First to impose sanctions against Putin, Japan resists fully breaking ties

Originally published on Global Voices

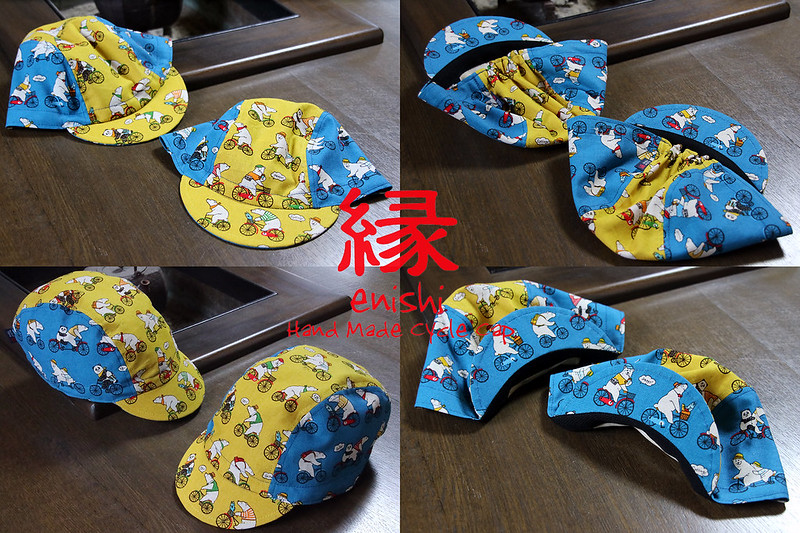

‘Pray for Ukraine’ cycle cap with Ukrainian colours, made by Enishi Handmade Cycle Caps in Kyoto. All sales proceeds are donated to Ukraine relief efforts, and the caps have all been purchased.. Note: The character “縁”, en, can mean “a bond or link that connects two people together.” Photo by jun.skywalker, from Flickr. Image license: Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Quick to impose economic and financial sanctions on Russia following that country's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Japan has also resisted fully breaking ties. The Russian invasion has also reinforced Japan as a country unwelcoming to refugees, and has shattered the nation's rejection of nuclear weapons.

In an historic March 23 address by video link to over 710 elected members of Japan's National Diet, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy applauded Japan as:

[…] the first [country] in Asia to put real pressure on Russia to restore peace. Who supported the sanctions against Russia.

The Ukrainian president was careful to tailor his speech specifically to Japan, said Tokyo-based journalist Phoebe Amoroso in a television interview with CBC/Radio Canada:

For example, [Zelenskyy] mentioned the nuclear power plants that were at risk of Russian attacks in Ukraine. This refers to of course the Fukushima incident in 2011 […] that led to a nuclear meltdown.

Zelenskyy also spoke to the need for reconstruction in Ukraine after the war is over, and helping find homes for those displaced by war, a reference, Amorosa said, to the 38,000 people in Japan still displaced 11 years after the massive earthquake and tsunami in 2011 destroyed communities along the country's northeast coast.

In his address, Zelenskyy also appealed to Japan to help stop Russia’s invasion:

So that Russia seeks peace. And stops the tsunami of its brutal invasion of our state, Ukraine. It is necessary to impose an embargo on trade with Russia. It is necessary to withdraw companies from the Russian market so that the money does not go to the Russian army.

Japan has displayed a mixed response to the crisis in the month since the start of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In the early days of the invasion, as the Japanese government acted to quickly impose sanctions on Russia, crowds gathered across Japan in support of Ukraine:

ステージから見た皆さんの意志と声。

スマホ片手に「意味がない」と冷笑する人はいるけれど、こうして足を運んで声を形にする人達がこれだけいるという事、そしてその人達1人1人が無力感に悩みながらも寄付や発信をしていく事の強さを確かに感じました。

本当に微力だけど、私は声を上げ続けていく。 pic.twitter.com/zUStmh104t

— 辻愛沙子|arca

(@ai_1124at_) March 5, 2022

The voice and the will of the people, seen from the stage.

There are people who sneer while looking at this, holding their smartphone with one hand, saying “It doesn't matter, anyway”, but I feel the strength of so many people who came here, one by one, even as they themselves may have been feeling a sense of helplessness to speak out, donate, and send aid.

It may feel like a small thing, but I'll keep raising my voice.

Note: Tsuji Asako is a media personality and television producer; this demonstration is in Tokyo.

Japan has been less enthusiastic about accepting refugees from Ukraine. In March, the government announced it would grant entry to 47 Ukrainians seeking shelter from the Russian invasion, an increase over the 30 refugees the country typically accepts each year.

However, Japan does not recognize Ukrainians as refugees, and grants them “temporary shelter” instead:

Japan is offering temporary shelter — a legal status that allows Ukrainians to stay and receive some support, but which falls short of recognizing them as refugees under international law.

— Hiroko Tabuchi (@HirokoTabuchi) March 6, 2022

Japan's economic sanctions can be similarly complicated. Some Japanese businesses have refrained from totally divesting in Russia since the start of the invasion, while the Japanese government has reversed some sanctions, and has refused, for now, to impose others.

In 2021, Japan exported over $7.3 billion in goods to Russia. Since the start of the invasion, besides banning the export of luxury cars to Russia, Japan has imposed a number of economic sanctions that target Russian President Vladimir Putin and business oligarchs. The Japanese government has also imposed restrictions on capital transactions with Russia, and has worked to exclude some Russian banks from international payment networks.

However, in March the Japanese government reversed a decision to ban imports of Russian sea urchin and crab, citing an “impact to society.” Russia is Japan's third-largest foreign source of seafood imports. Wholesalers, supermarkets, and the food service industry had already complained about product shortages following the start of the invasion in February.

While there is a growing awareness in Japan of the reputational damage of doing business in Russia, not all Japanese businesses find it easy to sever ties.

For example, Fast Retailing, Asia's largest retailer, best known for its Uniqlo fashion brand, reversed an earlier announcement that it would continue doing business in Russia after coming under fire from consumers.

Meanwhile, the Japanese government, Mitsui and Mitsubishi Group are so far reluctant to exit from the large Sakhalin-2 natural gas project, despite the abrupt exit of consortium member Shell following the invasion. Sakhalin-2 is the source of nearly 10 percent of Japan's liquefied natural gas imports.

It's estimated that exiting the project would cost the consortium US$15 billion, increase natural gas prices in Japan by up to 35 percent, and put the country's energy security at risk.

In any event, Japan's recent economic sanctions against Russia have chilled relations. The two countries technically remain at war because of a long-standing territorial dispute, and Russia, citing “anti-Russian” sentiment, announced in March that plans to conclude a peace treaty with Japan that would officially and finally end World War II were to be shelved indefinitely.

Russia's announcement, in turn, provoked Japanese prime minister Kishida Fumio to effectively end nearly two decades of expensive policy aimed at restoring Japan's “Northern Territories” — the four southernmost islands of the Kuril island chain, taken by the Soviet Union following the end of the Second World War.

On 7 Mar in Diet, Kishida described the N Territories as Japan’s “inherent territory”「固有の領土」. This has consistently been Japan’s position but, under Abe, the Japanese cabinet carefully avoided using the term publicly to avoid antagonising Russia. https://t.co/Bz5BjjqrWc

— James D.J. Brown (@JamesDJBrown) March 8, 2022

Russia then commenced military drills on the islands, which lie within sight of Japan's northernmost island of Hokkaido. The drills included Russia's S300 anti-aircraft system, which has a range of 400km, potentially threatening Japanese military and civilian aircraft in the area.

Russia's growing potential as a threat following the invasion of Ukraine has also sparked new debate in Japan about nation defense. Since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski in 1945, Japan has maintained its three principles of not possessing, not producing and not allowing nuclear weapons on its soil. In March, Japan's ruling coalition began a formal debate about a adopting nuclear weapons sharing agreement with the United States, similar to NATO.

In response, a representative of the Japanese Communist Party, one of Japan's larger opposition parties, said:

The three non-nuclear principles are not a mere policy measure but a national cause. A person who served as prime minister of the world's only atomic-bombed country in warfare should under no condition be talking about possessing nuclear arms.

Post a Comment