GotaGoGama did not just provide a springboard to oust a president

Originally published on Global Voices

This article by Pranith Wirasinha was originally published in Groundviews, an award-winning citizen media website. An edited version is published here as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices.

GotaGoGama is gone. Gota has returned.

Things have regressed in the past five months or so. The nucleus of Sri Lanka’s popular protests has ceased to exist. Its last days were a shadow of what it once was. The last batch of protesters who occupied the skeleton structures that made up the remnants of GotaGoGama was still resilient. One protester held firm in the belief that if the same crowds that gathered on July 9 had come to support GotaGoGama in early August, it would have made it through and continued its struggle. Unfortunately, though, the general public’s silence was deafening. Disillusioning was the idea of having a makeshift settlement of “vagrants and homeless” people opposite the now full car park at Kingsbury hotel.

Read our special coverage: Sri Lanka in Crisis

International Literacy Day is a day that is usually celebrated in Sri Lanka. This is a country that can lay claim to an extremely high rate of literacy. But what could literacy truly show in a country that is reeling from an economic crisis of the scale we are currently experiencing? What could lay claim to the extreme dearth in political literacy that sees large swathes of the public place their vote for those that have not even completed their secondary education? Or an inability for elected representatives to rectify or recognize years of systemic and structural issues that have both morally and economically bankrupted this country? Literacy in its most basic definition is the ability to read and write but what good is that when what is read and written is not used to improve or educate? What good is literacy if it isn’t for learning, communicating and advancing in search of basic human development?

This idea of not just learning but immersive learning was one that was central to the Aragalaya protests. GotaGoGama did not just provide a springboard to oust a president entrenched by authoritarian power but inculcated and encouraged the people who engaged with or even just visited GotaGoGama to understand and contextualize the predicament the country was in, and, indeed, has been since independence, around the setting and purpose of the protest site.

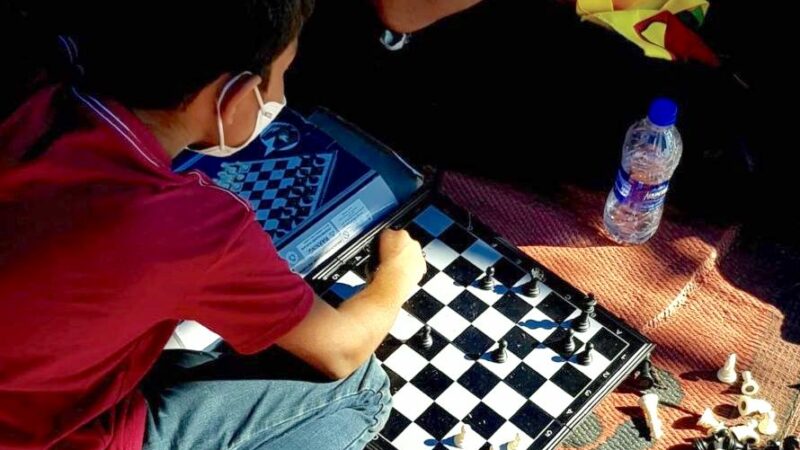

Debates and discussions were the norms, as was artistic expression. Reading books is sometimes seen as a thing of the past, a habit that many of today’s generation don’t have the patience to delve into, but GotaGoGama’s library was very much the heart of the little village — set up in the early days of the #OccupyGalleFace movement and extending to the final days of the struggle at Galle Face. The library came into being through a collective effort of volunteers and protesters. When the presidential secretariat was occupied by the protesters, its lobby housed books that were literally passed on from the GotaGoGama library through a human chain. It was a symbolic moment in the context of the Aragalaya, one that emphasized and positioned learning and knowledge at the centre of the people’s struggle. It encompassed a sort of political awakening among Sri Lankans not just as people of the country but as citizens of the country. Their mandate is not through just the vote at an election but as a stakeholder in a political contract.

GotaGoGama offered not just an education in political science, economics, human rights and history but also on concepts such as communication and acceptance, all marked by an immersive experience, an essential in any educational space.

As much as literary education through the library was an important part of all this, there were also steps taken to inculcate and encourage citizens to think critically and engage through film education. GotaGoGama’s TearGas cinema regularly featured timeless classics and locally produced short films and documentaries. For many, this was their first experience seeing a film on a big screen, the first time cinema was thought-provoking and challenging rather than commercial. It was, indeed, a sight to behold how the cinema even on a rainy night drew in scores of viewers who questioned superstition and its ability to continuously dupe the population. Filmmaker Nayomi Apsara, in a conversation with Groundviews, spoke of how the medium offered a new way to question the issues that tore away at the core of our country to people who had never objectively viewed these questions.

None of this is to say that GotaGoGama was perfect and without its ideological shortcomings and flaws. From Aragalaya’s lack of clarity underscored by the theme of the adare aragalaya (“the struggle of love”), which showcased solidarity with the armed forces, to the sometimes over-eager and tokenistic stances of unity, GotaGoGama lacked a cohesive identity that could have been said to have shed the bad while upholding the good. Yet it engaged, it provoked, it communicated and it allowed these ideas to mingle and marinate and take hold of people’s minds. Sri Lankans, as has been written and spoken about, have a habit of forgetting. It was a talking point that accompanied the return of Gotabaya Rajapaksa back into the country. It even perhaps underscores the educational deficiencies our system has inculcated within us where an education consists of at best paraphrasing what has been memorized as a sign of learning, only to subsequently forget its use as an exam that has tested the purpose of that piece of knowledge.

There is even a poetic quality to how, before the return of the ousted former president, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna political party, under the auspices of its future face, launched the Political Leadership Academy to “empower politically conscious citizens with better knowledge and skills.”

There lies the test for Sri Lanka now, a month after GotaGoGama came to a close. It begs the question of how its ideas have taken root in the minds of the thousands who engaged with this space of learning and how much thinking has been done about this learning. It is an important question to ponder when we celebrate an over 90 percent literacy rate. How has the ability to engage with learning (through reading and writing primarily) affected our view on committing to the country we would like to see at the end of this tunnel?

Post a Comment