Pressure and censorship lead to reshuffle in popular news outlet.

Originally published on Global Voices

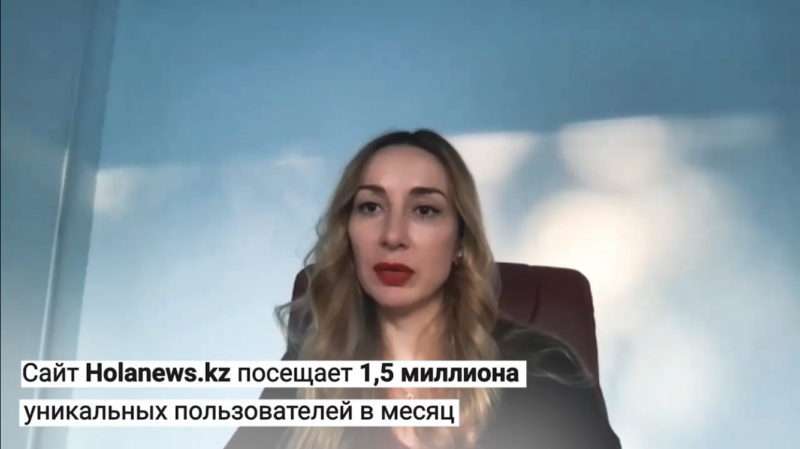

Former Hola News editor Zarina Akhmatova during an interview about the blocking of their website. The caption reads “Every month, 1.5 million unique users visit the site Holanews.kz.” Screengrab from the YouTube channel Dergachyov Insight.

In the same hours of the Facebook shutdown on October 4, one of Kazakhstan's most popular news websites, Hola News, went offline, and not from a technical mishap. The facts concerning the causes and the 10-day duration of the shutdown were never clarified by the authorities.

The site, followed by hundreds of thousands on social media, had published on October 4 an article about the OCCRP investigation into offshore companies possibly linked to the country's former president.

Fearing that the blocking could be linked with this article, the founders, Alisher Kaidarov and Adilet Tursynbek, and editor Zarina Akhmatova decided to take it down from their servers on October 5. The following day, they noted that the blocking seemed to be due to a Deep packet inspection (DPI), a technology often used by governments to censor online content.

Instead of the original piece, they published an empty article that resembled a death notice. “Here was the headline,” “here was the image,” and “here was the body of the article,” the webpage that was self-censored now recites. At the bottom of the page, the only addition was a YouTube video of the ‘There's nothing better in the world!’ introduction song to the Soviet cartoon version of the Town Musicians of Bremen.

A screenshot of the censored article now at Hola News.

This looked like an epitaph to the existence of Hola News, born in 2018 in the midst of a hostile environment for news outlets in Kazakhstan. Immediately after the website was back online, in fact, Kaidarov, Tursynbek, and Akhmatova resigned with a public note denouncing the pressure on them.

After being blocked for 10 days, we had to give up our basic principles [of honesty and objectivity]. We have removed the article from the site. […] That is why we believe that, in order to remain yourself, leaving is better than staying.

The Adil Soz, a local freedom of expression watchdog, officially filed a statement against the blocking of Hola News with the Ministry of Information's web portal.

The blocking was a harsh measure against Hola News, especially given that other outlets had covered the same news and the Semey City website had copied and shared Hola News's original text.

Observers debated whether the event was a “one of a kind” or a “sign of warning for others.” Nurzhan, a political analyst who asked to withhold his last name, told Global Voices that “the government likely targeted Hola News because of its large following.” Besides the 1.5 million unique monthly visitors to its website, Hola News has a large social media audience.

In the latest Freedom on the Net report by Freedom House, Kazakhstan was classified as not free due to its obstacles to access and its limits on content. The report highlights how news sites often have to resort to self-censorship to survive.

Self-censorship in the media is pervasive, even among independent online news outlets, because existing legislation often contains ambiguity.

The Pandora Papers leak — with its almost 3 terabytes of data spread across 12 million documents from service providers in offshore jurisdictions — is poised to further expose opaque deals concerning politically exposed people in Kazakhstan. From this perspective, the blocking of Hola News could be a precedent, as others might choose to self-censor in prospective investigations.

Besides new legislation and the absence of security tools available elsewhere, Kazakhstan has proved to be a hostile environment for journalists. Some were targeted with spyware, as unveiled in the Pegasus Project investigation in July.

Hola News could now face the fate of several other media platforms, which had to choose self-censorship over independence to survive.

Post a Comment