How authorities promoted surveillance, self-censorship, and laws restricting rights

Originally published on Global Voices

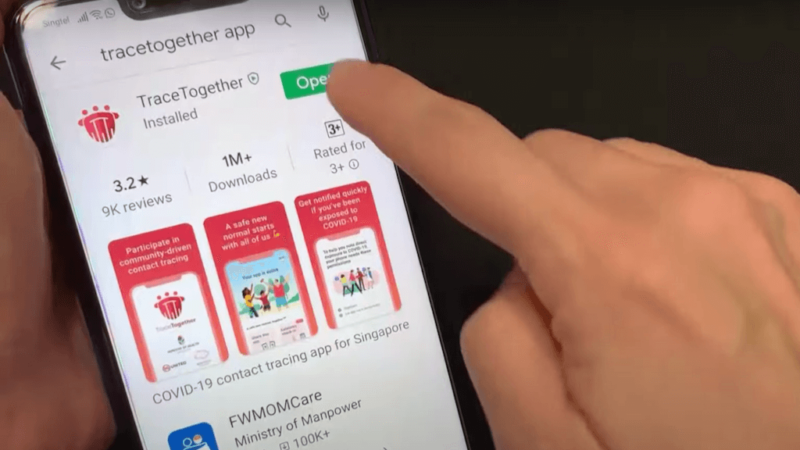

The Singapore government rolled out the TraceTogether app for its contact tracing initiative. Screenshot from GovSG video. Photo from EngageMedia

This edited article by Dr. James Gomez was originally published by EngageMedia, a non-profit media, technology, and culture organization, and an edited version is republished here as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices. This is part of a series that focuses on the lasting impact of the COVID-19 crisis on digital rights and tells the continuing story of digital authoritarianism in the Asia Pacific.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Singapore government strongly pushed forward its use of surveillance technology. The government promoted tracking applications and other monitoring tools as a leading solution to the health crisis. This article argues that the government used COVID-19 to legitimise the extension of surveillance infrastructure. Using health risk concerns, the government was able to — without facing any resistance — get its citizens under the ambit of digital authoritarianism.

The consolidation of state surveillance

Even before the pandemic, Singapore was moving towards being a surveillance state, devoting a significant amount of its resources to improving its monitoring capability. As of May 2023, there were a little over 109,000 CCTV cameras in the city-state, which amounts to nearly 18 cameras per 1,000 people. The island also has at least 20,000 public Wireless@SG hotspots. Wireless@SG is operated by internet service providers (ISPs), which are majority-owned by the government. These ISPs have been reported to give away personal information of their users to the government.

Apart from these tools, which provide lawful mechanisms for obtaining information and data from people living in the country, the Singapore government has acquired and used state-of-the-art spyware against critics of the ruling People's Action Party administration. The country’s law enforcement agencies have “extensive networks for gathering information and conducting surveillance and highly sophisticated capabilities to monitor […] digital communications intended to remain private.” These capacities were utilised against government critics and political activists, as revealed by reports and leaked documents. For example, in 2021, the government reportedly attempted to use spyware to hack into the Facebook accounts of two Singaporean journalists whose pieces are often critical of the government.

The use of surveillance tools, whether their use is legal or not, is enabled or facilitated through legal provisions and loopholes. At the government’s disposal are the Cybersecurity Act, Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, and the Infectious Disease Act. They contain vague and subjective definitions of key terms. To name one example, the High Court, in the case, Chee Siok Chin and Others v Minister for Home Affairs and Another, laid out the context of “public order” in which rights may be restricted. The High Court’s interpretation, however, is built upon what is considered the ‘interest’ of public interest and not the maintenance of public order. This gives room for the government to implement intrusive measures against individuals even though such measures may not contribute to the maintenance of public order.

Online state surveillance

Throughout the course of the pandemic, surveillance technology played a crucial role in Singapore’s COVID-19 measures. The government concentrated on subduing the infection rate to the bare minimum by restricting and controlling people’s movement. This was made possible by tracking applications. Applications developed by the government, SafeEntry and TraceTogether, later merged into one under TraceTogether.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the use of tracking applications raised questions from the public, who were particularly concerned by the infringement of their privacy. Many people feared that the applications would give away their geo-location and movement, enabling the government to assess their habits and activities. Some were concerned that the government might eavesdrop on phone conversations through these apps. There were fears of the applications being the government’s Trojan horse for spyware to be embedded in their devices. Such concerns were not groundless, given Singapore’s history of state surveillance combined with vague and excessive cyber laws and legal loopholes.

However, the government was quick to dismiss such concerns, arguing that TraceTogether operates on Bluetooth technology and uses a “digital handshake” to collect data only when a device comes into proximity with other devices. It does not use GPS technology, which can pinpoint the real-world location of devices, nor does it collect real-time movements.

Such explanations are problematic because they are built on the assumption that Bluetooth technology is privacy-friendly. This has been proven wrong as one study showed that TraceTogether can identify and locate its user. The Bluetooth technology itself, while less intrusive, offers little to block the government from accessing data or hacking the handset. By downplaying the intrusiveness of the application, the government was able to set a new standard of what was publicly accepted when it comes to surveillance. Moreover, it omitted from the public discussion concerns regarding legal loopholes and overbroad laws that legalise mass surveillance in the first place.

Normalisation of surveillance as part of life

The Singaporean government used the rhetoric of the common good to compromise on rights to privacy, citing health and safety as reasons for enforcing the tracking application. The argument goes that it is the duty of good civilians to sacrifice some of their rights for the collective good of their fellow nationals. The government even used healthcare workers to support this claim, saying that the application will lighten the burden of healthcare workers who risk their lives for others.

As the pandemic was prolonged, surveys show that Singaporeans became more in favour of TraceTogether as a solution to the health crisis. This proves that many Singaporeans have been successfully led to believe in the government’s use of security as a justification for extensive surveillance. The enforcement of TraceTogether normalised the state of being under surveillance and made it an acceptable part of life in Singapore.

The government took advantage of Singaporeans’ indifference and trust and expanded its physical and online surveillance networks, both legal and illicit. In February 2022, it came to light that the Singaporean government purchased spyware from QuaDream, an Israeli developer. Soon after that, also in February 2022, the chairperson of the opposition Workers’ Party claimed in parliament that she had received a notification from Apple that the government attempted to install spyware into her cellphone.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, the Singapore government has continually used this momentum and the public’s acceptance to expand their surveillance. Facial recognition has recently been introduced in public services, including the use of SingPass – an application all citizens and residents can use to access government services. The SingPass application now incorporates facial recognition technologies, which, according to the official reasoning, will facilitate easier access to both government and private services.

Overall, surveillance has reinforced a culture of self-censorship and fear in Singapore which further mutes public criticism of the government. Citizens and residents of Singapore who live under intensive surveillance are becoming more subconsciously fearful of speaking up and being more mindful of their actions both on and offline.

Constant surveillance in Singapore also creates unease among its residents. People may fear that any wrong actions or choice of words could be reported back to the government. Such unease can be further exacerbated by lateral surveillance – a form of surveillance conducted by individual members of society.

The pandemic normalised digital authoritarianism in Singapore. As the pandemic lingered, Singaporeans have become more and more accepting of the fact that being watched by the government via their electronic devices and other forms of surveillance was in their best interest. Such acceptance was brought about by the government’s use of the rhetoric of the common good, which forces Singaporeans and residents of Singapore to voluntarily give up their rights to privacy as a form of patriotism. As a result, the pandemic shaped the city-state’s’ favourable attitude and mindset toward state surveillance.

*Dr. James Gomez is regional director at the Asia Centre. He oversees its evidence-based research on issues affecting the Southeast Asian region.

Post a Comment