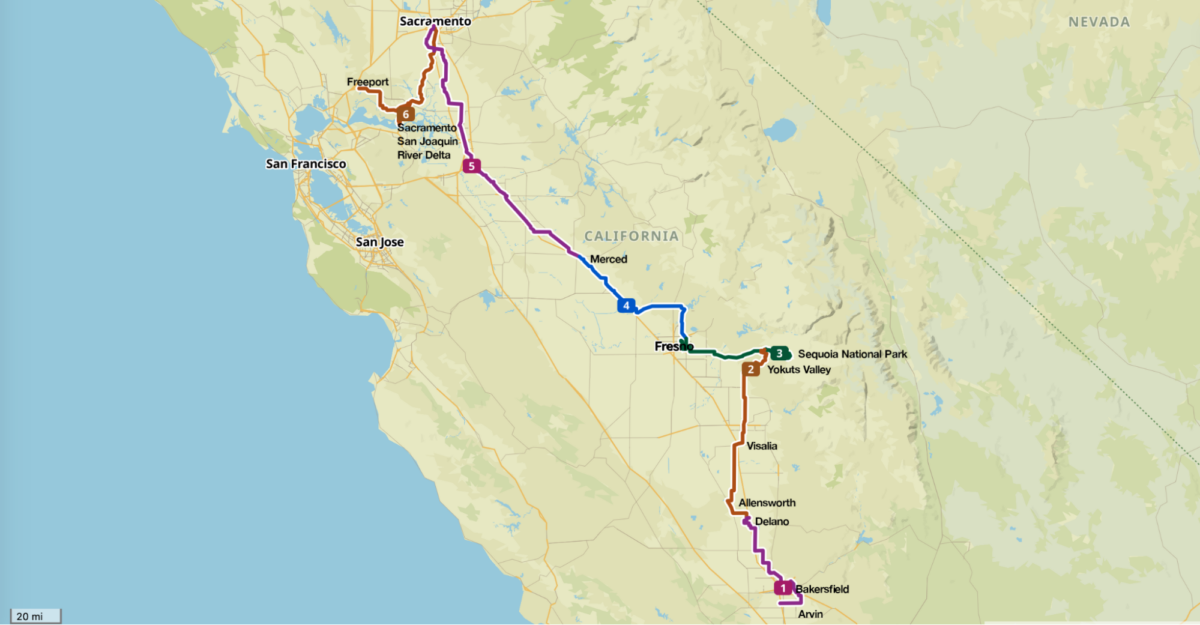

Nathan and Ivan's ride route from Bakersfield to the Bay Area: Source: Open Street Map

I first imagined our ride on a snowy December night in Ithaca, New York, after rushing into my local grocery store. Although I was a research fellow at Stanford University in California’s Bay Area for the year, I had evacuated the area and returned to New York after air pollution nearly paralyzed me with an asthma attack. Stuck indoors in the freezing winter, I was watching documentaries about California history from what felt like the wrong side of the continent. When a box of mandarins from Reedley, CA captured my attention at the grocery store, I knew I wanted to learn their story.

On cycling, chicken shit, and alternate futures

Cycling through Pajaro, California after the devastating flooding of April 2023, J. Nathan Matias wonders what his life might have been if his body had withstood the dangers of farm labor.

Five months later, as we descended from Sequoia National Park at the midpoint of our ride, we glimpsed Reedley’s orange groves framed between the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas. By that point, the oranges had become a plot device in the much larger story of the climate, labor, and future of California's Central Valley.

Mapping a different kind of bicycle tour

Bicycle tours tend to prioritize exquisite landscapes, but since our ride is also a journalistic exercise, we needed to adopt a different philosophy of route-making.

(L) Orange groves in Reedley and Orange Cove California. (R) Mandarins grown in Reedley at a grocery store in Ithaca, New York. Photos by J. Nathan Matias.

As I write this, I am on the plane back to my home in Ithaca, New York. Looking out the window, I can trace our path along highway frontage roads and delta levees that stretch for hundreds of miles. From this distance, the Central Valley can seem like an impending disaster—an impossible dream that a century of extraction and injustice are bringing to the point of collapse. As the Fresno journalist Mark Arax writes in The Dreamt Land, “the valley had been doomed from the get-go by its compulsion to intensify farmland, and it was a life’s work to write about the doom.”

In contrast with the harsh, engineered landscape, we met people with remarkable creativity, resilience and hope while riding at the pace of what Paul Salopek calls “slow journalism.” We spoke with farm workers, politicians, scientists, parents, journalists, and a group of high school students on their graduation day. We watched egrets wheel and hunt over a wetland preserve, and on one mountainside at dusk heard the story of a grieving woman about to bury her husband of 44 years. Everywhere we went, we encountered people who are working to document the challenges their communities face and organize for change.

Day Zero: Arvin and Weedpatch Camp

Cesar Aguirre, Oil and Gas Director at the Central California Environmental Justice Network. Photo by Ivan Sigal (CC BY 4.0)

This oil derrick in Arvin, California is located next to a school. Photo by Ivan Sigal (CC BY 4.0)

Oil derrick in Arvin, California, located just a few yards away from the backyards of residents’ homes. Photo by Ivan Sigal (CC BY 4.0)

The evening before setting off, we visited Arvin, California, where local community scientists do air quality monitoring to protect their schools, churches, and families from oil well air pollution. We also visited Weedpatch Camp, a migrant labor camp built in the 1930s for climate refugees from Oklahoma. It's still used today for migrant laborers in the Central Valley.

Arvin, California: Lost futures, past hopes, deferred promises

“Owners no longer worked on the farms. They forgot the land, the smell, the feel of it, remembered only that they owned it, what they gained and lost by it.”

Day One: Bakersfield to Delano

Clockwise from top left: Nathan poses in front of the bicycle lane in Bakersfield; Ivan rides between rows of farmworkers outside of Bakersfield; View of the Kern County Oil Field north from Panorama Park in Bakersfield; Ivan takes photos of the Kern County Oil Field north of Bakersfield. Photos by J. Nathan Matias and Ivan Sigal.

Our ride started at the Vagabond Inn in the south of Bakersfield. From there we set out for the California Fruit Depot, a roadside gift and fruit packing warehouse that caters to travelers arriving in the Central Valley from the Great Basin through the Tehachapi Pass.

After a drink of fresh orange juice, we rode between derrick pumps and orange groves to Panorama Park in Bakersfield, which overlooks oil fields that funded San Francisco's Golden Gate Park until 2016. For generations, a park made famous by countless movies and the 1960s Summer of Love had depended for funding on the profits from oil extraction hundreds of miles away: an almost equally large oilfield sited near schools and people’s homes. Looking out over the oilfield, we met Cesar Aguirre, Oil and Gas Director at the Central California Environmental Justice Network, who told us how communities are managing the health impacts of gas leaks from Bakersfield’s oil wells.

Ivan Sigal, Elisa Lopez, Mariah Lopez, Danielle Mosqueda, and J. Nathan Matias outside The Forty Acres. Photo courtesy the Lopez family.

After riding through 70 miles of grape vineyards and orchards of almonds, pistachios and oranges, we arrived at The Forty Acres in Delano CA. This garage and gas station was also the first home of the United Farm Workers of America, the union that marched to Sacramento in 1966. Our visit coincided with that of a group of high school students who had come to the historical site to take graduation photos!

Hunger strike and high school graduation: A visit to The Forty Acres

Renowned as the site of labor activist Cesar Chavez's 1968 25-day hunger strike, The Forty Acres is slated for incorporation into a national park being considered by the US government.

Day Two: Allensworth, Visalia, and into the Sierra Nevadas

Clockwise from top left: Ivan Sigal, J. Nathan Matias, and Randy Villegas; Colonel Allensworth's house in Allensworth; Climbing up to Sequoia National Park; Yokuts Valley. Photos by J. Nathan Matias and Ivan Sigal.

We started the day with a trip to Allensworth, a town founded in 1908 by former Black slaves to secure their freedom. The town declined after it was abandoned by racist railroad and water companies. It's now a state park. I'm planning to write more about Allensworth later this summer.

In Visalia, we met with Randy Villegas, a political science professor at the College of the Sequoias who is also the only Latinx person on Visalia’s school board. Randy spoke with us about the state of education for Latin-American young people and his efforts to support the next generation of civic leaders in Central California.

The Boomerang: Education and civic engagement in California's Central Valley

“Political scientists often believe. . . that young people with family members who are not U.S. citizens are less likely to be civically engaged because they can’t learn it from their parents.”

We ended this very hot day by putting ice down our backs and climbing 3,000 feet up into the Sierra Nevadas, finishing at a campsite and diner in the Yokuts Valley at the foot of Sequoia National Park.

When they caught sight of us, the staff at the diner understood what we needed. “Would you like dessert first?” they asked. There was only one way to answer!

Day Three: Descent to Fresno

Clockwise from top left: Melissa Montalvo of the Fresno Bee; Dirt road in Sequoia National Park; Ivan Sigal's second breakfast; Dinner with Farmworker Community Scientists in Fresno. Photos by Ivan Sigal and J. Nathan Matias.

On Day Three we rode toward the snow line into Sequoia National Park. We then descended back toward the Central Valley, past the town of Reedley, where the mandarins from my supermarket in New York originated. As we descended, the temperature spiked, and a hot headwind swept up the hills as we rode west. Our route intersected with the Friant-Kern Canal, a key water supply for those orange groves, and for much of the Central Valley. The foothills of the mountains were already dry with the heat of early summer, despite the spring’s torrential rains.

We ended the day in Fresno, where we met with Fresno Bee journalist Melissa Montalvo and shared dinner with farmworker community scientists who are developing techniques to fend off heat stroke when employers deny workers basic health protections.

On loving and understanding our communities: Journalist Melissa Montalvo in Fresno, California

“In the hands of Melissa Montalvo and other journalists, journalism is a mirror for a community with the majority of Fresno's population and a minority of its power…”

Day Four: Dashing to Merced to beat the heat

Clockwise from top left: The Friant-Kern Canal outside Fresno; Soda Machines in Fresno out of order after flooding disrupts the city's water; J. Nathan Matias eats fruit at a fruteria outside of Merced; J. Nathan Matias rides along a wall of hay near Madera.

Warned by farmworkers that the temperature was going to be 99F (37C), we changed our plans and rode out early for the Friant Dam, part of the vast Central Valley project that re-engineered the region's terrain into the massive and unsustainable agribusiness epicenter it is today. California's water system has been overwhelmed by the unrestrained expansion of agriculture and population growth. Newly introduced regulations require significant cuts by 2040—potentially leading to the retirement of up to a million acres of currently cultivated farmland.

Arriving in Merced for a late lunch of pizza and ice cream, we were forced to change our plans again, as Ivan's rear tire blistered and burst in the heat.

While Ivan hunted down a new tire bike, I contemplated an issue of astonishing scale and complexity—with the state running out of water, how could California retire and repurpose farmland without crashing the economy? We had dinner that evening with Dr. Angél Santiago Fernandez-Bou at University of California Merced, and a group of grad students who support community science on land use and environmental health. Dr. Fernandez-Bou has just published a new paper modeling ways that California could retire farmland, improve environmental health, and generate new jobs in the region.

Feeling the heat: Community science and survival in Fresno, California

“Extreme heat is a common experience for farmworkers in California, with 20 days out of every year exceeding safe working temperatures—a number expected to increase to 54 by mid-century. . .”

Day Five: The March to Sacramento

Clockwise from top left: Ivan Sigal rides out of Merced on a fresh tire; Ivan Sigal at the Cosumnes River Preserve in Galt; Puncture thorns in Nathan's rear tire; Trees on the levee along the Sacramento River. Photos by J. Nathan Matias and Ivan Sigal.

The 1966 Farmworker march grew to thousands of people along the road between Merced and Sacramento. International media started to pay attention, national politicians arrived to support the cause, and by the time the “peregrinación,” as the workers called their effort, arrived in Sacramento for Easter Mass, the United Farm Workers had won their first union contract.

As Ivan and I rode 142 miles through fierce winds toward Sacramento, I listened to “De Colores,” the Spanish folk song that farm workers had sung on the road to the state Capitol. This anthem of Catholic renewal in the 20th century imagined the colors of spring as a symbol of life, love, hope, and a world where people found common humanity across our superficial differences.

“De colores” helped me keep perspective as we stopped for train crossings and powered against gale force winds. Then I rode onto a bed of puncturevine, or “baby head” thorns, had to change both tires, and then sprung a slow leak. Out of spare tubes and chasing the sunset, we spent the last few hours to Sacramento stopping every 30 minutes to pump up my tires.

Riding through wetland preserves toward the Sacramento River levee, where some of the most dramatic photographs of the movement were taken in 1966, I was suddenly overwhelmed by the appearance of greater ecological diversity, in comparison with the genetically engineered monoculture crops of the last five days. Crossing the Sacramento River into the city, I thought of the farmworker who had walked barefoot into the city carrying a cross in 1966. After days in the dry heat, we could taste the moisture.

Arriving exhausted at our hotel as the sun set, we ordered pizza, spent several hours patching inner tubes, and prepared for our final day.

Day Six: From Sacramento into the Delta

Clockwise from top left: Ivan Sigal rides along the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta; Hector Amezcua meets with Nathan and Ivan in front of the Sacramento State Capitol; Ivan drinks a much-needed coffee in Isleton; Wind turbines at the Shiloh Wind Farm near Bird's Landing. Photos by J. Nathan Matias and Ivan Sigal.

We started our final day at the State Capitol in Sacramento where Cesar Chávez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Iltiong, and thousands of others had celebrated the end of the Farm Worker March in 1966. Seeing the Capitol made me think about the legacy of the 1966 Ffarmworkers march and the proposals in the U.S. Senate to create the César Chávez and Farmworker National Park along our route.

César Chávez, American

“Each time a community changes a street name, adds a new class to the curriculum, or publishes in a new language, they are making a statement about who belongs.”

Meeting up at the Capitol building with Hector Amezcua, a visual journalist with the Sacramento Bee newspaper, we learned about his career in journalism, and his experiences as one of the first Americans to get a college degree in Chicano/a studies.

Our next destination was the Sacramento/San Joaquin River Delta, a winding maze of levee roads that were once home to Native Americans who fished and farmed along the shifting waterways. Indigenous people were forced out of the area just before the 1848 Gold Rush, and the levees and farms followed soon after. Fueled by the breakfast sandwiches provided by Hector, we stopped for a coffee in Isleton as the city prepared for its upcoming annual attraction—the Delta Crawdad Festival that brings in thousands of tourists from across California.

Even as we rode along the levees, politicians in Sacramento were debating whether to dig a controversial tunnel under the Delta to increase the water supply to Central Valley agriculture.

Gale force winds on our final day made the bridge to San Francisco’s East Bay impassable for bicycles. We recalibrated, turned north and rode through the surreal landscape of turbines at the Shiloh Wind farm, which combines pastoral scenes of grazing livestock with the new industrial economy of wind power

We fought brutal headwinds as we headed west, and finished our ride in Freeport, 553 miles from our start in Bakersfield, just in time to catch a series of Amtrak trains and commuter rail lines, flying south through the industrial landscapes of the East Bay.

Journey's end

A pile of Ivan Sigal's equipment at the end of the ride: luggage, saddle, lights, spare tubes, tools, helmets, bags, sunscreen, wallet, utility spork, and bicycle helmet. Photo by Ivan Sigal (CC BY 4.0)

As we unpacked our bikes back in the Bay Area, I revisited the reasons we set out on this ride. “Thanks for getting me back into the world after COVID,” Ivan told me, as he sorted photographs for his upcoming art project.

I also thought about all the people we met and the future they are creating for their children in the Central Valley. I'm grateful for the chance to tell some of their stories and raise funds for community organizations that are leading the future. Ivan and I plan to publish more stories about our ride in other publications in the coming months.

Supporting Environmental Justice and Indigenous Language Communities

Our ride is raising funds to support future leaders in the Central Valley and beyond. Please consider donating:

- The Central California Environmental Justice Network supports grassroots leadership in rural communities of color to promote environmental health education, community organizing, and citizen science

- Rising Voices supports marginalized and indigenous language communities to tell their own stories, on their own terms

Acknowledgments:

We are so grateful to everyone who supported this ride to happen, including our partners, family, and friends. We are especially grateful to Georgia Popplewell here at Global Voices, for leadership on fundraising systems, publishing, editing, video production, and social media, and also to:

- Adem, for loaning Ivan a bicycle after his was hit by a car

- Georgia, for countless support, including editing and video production

- Ian, for loaning Nathan an indoor trainer when California’s weather was crazy

- Pablo, for advice on the route and storytelling

- Nayamin, for ideas, introductions, and collaboration

- Monica, David, and many others, for connections to Central Valley leaders

- Jean and Maisha, for leads on Black history in the Central Valley

- Dave and Margaret, for introductions to people involved in the 1966 Farmworker March

- Marshall, for a great conversation about the farmworker march, research and storytelling

- Willow and Reed, for connecting us to California cycling communities

- Paul, for advice on slow journalism

- Cameron, for photos

- Rohini, for encouragement and laddu for the road

- The wonderful community of scholars at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, who encouraged the ride and cheered us on

Post a Comment