Five literary books tagged by authorities as “subversive”

Originally published on Global Voices

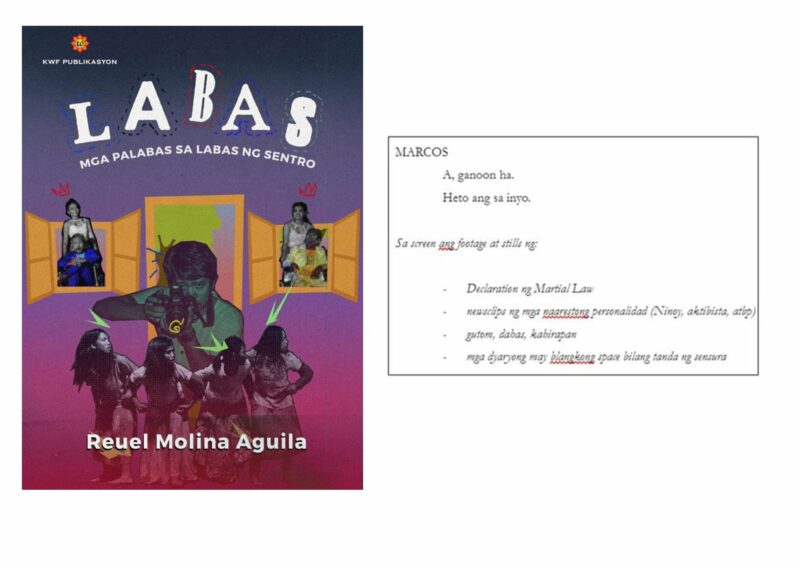

The five books tagged as ‘subversive’ by some commissioners of the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (Commission on Filipino Languages). Photo from Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility.

A government order stopping the publication and distribution of five books dubbed by Philippine authorities as “subversive” has been rescinded after a strong pushback by the Filipino literary and academic community against book censorship and repression.

The Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino [Commission on Filipino Languages] or KWF, a government agency under the Office of the President charged with promoting, preserving, and developing the country’s languages, withdrew its earlier order after sustained protests by the country’s leading academics and writers.

The Commission ordered the banning of the following titles in Memorandum 2022-0663 on August 9, after a talk show in far-right mouthpiece Sonshine Media Network International (SMNI) accused the books of “subversion” and red-tagged the authors as “communists”:

- “Teatro Politikal Dos” [Political Theatre Two] by Malou Jacob;

- “Kalatas: Mga Kwentong Bayan at Kwentong Buhay” [Letters: People’s Narratives and Life Stories] by Rommel B. Rodriguez;

- “Tawid-diwa sa Pananagisag ni Bienvenido Lumbera: Ang Bayan, ang Manunulat, at ang Magasing Sagisag sa Imahinatibong Yugto ng Batas Militar 1975-1979″ [Imparting the Meaning of Bienvenido Lumbera’s Writings: The People, the Writer, and the Magazine Sagisag in the Imaginative Stage of Martial Law 1975-1979] by Dexter B. Cayanes;

- “May Hadlang ang Umaga” [The Morning is Hindered] by Don Pagusara; and

- “Labas: Mga Palabas sa Labas ng Sentro” [Outside: Performances from Beyond the Center] by Reuel M. Aguila.

Red-tagging is a term used in the Philippines referring to the practice of branding individuals as terrorists or communist rebels “without substantial proof of any unlawful conduct.”

KWF Commissioner for Programs and Projects Carmelita Abdurahman and Commissioner for Operations and Finance Benjamin Mendillo penned the memo, which was also signed by three other KWF commissioners.

As the country commemorates Buwan ng Wika, the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino has issued a memorandum calling on schools and libraries to pull out the following

“subversive” books for being “anti-government.” @PhilippineStar @onenewsph pic.twitter.com/tCfhqkLJOj— Marc Jayson Cayabyab (@mjaysoncayabyab) August 11, 2022

“Subversive” books?

In the SMNI program “Laban Kasama ang Bayan” [Fight with the Nation], Lorraine Badoy, former communications undersecretary during the Rodrigo Duterte administration, and other anti-communist spokespeople, pinpointed particular words, dialogue, and even reference entries found in the 5 books that they condemned as “terroristic.”

Screenshot of footage from August 9, 2022 SMNI program labelling five Filipino books as subversive.

The anti-communist spokespeople highlighted lines from award-winning Filipino playwright Malou Jacob’s play Teatro Political Dos, a collection of 5 plays. These lines simply describe the EDSA people power uprising that overthrew the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in February 1986 as “the best thing that happened after fifteen years of Martial Law.”

Screenshot of footage from August 9, 2022 SMNI program labelling five Filipino books as subversive.

Also highlighted are lines from Filipino fictionist and literature professor Rommel Rodriguez’s “Kalatas,” a collection of vignettes and reflections. The text simply mentions the Philippine realities of some Filipinos organizing armed revolution against the government: “May umakyat ng bundok upang humawak ng Sandata” [There are those who leave for the mountains to take up arms].

Screenshot of footage from August 9, 2022 SMNI program labelling five Filipino books as subversive.

Scholar Dexter Cayanes’s “Tawid-diwa sa Pananagisag ni Bienvenido Lumbera,” a published thesis on the late Lumbera, a Philippine National Artist for Literature, is meanwhile singled-out for merely citing works by communist rebel leaders Jose Ma Sison and Julieta de Lima. Even reference entries of Marxist art critic Alice Guillermo and other academic works such as “Marxism and Literary History” were presented as proof of subversion.

Screenshot of footage from August 9, 2022 SMNI program labelling five Filipino books as subversive.

Dialogue from Don Pagusara’s stage-play “May Hadlang ang Umaga” depicting the historical circumstance of ordinary Filipinos talking about joining the armed struggle against the dictatorship is also tagged as already subversive in-itself. Pagusara is a multi-awarded playwright and poet writing in the Cebuano language and a former political detainee during the dictatorship years.

Screenshot of footage from August 9, 2022 SMNI program labelling five Filipino books as subversive.

The mere showing of social realities of the arrests of activists, hunger, violence, and poverty (“gutom, dahas, kahirapan”) during the martial law era in the setting of one of award-winning playwright and professor Reuel Aguila’s plays in the book “Labas” is also offered as proof of terrorism.

Authors speak out

In response to these accusations, the five authors penned a joint statement written in Filipino calling for the retraction of the false claims against them. The authors asserted that it was in fact the anti-communist spokespeople's attempts at red-tagging their writings as the real act of terrorism sowing fear among the literary and academic community:

Naniwala kaming hindi nabasa mismo ng mga nagpaparatang ang kabuuan ng lima naming libro. Naniniwala kaming isang uri ng karahasan ang pigilang maipakita ang iba’t ibang danas ng mga Pilipino. Naniniwala kaming isang uri ng terorismo ang magtakda kung ano lamang ang maaaring isulat at paano isulat ang mga ito.

We believe that the accusers have not read our books in entirety. We believe that stopping the showing of the diversity of the Filipino experience is a form of violence. We believe it is a form of terrorism to dictate what can be written and how to write it.

Rodriguez emphasized that “Kalatas” and his other literary works aimed to tell the truth about the realities of people taking up arms rather than encourage readers to fight government:

They were taken out of context because after all, it is so easy to say they are subversive because they contained such words. Am I the only one who used ‘revolution’ and ‘weapon’? No. Many people in history have used them.

Pagusara said that the censorship of their works brings about a chilling effect among the wider community of writers, artists, cultural workers, academics, and scholars. He explained that “May Hadlang ang Umaga” is based on his real-life experiences as an activist and political prisoner during Marcos’s martial law regime:

May Hadlang ang Umaga is a fictional play written in the 1980s based on the life of political prisoners held in custody at the Youth Rehabilitation Center, a former maximum security prison at Fort Bonifacio in Taguig City. It was actually archived in my mini library when KWF Chairman Arthur Casanova offered that the book be published.

KWF Chairperson Arthur Casanova, who was pressed to resign for allegedly allowing the publication of the books in question, denied the accusations in a statement. The official asserted that the five books in fact underwent the commission's regular review process for publication, saying the contents of the books all fall within the bounds of free expression and academic freedom.

Solidarity and pushback

A unity statement signed by over 30 cultural, educational, and language associations, organizations, and university departments expressed support for the beleaguered authors and their censored works. The statement asserts that books can cite even texts that are considered by the state as subversive or revolutionary:

Bahagi ng akademikong kalayaan ng mga manunulat, guro, mananaliksik at ng lahat ng mga mamamayan ang pagbabasa, pagsusuri, pagsipat, pag-cite, pagsangguni at paggamit sa KAHIT ANONG BABASAHIN, SINUMAN ANG SUMULAT AT SINUMAN ANG NAGLATHALA.

The academic freedom of writers, teachers, researchers, and all citizens include writing, analyzing, investigating, citing, referencing, and using whatever writing, whoever authored and whoever wrote it.

The University of the Philippines’ Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature, where Aguila and Rodriguez are faculty members, pointed out the irony of the censorship of the five books written in the Filipino language during the country’s Buwan ng Wika [Language Month] and by the government commission tasked with promoting the national language no less.

The Congress of Teachers/Educators for Nationalism and Democracy (CONTEND), an organization of activist faculty and academic workers at the University of the Philippines, meanwhile contextualized the latest case of book censorship in the country's long history of red-tagging:

This incident cannot be divorced from other attacks on academic freedom in the past few years under the Duterte regime and attempts to distort history from the Marcos camp. We remember the purging of historical and political books tagged by the state as “subversive” from state university libraries, the red-tagging of certain bookstores, and the banning of websites and media outfits that cover the realities of the Filipino people.

On September 21, 2022, KWF Commissioners Alain Russ Dimzon, Angela Lorenzana and Hope Sabapan-Yu officially withdrew their signatures from Memorandum No. 2022-0663 through Resolution No. 27. The issuance of the new resolution came to light at a session of Philippine Congress, when activist lawmakers under the Makabayan (Pro-People) Coalition pressed the issue of book censorship during the hearing for the proposed 2023 budget of the KWF.

Alliance of Concerned Teachers Party's Congressional Representative France Castro said that this pushback against book censorship “would not have been done if not for the clamor of the people and strong condemnation of the people against attacks on academic freedom, freedom of the press, and free speech.”

Disclosure: The author teaches at the University of the Philippines Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature. He is also a member of the Congress of Teachers/Educators for Nationalism and Democracy.

Post a Comment