Dhaka is sinking and its groundwater resources are running out

Originally published on Global Voices

Illustration via Unbias The News. Used with permission.

This article was originally written by Shamsuddin Illius and published in Unbias The News as part of the “Sinking Cities” series. An edited version is republished in two parts by Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement. Here is the first part.

With homes swallowed by floodwaters and river erosion, many migrants from all over Bangladesh have opted to move to the cities of Dhaka and Chittagong for ‘safer ground.’ But these options for ‘safer’ ground are also sinking.

Every morning, Abdul Aziz wakes up before dawn in a 100-square-foot shack he shares with his wife and two daughters. Pedalling rickshaws in the streets of Dhaka is the only way the 50-year-old can provide food for his family now.

Aziz lives in the Korail slum, the largest slum in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. The slum is home to nearly 200,000 people, most of them climate migrants.

Once a farmer by profession, he used to live in Sylhet, the northeastern part of Bangladesh, where he planted rice and raised cattle on an acre of land. But a sudden flash flood and water congestion in May 2022 left him, along with over 4.3 million others, homeless. The floods washed away his entire property, including four cattle. Having no place to live and no means to earn a living, he ended up in the Korail slum in Banani.

The slum is overcrowded and squalid, with poor sanitation, water, and drainage. The average slum house is around 100 square feet in size and consists of just one room. Slum dwellers’ houses are made with flimsy bamboo frames and corrugated iron roofs, which amplify the sweltering heat and leave them vulnerable to storms. Overcrowded slums with illegal gas and electric utility lines pose major fire hazards. Slum dwellers confront considerable health hazards as a result of their high density and poor access to healthcare, which frequently has a detrimental influence on their livelihoods.

While cyclones uproot 110,000 people each year, an average of a million people are displaced in Bangladesh due to flooding, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. In addition, two-thirds of the country is less than 15 feet above sea level, making sea-level rise an increasing threat.

“Losing home and livelihood and searching alternatives, every day 2,000 people move to Dhaka, 70 percent of them due to natural disasters and climate change. The city is struggling to cope with the pressure of the migrants,” said Atikul Islam, mayor of Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC), the site of the largest Korail slum, in an interview with Unbias the News.

Chittagong city, meanwhile, has been projected to experience a high rate of internal migration along with the district of Khulna, covering an estimated 15,000–30,000 migrants due to increasing soil salinity from sea-level rise. The 5,000 slums in Dhaka are home to four million people, while Chittagong’s 200 slums house 1.4 million migrants.

Why Dhaka is sinking

Aziz and Begum tried to move to what they deemed as safer ground. However, Dhaka is already suffering from land subsidence.

Dhaka, the fastest-growing megacity in the world, is home to more than 20 million people, with over 48,000 people per kilometre, and is itself facing a climate crisis. On top of this, groundwater levels are slowly depleting due to excessive extraction and inadequate infrastructure. The city is almost entirely dependent on groundwater resources as the freshwater sources are often unusable. The river basin area of Dhaka is linked to the Ganges-Brahmaputra river basin system (locally called the Padma-Jamuna-Meghna river basin system). The water of Dhaka's river is unusable because of industrial pollution. In addition, officials mismanaged the old distribution system from the water treatment plants. Residents often complain that the water coming out of the taps stinks and is often muddy because the water pipes have eroded with age.

Saleemul Huq, climate scientist and director of Dhaka-based research organization International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD), said that Dhaka is sinking for two main reasons — excessive groundwater extraction for its booming population and decreasing wetlands as a consequence of infrastructure development and rapid urbanization. Huq said:

The wetlands that used to be part of the areas of Dhaka have shrunk considerably over the last 20–30 years. As a result, the water used to recharge the groundwater is no longer recharging groundwater. This increases the subsidence rate of the city.

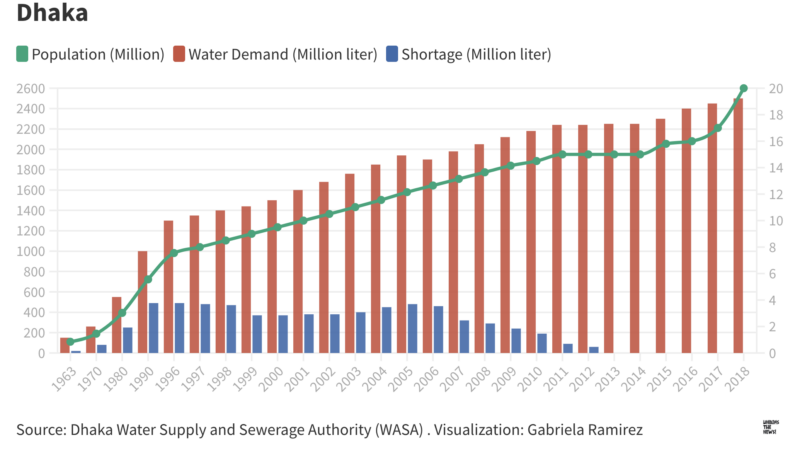

Data from the Dhaka Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (DWASA) shows that dating back to 1963, when the population of Dhaka was less than a million, the demand for water was 150 million litres per day, which is enough to fill about 60 Olympic-sized swimming pools. The DWASA would supply 130 million litres (MLD) by extracting groundwater using 30 deep tube wells (DTWs). At that time, they did not have any water treatment plants.

In 2021, the population of Dhaka ballooned to 20 million, and so did its water demand. Dhaka now provides 2,590 MLD per day to citizens by extracting groundwater using 906 deep tube wells, along with five water treatment plants. But this provision is still slightly lower than the demand of around 2,600 MLD, and leaves some without enough fresh water.

Aside from the DWASA’s 906 DTWs, about 4,000 households also get water from their own deep tube wells. But this groundwater extraction has contributed to the depletion of the water level in Dhaka. In 1960, water was usually found at a depth of 20–30 meters. According to DWASA Managing Director, Taqsem A. Khan, people now need to reach an extraction depth of 400–750 meters at places for DTWs to draw water. Khan explained that 66 percent of Dhaka’s water is taken from underground aquifers. The rest comes from surface water, such as rivers and other above-ground bodies of water, as explained by National Geographic. “We have to go over 700 feet for getting water, [a level] which is increasing every year.”

Anwar Zahid, who heads the Directorate of Groundwater Hydrology at the Bangladesh Water Development Board, warned that the water level of Dhaka has dropped alarmingly in the last couple of decades. “The groundwater level in Dhaka city areas is decreasing very sharply with annual decline rates of 1.5 meters every year to 2.11 meters every year,” he said. Mongabay reported in August 2022 that groundwater levels in the greater Dhaka area could drop by 2030 by 3–5.1 meters (9.8–16.7 feet) per year, citing a study by the Bangladesh Water Partnership, a global network working on water security issues.

Syed Humayun Akhter, a geologist and vice-chancellor of Bangladesh Open University, said if the underground water extraction proceeds at an unsustainable rate, Dhaka will continue to sink, with some parts of it suffering subsidence at varying scales and intensity.

The search for alternatives

To reduce the dependency on underground water, DWASA has launched several projects for surface water treatment. “Finding alternatives, we have taken a decision. We have to go for 70 percent surface water and 30 percent underground water. If we can do it, Dhaka city will be environmentally viable and ecologically stable. Then we would have started our journey,” DWASA Managing Director Engineer Taqsem A. Khan said, “We had to get water from the Padma River, which is 22–32 km away from the capital Dhaka.”

In order to meet the demands of this bustling population and replace the underground water with a surface water treatment plant, WASA (Water Supply and Sewerage Authority) has to take a huge soft loan from different development partners, such as the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, JICA, the Chinese Exim Bank, the Korean Exim Bank, and the German Development Bank.

“Climate change is weighing extra pressure on the budget of Bangladesh. To implement the projects relevant to face the threats of climate change adaptation, we are spending money from our own resources and also borrowing money from foreign lenders,” Md. Shahab Uddin, minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, said in an interview with Unbias the News.

Post a Comment