‘I decided to shift from being a translator to becoming a writer myself’

Originally published on Global Voices

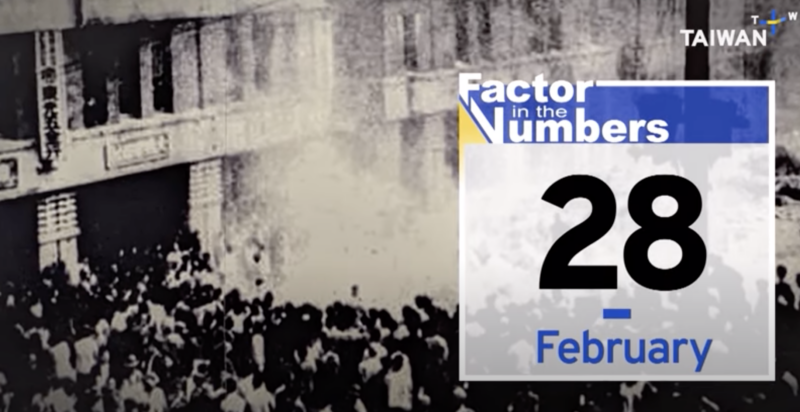

Screenshot from Taiwan Talks YouTube channel explaining the consequences of the White Terror on Taiwan.

Translations into English of non-anglophone world literature occupy a tiny space on the international book market. For certain global writers, one way to circumvent this enduring obstacle is to switch to writing in English. Global Voices spoke to a Taiwanese author and literary activist who made this choice to make her voice heard more widely.

Chieh-Jane Anderson-Wu (吳介禎) is a Taiwanese writer who has published two collections about Taiwan's military dictatorship (1949–1987), known as the White Terror: “Impossible to Swallow” (2017) and “The Surveillance” (2020). Currently she is working on her third book “Endangered Youth—to Hong Kong.” Her short stories have been shortlisted for a number of international literary awards, including the Art of Unity Creative Award by the International Human Rights Art Festival. She also won the Strands Lit International Flash Fiction Competition, and the Invisible City Blurred Genre Literature Competition.

The interview took place over email after long conversations in Taipei, and has been edited for style and brevity.

Portrait of C. J. Anderson-Wu. Photo used with permission

Filip Noubel (FN): You write short prose and poetry in English, yet you grew up speaking Taiwanese and Mandarin Chinese. How did you make this decision?

C. J. Anderson-Wu (CJAW): I have been working as a translator of of literature and texts focusing on art and architecture throughout my career. How to bridge the communication gap between people from diverse cultural backgrounds is thus always on my mind. Today in Taiwan, visual arts, theater, and architecture experience few obstacles to connecting with international partners and audiences. However, literary works often prove to be much more challenging to interpret.

The lifting of censorship on publications in 1991 marked a remarkable turning point for literary creation in Taiwan. Writers immediately embarked on a journey of seeking to compensate for what was lost during the oppressive era under martial law. With admirable artistry, they tackled complex historical, social, and political issues in their works. It has been a long process for our society to restore our identity and rectify the false national narrative that was forcefully imposed on the public through propaganda. In this pursuit of unspeakable truths, delayed justice, and redemption, Taiwan's contemporary literature plays a significant role.

I have personally helped publish several books featuring highly acclaimed Taiwanese writers. Through the feedback received from readers of Taiwanese literature in translation, I have come to understand the immense difficulty in effectively conveying these profound issues to international readers solely through English translations. It was during this realization that I decided to shift from being a translator to becoming a writer myself, although I continue to work on translating Indigenous and Taiwanese-language poets.

My decades of experience of translating has greatly nourished my writing, but instead of venturing into writing fiction or poetry in Chinese, I chose to be a humble reader of Taiwanese writers who explore themes such as human rights, state violence, and historical traumas in Chinese, Taiwanese, Hakka, and Indigenous languages of Taiwan.

Cover of C.J. Anderson-Wu's book The Surveillance. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

FN: Part of your prose focuses on the White Terror, a part of Taiwan’s history that is little known outside the island. Does writing in English play a role in your creative and activistic strategy?

CJAW: Indeed. Taiwan experienced the implementation of martial law from 1949 to 1987, and it was not until 1991 that the Statutes for Detection and Eradication of Espionage were finally abolished. This period was marked by severe censorship, the banning of publications and public speeches, widespread surveillance, and the persecution of writers and readers of banned books. Political dissidents and their families faced relentless hostility, and anyone opposing the government was often labeled as a national traitor and purged. The impact of this era continues to shape Taiwan today. This authoritarian period can be compared to what South Korea, Spain, Chile, and Argentina also experienced. Today the task of achieving transitional justice in Taiwan remains unfinished.

Moreover, the political oppression that was experienced in Taiwan is now occurring in Hong Kong. The imposition of the 2020 National Security Law has resulted in the exile or imprisonment of pro-democracy activists, effectively silencing the entire society. Sadly, many liberals in the Western world have chosen to turn a blind eye to the grave human rights violations in Hong Kong, excusing themselves by claiming they don't want to intervene in China's “domestic affairs.”

After publishing two collections of stories about the White Terror in Taiwan, I made a concerted effort to write and publish prose and poetry that focus on the plight of Hong Kong. The injustice occurring with freedom activists in Hong Kong should never be overlooked, and the risks they have taken for their fights should never go unacknowledged by a broader readership.

FN: Several Sinophone writers who live outside their mother tongue society write in English or other languages: Ha Jin, Xiaolu Guo, Dai Sijie. In your view, is it an issue of the audience? Linguistic distance that gives freedom? Other factors?

CJAW: Absolutely. Given that only three percent of publications in the US are translated works (about five percent in the

UK), writing in English is the best strategy for both the authors and the publishing houses to reach out to a greater audience. I would say that when it comes to how authors incorporate a foreign language in their writing, everyone has different approaches. Personally, I post more intimate things in Chinese on my social media pages to share with my community, and submit stories or poems in English to journals in the US, the UK, India, Ireland, Australia, and other English speaking societies to express my political opinions. English enables me to be more outspoken, considering it’s a competition in the world of dominant cultures.

FN: You leave Chinese and pick English. Most indigenous authors of Taiwan pick Chinese to write about their identity, culture and society. You work at Taiwan Indigenous PEN and know many indigenous authors: how do you see this process of appropriation of Chinese as a literary means by people who come originally from a different culture?

CJAW: Native American poet laureate Joy Harjo uses the term “Enemy’s Language” to refer to English for Indigenous writers who have to write in the language of their colonizers, due to the cruel assimilation and the long loss of their tribal languages.

Similarly, Indigenous writers in Taiwan had endured suppression under the Qing dynasty and the Japanese colonial rulers (1895–1945), as well as the exploitation of the nationalist [or Kuomintang] government. Writers from older generations struggled between their mother tongue, and the official language, Japanese, and later with Mandarin Chinese that was enforced by the nationalist government.

Younger writers, whose life experiences are mainly in urban, often have to reconnect to their tribal languages during their occasional returns to their tribal communities, and learn from their elders. This awareness of “the sunset of culture” pointed out by Paelabang Danapan (a.k.a 孫大川 or Sun Ta-Chuan ), one of the pioneers of Taiwan’s Indigenous Rights Movement, echoes Joy Harjo’s sentiment about the inevitable decline of Indigenous cultures. Nevertheless, many of them are still striving to restore their traditions and identities. As Paelabang Danapan said, “Literature is the guardian of our ethnic assets,” and although many of them are writing in Chinese, they developed all kinds of strategies to intervene in this dominant language to remind readers that their perspectives stem from very different cultures and worldviews.

As the world is faced with environmental crises, hopefully Indigenous voices will be heard. I am profoundly blessed by Taiwan’s Indigenous literature, as it has broadened my horizon by delivering precious knowledge about nature, life, and the value of being a human.

Post a Comment