More indigenous people are talking about sexual and gender identity diversity

Originally published on Global Voices

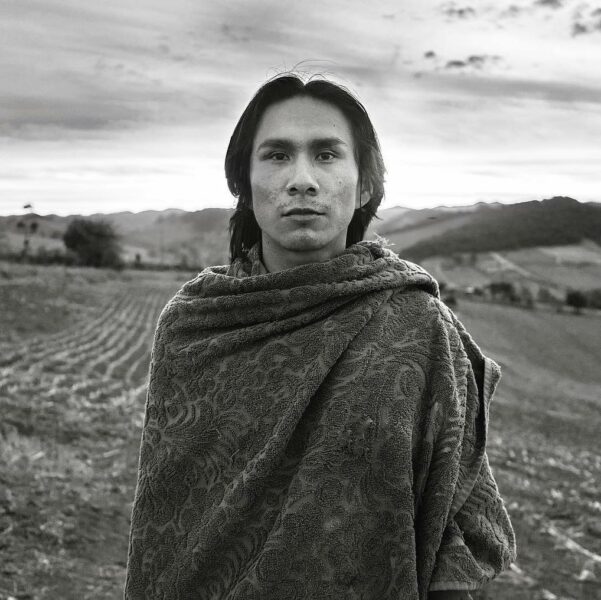

The subject is still taboo, but sexual diversity has been increasingly discussed, among Brazilian Indigenous. The image above shows the cacica Majur | Photo: Personal archive/Used with permission by Amazônia Real

This text, written by Keka Werneck, was originally published on the Amazônia Real website, in December 2021. It is republished here under a partnership agreement, with some changes.

Majur began to realize her identity as a girl at the age of 12. In Apido Paru village, on the Indigenous land of Tadarimana in Rondonópolis, in Mato Grosso state in Brazil's Amazon, where she was born and lives, this was never a problematic question. For a time, however, the woman of the Boe Bororo ethnicity did not fully understand what was happening within herself.

Today, at the age of 30, she identifies as a transsexual woman and is going through her gender transition, while also becoming a cacica (Indigenous chief), due to the retirement of her 79-year-old father for health reasons.

Since perceiving herself as trans, Majur has left the male name Gilmar Traytowu in the past, and has built her identity as a woman.

“I am undergoing [the transition] in stages. First, taking female hormones, under the supervision of an endocrinologist in Rondonópolis,” she told Amazônia Real in an interview.

Majur was hoping to access the transition treatment at no charge through the Unified Health System (SUS, the public health system in Brazil), but due to a delay, she decided to pay for the procedures.

In her village, in a state in central-western Brazil, Majur has always been respected. Now, as cacica, leading a community of about 800 people, she says that the respect has grown. She knows this is not the reality for most LGBTQIA+ Indigenous people, though.

“We, being Indigenous as well as LGBT, suffer double prejudice. While I have never suffered it from my parents, [I have] from some relatives, though, and in society generally as well,” she explained.

Even with the opportunity to leave the village to study, she decided to stay and work alongside her people. While she is single, she raises two nieces as if they were her own daughters — one of them, she says, has already given her “two little grandchildren.”

“I always say that our sexual [orientation] does not define our personality, we are what we are, not what homophobic society wants us to be,” she said, adding that she always thanks Aroe Eimejera, the “God, the Chief of Souls, the Chief of Spirits” of the Bororo people, for being well.

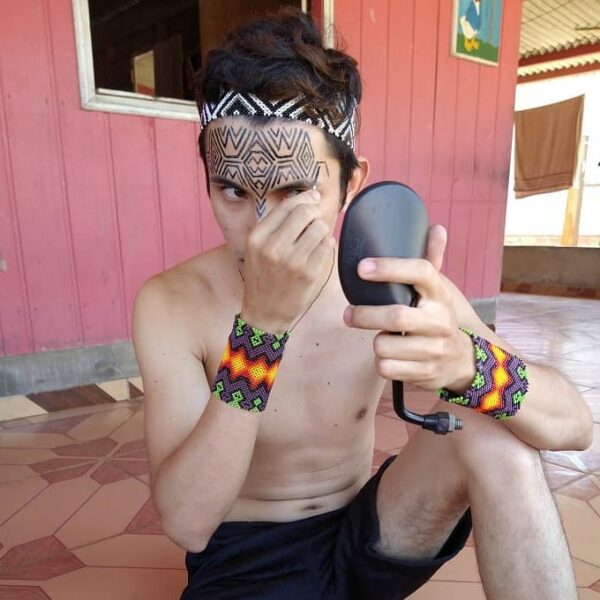

The Amazonian stylist Sioduhi | Photo: Jéssica Lagoas/Used with permission from Amazônia Real

Breaking the silence

A still taboo subject, sexual diversity in the villages has been gaining space with more Indigenous people deciding to break the silence.

At 25, Amazonian stylist Sioduhi, from the Pira-Tapuya people (also called Waíkahana), remembers how difficult it was to realize he was gay.

“This realization weighed heavily on me, specifically because I was born in an area with heavy colonization, which is the Upper Rio Negro in Amazonas. There is a high number of Catholics and Protestants there. It’s a place where colonization impacts in such a way that we all suffer from the process of integrationism,” he said.

Aware of his role in society, he has sought to guide this debate in a more open way.

“As an Indigenous, LGBTQIA+, stylist, who also has a certain influence, I have been talking more about these issues, which are still very delicate, due to the construction of binarism (man-woman) and Christian guilt, which is still very strong. We were told that we are going to hell,” he said.

When he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a stylist, he carried all this burden and history to São Paulo, which is reflected in his creative process. The alienation, and spiritual and moral violence also all went with him. It is not rare that an Indigenous LGBTQIA+ person ends up feeling isolated and oppressed within their own territory.

For the Waíkahana people, Sioduhi means “ancestral spirit of a baiá,” the singer of the sacred ceremonies. He was born and raised in the Mariwá community, in São Gabriel da Cachoeira, in Upper Rio Negro in Amazonas state. The region has the greatest diversity of Indigenous ethnicities, with 23 different peoples.

At the age of 12, he moved to the city to study. Three years ago, Sioduhi arrived in Pedras city, in São Paulo state. Resisting is what he has learned to do, being Indigenous, gay, and chasing his childhood dream of becoming a stylist. He created the label Sioduhi Studio, for Indigenous fashion.

Anthropologist Bárbara Arisi | Photo: Personal archive/Used with permission from Amazônia Real

Indigenous queer

Barbara Arisi, Ph.D. in anthropology at the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), is a researcher on sexual diversity among Indigenous people.

“My doctoral research was with the Matis, who live in the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory, near the border with Peru, where the Javari River separates the two countries,” she explained.

The Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory is in Amazonas State and is Brazil's second-largest Indigenous territory. More than 6,000 recently contacted and isolated Indigenous people live there.

The researcher's first book, “Gay Indians in Brazil: untold stories of the colonization of indigenous sexualities,” was published in 2017 by the Swiss publisher Springer, and talks about the untold history of Indigenous sexualities before the arrival of the Portuguese and Spanish.

“Chroniclers, priests, Jesuits, and Dominican friars recorded the presence of other non-monogamous, non-heterosexual sexual practices that the Indigenous peoples, as well as many other Indigenous people around the world, had accepted in the community, before European colonization,” explained the anthropologist.

“Heterosexism, the violence against practices that people would later call homosexual, is part of a process of Catholic cultural imposition over Indigenous practices relating to ways of establishing families, sexuality, affection.”

Her second book, “Queer Natives in Latin America: forbidden chapters of colonial history,” was published this year. It provides an overview of the scant literature on the subject as well as accounts of contemporary, queer, and transgender Indigenous figures.

“The book is about everything we found concerning material in archaeology, in the chroniclers’ records up to the more contemporary period, about how some Indigenous people today say they are ‘pueblos maricas,’ for example, a term used in South America,” she emphasized.

The book also provides information about Indigenous American and Canadian academics who call for the number two to be included in the diversity acronym: LGBTQIA2+. This is because they are Indigenous and not comfortable with binarism. They call themselves two-spirit, a native term. A similar term in Brazil would be “Indigenous queer”.

Tarisson Nawa | Photo: Personal archive/Used with permission from Amazônia Rea

Gender Fluidity

For the Nawa people in the northern state of Acre, according to journalist José Tarisson Costa da Silva, an Indigenous gay man, there are accounts that their ancestors expressed their sexuality in such a comfortable way that it was not necessary to declare one's sexual orientation.

“Sexuality didn't have this hierarchy or relationship of violence with people, with different practices. Nowadays, asserting oneself as an Indigenous LGBTQIA+ person is fundamental to the struggle, and for recognition. It is the difference within the difference,” he explained.

Tarisson Nawa, who currently lives in Manaus, capital of Amazonas state, highlighted that the issue of gender within Indigenous peoples is now being raised by Indigenous women's movements

“Because gender struggles bring about other ways of being and living within the territory,” Tarisson observed. “Together with the women's struggle, [and] the struggle for territory, linked to gender issues there are also issues of sexuality,” he said.

He notes that in most territories colonization directly affected the sexuality of Indigenous peoples, impacting their affections, sensibilities, and ways of making relationships. Just as it altered, and continues to affect, their societal organization.

“I have my reservations about saying that everything is a product of the violence of colonization. I'm not denying it, it is a fact that colonization had an impact, but we have to take into account that in Brazil there are 305 Indigenous peoples. The diversity is immense, it is difficult to measure to what extent the fluidity of gender and sexuality existed in all these territories before colonization,” he said.

For anthropologist Barbara Arisi, discrimination and prejudice against sexual diversity among Indigenous people depends on the context. While many communities, such as Majur's, are accepting, others are not.

“I always think that Indigenous communities are more accepting of people, but that doesn't mean all of them, it varies greatly, there are many peoples, you can't speak generically.”

Post a Comment