‘We cannot talk about climate justice if we don't talk about climate injustice’

Originally published on Global Voices

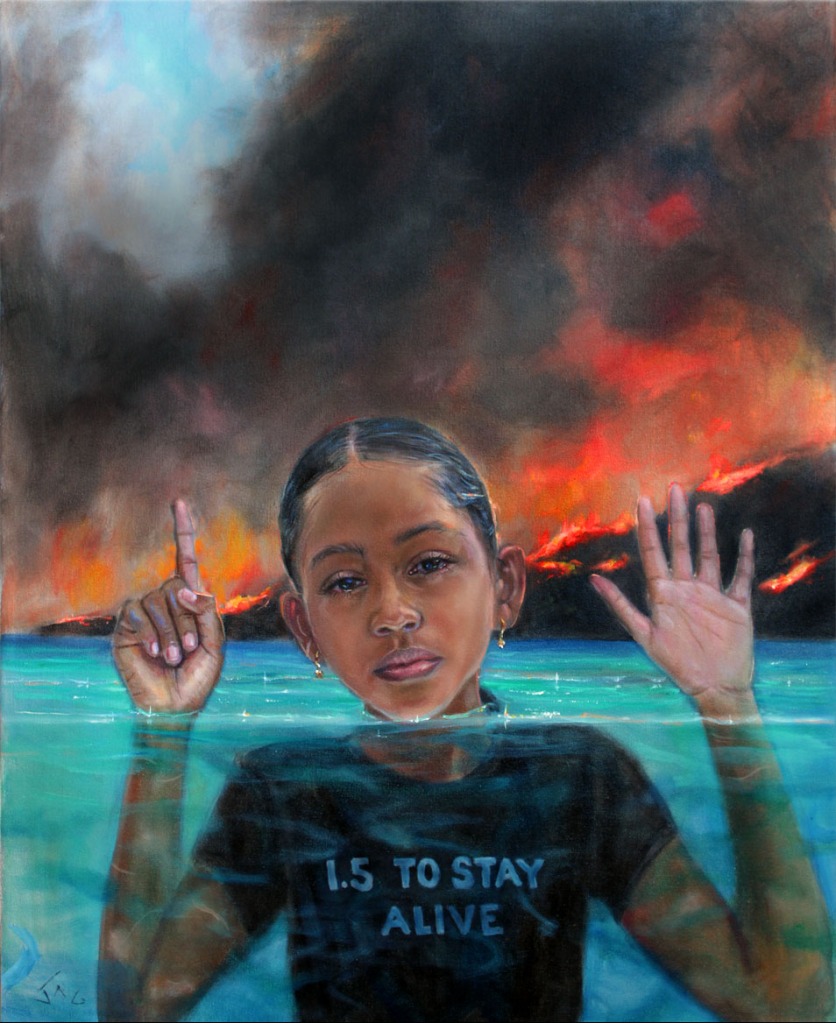

St. Lucian-American artist Jonathan Gladding‘s most recent “1.5 to Stay Alive” painting, used with permission.

After two intense weeks of panel discussions, side events, networking, and speeches by political leaders, Glasgow's UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) is behind us—and already fading from the media spotlight. Looking back, what can Caribbean nations take away from it, and where do they go from here?

Yves Renard, board member and regional coordinator of the non-governmental organisation Panos Caribbean, shared his post-conference reflections with me from the village of Laborie, Saint Lucia, where he lives and works.

For over four decades, Renard has been involved in sustainable development policy and participatory natural resource management in the region. He's particularly interested in linking natural resource governance with poverty reduction and social development, and in designing institutions that foster participation and empowerment.

Yves Renard, board member and regional coordinator of the non-governmental organisation Panos Caribbean, which has been an active advocate for the region when it comes to the climate crisis. Photo courtesy Renard, used with permission.

Yves Renard (YR): The slogan ‘1.5 to Stay Alive’ was actually first coined by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) when [Grenadian diplomat] Dessima Williams was its chairperson. In 2015, following a discussion between Dr James Fletcher of Saint Lucia and Panos Caribbean, it was decided to design and launch a campaign with the primary objective of supporting Caribbean negotiators at COP21 in Paris. Media, artists, young people were mobilised to amplify their voices and to make Caribbean negotiators feel that people at home were aware of the issues and supported their efforts. That campaign used the slogan, with the iconic images of [artist] Jonathan Gladding, [to] forcefully convey the message.

EL: What if 1.5 is not achievable?

YR: This is very hard to tell and we have to believe the science. As NASA succinctly points out, ‘The potential future effects of global climate change include more frequent wildfires, longer periods of drought in some regions and an increase in the number, duration and intensity of tropical storms.’ We have to accept that many scientists now see a 1.8° Celsius increase as the ‘optimistic’ scenario and that there is no place for complacency. This 1.8°C scenario assumes full implementation of all the targets announced and commitments made. Let us keep in mind that we are now at 1.2°C above the pre-industrial levels of 1850-1900.

EL: The Caribbean is very much focused on climate finance. Coming out of COP26, do you think a more equitable source of finance that will make a real difference at the grassroots, community level is now possible?

YR: It seems that COP26 made very little progress with respect to financing for Loss and Damage. There was a proposal to create a Glasgow Loss and Damage Finance Facility which was supported by all Caribbean countries, but which was not adopted in the final declaration. Instead, the focus was on the operationalisation of the Santiago Network, but this is not a financing instrument; it is only a mechanism to facilitate the exchange of expertise and information.

There was, however, some encouraging news, with a significant increase in funding for adaptation, including over 350 million United States dollars in new pledges to the Adaptation Fund, which has a good reputation of reaching the ground and working at the grassroots level. In addition, there were several important conversations at COP26, spearheaded in particular by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and the Caribbean Natural Resources Institute (CANARI), which stressed the importance of climate finance reaching the most vulnerable and demonstrated how this could be done.

EL: Are we therefore any closer to obtaining support for the “Loss and Damage” component of financing, which would have to be in addition to current pledges?

YR: From what I know, it doesn't seem so, except that the idea of the Loss and Damage Finance Facility is still on the table, and some private philanthropic organisations, such as the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Open Society Foundations, have offered to provide support to get it started.

The most well known image of the “1.5 to Stay Alive” campaign, by St. Lucian-American artist Jonathan Gladding, used with permission.

YR: For me, we cannot talk about climate justice if we don't talk about climate injustice and if we are not prepared to fight that injustice. We talk about climate justice because the climate crisis exacerbates social injustice: poverty increases vulnerability to disasters. Women, especially those who are heads of households, have a special burden to carry when they are impacted by storms, floods or landslides. Poor households typically cannot afford insurance.

There is another dimension of climate justice which is about fairness in international negotiations and relations. Climate justice is also about the countries and economic sectors that are most directly responsible for the current crisis accepting that responsibility, and acting accordingly.

The abuse and misuse of the concept of climate justice, in my view, comes because it just sounds absolutely right. So everyone wants to be associated with such a righteous concept, even when doing things that have little, if anything, to do with combatting injustice. It can be achieved by putting the response to the climate crisis at the core of some of our main policies, such as social policy, land policy, agricultural policy.

EL: In its pre-COP statement, Panos Caribbean stressed that we must “look at ourselves” and our own practices at home. Do you think that Caribbean leaders will now make some positive changes, or will it be business as usual? What are some impactful measures they can take—especially now, as time is short?

YR: Imagine if all Caribbean countries in 2022 agreed to a post-COP26 statement outlining what they will do, concretely, to reduce their vulnerability. This action plan would have to be very specific and deal, for example, with the issue of dredging for cruise ship ports with agreed coastal construction setback, or the complete and effective ban on illegal and destructive mining. I fear that this will not happen, and that the urgency of economic recovery in the wake of the pandemic is already fuelling investments that are incompatible with the objectives of reducing our vulnerability.

EL: Finally, what do you think the Caribbean has gained from COP26? Are we likely to be moving closer to true climate justice, which goes hand in hand with greater social justice?

YR: The move towards climate justice will depend largely on what we do at home, ourselves. We should, however, accept that COP26 did a few things that are important to us. The goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement was ‘to limit global warming to well below two, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels’. Thanks to the IPCC report, the passionate speeches of young climate activists, the eloquent speeches of world leaders such as [Prime Minister] Mia Mottley of Barbados, and the media coverage of COP26, it has been made clear that it is not a question of ‘preferably'—1.5 has to be the target. But that target will not be reached without the phasing down of coal and the just transition that so many spoke about in Glasgow.

Post a Comment