The economic crisis is weighing heavily on Sri Lankan women

Originally published on Global Voices

The Samathai Drummers for Justice from Batticaloa perform at the gates of the Presidential Secretariat in Colombo. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

This post originally appeared in Groundviews, an award-winning citizen media website in Sri Lanka. An edited version is published here as part of a content-sharing agreement with Global Voices.

In late April, women from movements and collectives in the north and east of Sri Lanka marched into the GotaGoGama (“Gota Go Home”) occupation village at Galle Face in Colombo to express their concerns and issues in solidarity with the struggle in the south. From organizing satyagrahas (civil resistance) on the streets against a plethora of issues to engaging with women-headed households on solutions to overcome the economic crisis, women’s collectives have been playing a defining role within the delicate social fabric and local economies of communities in the north and east.

The Samathai Drummers for Justice from Batticaloa up close. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

The hardships these women have had to contend with daily have created the resourcefulness to help keep their own communities going. Their presence at GotaGoGama was not a blanket statement against the use of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) to detain family members after the Easter Sunday attacks of April 21, 2019 or the urgent need for justice and accountability after the civil war that has seemed elusive for more than a decade.

These concerns were certainly communicated, but like the thousands of others at GotaGoGama, the women's primary purpose was to show their displeasure at the economic conditions that had pushed their communities, their people, and their livelihoods to the brink.

The women marched up to the gates of the Presidential Secretariat, very much the heart of the protest movement at GotaGoGama, at around 10.30 a.m. Here the Samathai Feminist Friends from Batticaloa performed with their parai drums. Speeches and chants from the ensemble echoed through; invocations of feminist activist Kamla Bhasin and the critiques of power hierarchies and patriarchal violence that have left their indelible marks on Sri Lanka’s history.

Women from the north and east march into GotaGoGama. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

‘We want the power of equality, justice and love. Not love for power.’

It was a powerful moment in the larger context of the protests at GotaGoGama. After their march to GotaGoGama, they continued onwards to the People’s Voices Tent where they set up camp for the day. Groundviews spoke to some of the women who had made the overnight trip from Batticaloa.

“This is very different for us. Previously we had ways to cope, we could manage because we always found solutions,” says Vanie Simon. “But the economic issues are heavily weighing on the women we are working with.”

Simon is a founding member of the Women's Action Network from Akkaraipattu. She tells us of how one of the most familiar things growing up in the East was hearing gunfire. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students (EROS), Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF), the Sri Lankan military, it didn't really matter. Nor did it make a difference.

Vanie Simon is a founding member of the Women's Action Network from Akkaraipattu. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

The sound of gunfire was a symbol that defined her childhood, she says. It was this constant recollection and harbinger of violence that empowered her to push back against a burgeoning ecosystem of militancy, war and violence that is held by years of systemic and structural discrimination. It is that which defined all her rights work in the most dangerous and demanding situations and environments.

Still.

Over 30 years of war and violence and it is the impact of the current crisis that has severely tested her:

In all the years of rights work I have done, this is a first. I’ve never had to fight on behalf of women who are hungry. We thought we were used to this situation and that there were alternatives we could find. We women ran a self-sufficient economy even during the war where we managed with what little we could produce. There was access to some sort of food, where we could keep afloat a basic local economy, but this is completely different.

Placards and Posters at the ‘People's Voices Tent’, GotaGoGama. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

Women's groups have been at the forefront of local economies in the east. During the COVID-19 outbreak, when trade had more or less come to a standstill, it was the women who revived age-old food strategies and cultures that had sustained communities through scarcity. It is the women that form the nucleus of the local economies there.

Anuradha Rajaratnam from the Suriya Women’s Development Centre tells us that the present crises and shortages were projected late last year following consultations with the community. They had a clear understanding of the internal and external pressures within the economy, especially during the pandemic. Being well versed in agriculture and food distribution, they had a grasp on how an already burdened economy was only about to be made worse by the banning of chemical fertilizer:

We knew it was going to happen so we gathered and we marched together last December alerting the government that we have this crisis at hand but nobody took any notice of us.

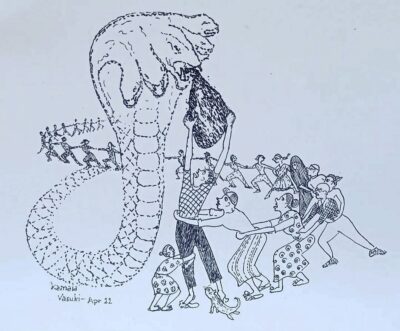

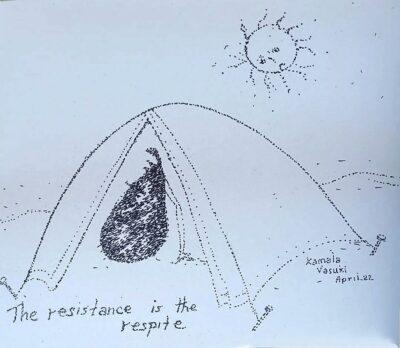

“It’s very important to be here and show our support to what’s happening but also to show our identities and our histories that have defined the struggles we’ve been having and the battles we have been fighting,” says Kamala Vasuki, artist and drummer for the Samathai Feminist Friends. Her cartoons adorn the tent that the group has settled into for the day.

At the heart of the Protest Site. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

The parai drum is a part of that history Kamala speaks of, one she embodies every time she beats it into a rhythm. The parai has been used historically to make announcements during special occasions. Its presence here as an instrument to mark special occasions bears significance too, as it is not an instrument often played by women, being a collective cultural symbol tainted by an age-old stigma and prejudice. It is the women that carry the burden of many of these issues but it is the women, too, that have provided the alternatives, she adds.

As feminist movements, the collectives found their advocacy and struggles against power relations. It’s something they're accustomed to seeing in numerous forms; from family disputes and domestic violence to the rude government officials and their disregard for a woman's agency within a community. The impact of power hierarchies is something that goes both ways, they flow down as much as they go up, tracing themselves all the way up to the executive presidency. Anuradha says:

Whoever comes into power, all that power cannot be with one person. The executive presidency needs to be abolished. At no level should it exist nor should power be centralized within one person. Power needs to be decentralized and everyone should share in the powers, that is the country we are looking for.

Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

We as feminists are trying to change these cultures and abolish these patriarchal structures. Women's voices need to be heard. Change should happen through women's representation; representation goes even beyond politics, beyond just saying that there is equality because it is the amendments and constitution. We have to witness it in our life. Women have been asking for this simple recognition and equality for a long time.

When asked what positive changes one can take from the protests at Galle Face, Vanie Simon recognizes that people here are for the first time holding the Rajapaksas accountable. For the most part, it is the economic crimes, maybe, but that is still some sort of accountability. “He was a person that was untouchable for so long. Now he is being held accountable by the majority, so we have some hope that some of our concerns and demands will be heard amidst all this, as well.”

Local politicians and government officials in the East have been guilty of taking over natural land for construction. Another major point of concern. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

It's a change that the collectives here could not have expected, nor indeed anyone in the north and east. A change nevertheless, that’s taken with a pinch of salt.“We feel like we have no say in GotaGoHome, to be honest, because we never asked him to come in the first place!” Kamala Vasuki says. Communities and family back home teased the group as they were heading to Colombo, she lets us know.

It is still too early to say if the protests at Galle Face will affect bringing changes that are needed in the north and east. Even if this marks the end of the Rajapaksa era in Sri Lanka, many of the injustices perpetrated and weaponized by the regime are systemic and deep-rooted. It's a system that's been historically against Sri Lanka's Tamil and Muslim communities.

It is very different here in Colombo. There is a lot of open anger and insults. People aren't afraid to voice these out even in front of the police and the military. If they get arrested, their lawyers appear in court on their behalf. We don't have that luxury.

Take, for example, what happened to opposition MP Shanikyan: a court order has been passed to prevent him from protesting. There is open intimidation in the north and east, so there is a big difference here and the places that we are in. There is a big difference in how the government and even the military are fearful of the people. They are very concerned and afraid of an uprising in the south. They don't care about that in the north and east. They don't even consider us as people who are protesting.”

Police keep watch on Anti-Government protesters opposite the protest site MynaGoGama, Temple Trees. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

A Sri Lanka without Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a steady supply of basic commodities and a stable economy may be major demands for many Sri Lankans in the south, yet for a real, lasting and comprehensive change across the board, difficult histories and harsh truths need to be engaged with, reflected upon and be made aware about.

These must provide the nucleus of Sri Lanka we wish to witness.

Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

People should engage and have long conversations about what has happened to the people during the war, It's something that must happen at all levels. Dialogue and communication are a must.

On the economic front, one of the primary concerns women have is the breakdown of Samurdhi, a much-needed social security net that communities in the east depend on. Simon, Rajaratam and Vasuki are nevertheless sceptical about how much these subsidies trickle down and reach the people that need them most and how effectively the subsidies are managed. During the COVID-19 lockdown, the allowance that was given to communities was actually from the reserve of the Samurdhi fund and now there are concerns about how much money remains in the fund, says Simon. With the Samurdhi allowances not coming through like they should and with the reserves being close to exhaustion, it's going to affect the poorest of the poor.

‘We are essentially being robbed.’

In the midst of this, the women are also concerned about how an IMF program may affect the social security schemes like Samurdhi that they (in spite of its issues) depend on. Villagers still try to manage by themselves, cultivating what they can.

Art by Kamala Vasuki. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

Paddy, corn, groundnuts, whatever will produce some sort of harvest without much fertilizer. This often ends up being inadequate for consumption, let alone sufficient to be sold. Whatever can be sold finds itself going outside the district. Those who had land during harvest time back then could produce enough paddy to feed their household with a surplus. Now they need to buy food that they once could grow because their own harvests are that bad and without any income, there's difficulty in even buying a farmer's basic staple.

Fishermen can’t go out to sea because of the fuel crisis. Those few that can bring in a catch sell it to the corporations. “Our communities can no longer buy fresh fish, we have to resort to buying tinned fish although these same fish are caught by our own fishermen,” Kamala says.

Art by Kamala Vasuki. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

There's no cultivation because of the fertilizer crisis. Cement prices soaring has meant there's little to no construction work, either. The men are jobless, and the longer they are home, the more their frustrations increase and family disputes emerge. It's to no one's surprise that domestic violence is on the rise, says Simon.

‘Whatever we hear on the news is just depressing because all we hear is bad news over and over again.’

It is the local produce that has kept this economy afloat, yet a large amount leaves the very communities that produce it. It is a big concern for women on the ground.

It has to benefit us first and others later. That is the economy we need. Yet no one listens to us, recognizes us or hears us out. It is breaking this hierarchy that is required.

Women continue to function as the buffer for all shocks and disruptions that these regions have been going through. Through the pandemic, the war, natural disasters, and even now, it is the resourcefulness of the women that has found a way through.

‘Let's unite to create a dignified society free from violence.’ Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

“Women's voices need to be heard. Change should happen through women's representation; representation goes even beyond politics, beyond just saying that there is equality because it is the amendments and constitution. We have to witness it in our life. Women have been asking for this simple recognition and equality for a long time.”

What's to be taken back from visiting the protest site at Galle Face? The question elicits some guarded answers. There’s certainly solidarity and hope in the messages that will be conveyed to some (understandably) sceptical communities back home.

A united struggle against power. Image via Groundviews, used with permission.

Yet the memory of fear and repression that Gotabaya Rajapaksa built his name on is still fresh in Simon's mind. “The Terminator” may have been rescaled and disarmed by the collective anger that continues to fuel the GotaGoHome movement in the south, but what is to happen outside the reaches of Colombo, in the north and east is still unknown. The Bar Association's lawyers don't line up and rush to court to fight injustice after injustice there where constant repression, surveillance, and intimidation are ingrained into a citizen's mind. It informs the cautious answer Simon leaves us with.

“We never wanted Gota, you are telling him to go home, so we came here to show our solidarity. But what happens after all this, if Gota does not go?”

“He will finish us off.”

Post a Comment