More evidence of tigers moving out of their traditional habitat

Originally published on Global Voices

Tigers (left-female/right-male) photographed during the Chure study in the forests of Kapilvastu, Rupandehi, and Palpa. Image via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

This article was originally written by Tufan Neupane in Nepalese in Himal Khabar and a translation by Sonia Awale was published in the Nepali Times. An edited version is republished by Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement.

A new paper has reported fresh sightings of wild tigers in higher elevations in Nepal, showing that conservation efforts need to be stepped up outside their traditional habitat inside national parks.

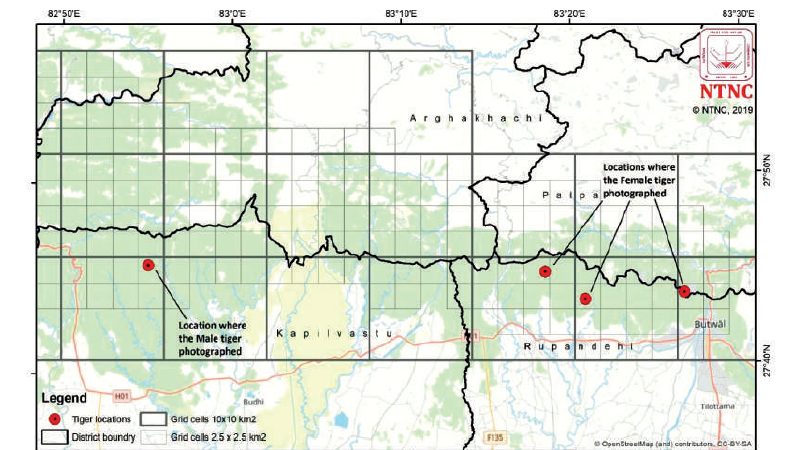

There have been multiple sightings of at least two tigers in the mountains of Rupandehi, Kapilvastu and Palpa, three districts in central Nepal that have never before seen the presence of the endangered big cats.

“We have camera-trapped tigers in forests north and west of Butwal where they have never been seen before. They have been seen in the Chure Hills, outside of protected areas in the Terai region,” says Baburam Lamichhane of the Sauraha Biodiversity Conservation Centre.

The recently published ‘Report on Faunal Diversity in Chure Region of Nepal’ identified a female tiger in multiple locations on the border of Rupandehi and Palpa. A male was spotted in northern Kapilvastu, about 40km west of the female.

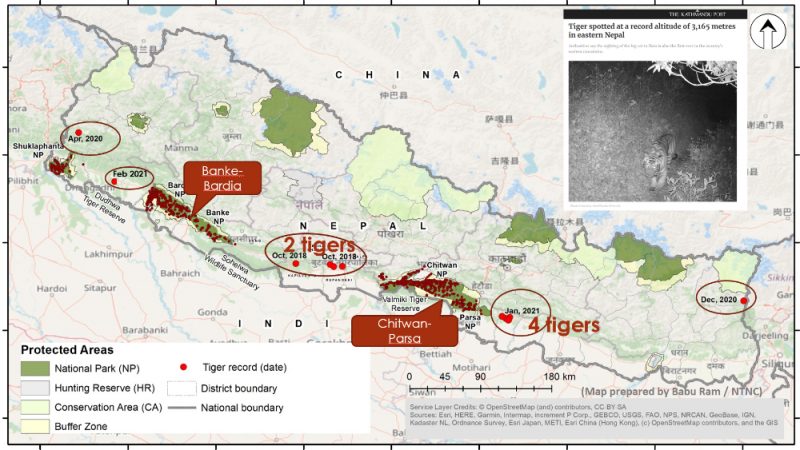

Nepal’s five Terai national parks (Parsa and Chitwan in the east and Banke, Bardia and Shuklaphanta in the west) are considered the traditional habitats of the big cats in Nepal. Kapilvastu, Rupandehi and Palpa districts in central Nepal are equidistant from Chitwan-Parsa in the east and Banke-Bardia in the west.

Individual tigers can be identified by signature stripes on their bodies, so researchers compared camera trap images of the newly discovered tigers with those previously spotted in Chitwan, Parsa, Banke, Bardia and Shuklaphanta during the censuses in 2009, 2014 and 2018, but there were no matches in the tiger data base.

Nine months ago, a newly-identified female tiger was reported to have attacked a villager 25km away from the area where it was spotted. Since these two locations are connected via a forest corridor, conservationists speculate that it may be the same tiger.

Seven conservationists including Lamichhane and Naresh Subedi have tried to find out whether the recently detected male and female tigers have crossed paths and mated. They do not know for sure yet.

Another study carried out by NTNC and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) spotted four tigers this year in a forest in Rautahat bordering Parsa National Park.

Apart from these, the big cats have been seen roaming the Brahmadev-Laljhadi corridor of Kanchanpur district in the far-western plains. Another strip of forest in Kailali connecting Shuklaphanta and Bardia National Parks has also recorded tigers.

The Kamdi Corridor, which connects Banke National Park with India’s Suhelva Wildlife Sanctuary and facilitates the movement of wildlife between the two countries, is home to abundant tigers. They have also started appearing in the hill forests north of Chitwan National Park.

In the last census in 2018, Nepal counted 235 tigers in five national parks, becoming the first country to double the population of its big cats, from 121 in 2009. Chitwan National Park had the highest number of tigers at 93, followed by Bardia that registered 87 individuals and Banke 21. There were 18 more in Parsa and 16 in Shuklaphanta.

However, the census did not cover areas outside national parks, and the real total number of tigers could therefore be more. Nepal is an international model for tiger conservation but its successes in increasing the big cat population mean protected areas are getting crowded, in turn leading to a sharp decline in prey density. Tigers are now venturing outside of forests in search of food.

Researchers have also cited other reasons for tigers venturing up the Himalaya: climate change and the success of Nepal’s community forestry efforts in the mountains.

“Tigers do not leave their territory unless it must, so they are out looking for new habitats,” explains Haribhadra Acharya of the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC). “While their sightings are proof of our conservation success, it also adds to the challenge. Contact with people outside parks has increased, which is worrying.”

The good news is that recent studies have shown the possibility of linking the protected areas in eastern and western Terai. An article published in the Journal of Animal Diversity recommends expanding conservation efforts outside national parts, and spreading it throughout the country.

In December 2020, Nepal recorded its highest ever tiger sighting at 3,165m in Ilam district. In April 2020, a Royal Bengal tiger was caught on a camera trap roaming the forested mountains of Dadeldhura at 2,500m. Given that this forest is connected to Shuklaphanta National Park in the Terai, the tiger may have climbed to the higher elevation from the plains.

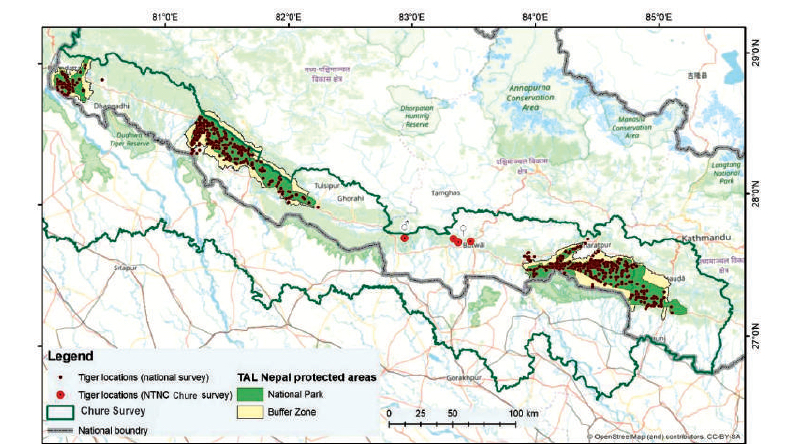

Records of tigers in Chure during this study in relation to tiger distribution in Nepal based on National Study in 2018. Image via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

But the tiger found in Ilam is unlikely to have come from the Parsa-Rautahat forest in the eastern Terai because it is too far, and the stretch in between has dense human habitation.

However, the forest in Ilam is connected with India’s Singalila National Park, the Neora Valley National Park in Sikkim and protected areas of Bhutan — all of which have forest corridors and have also recently sighted tigers. This has led experts to speculate that the tiger in Ilam may have ventured in from Sikkim, or even Bhutan.

Close-up of the locations where tigers were camera-trapped in Kapilvastu and Rupandehi. Image via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

Baburam Lamichhane of NTNC says, however, that the increased sightings should not be understood as habitat expansion: “We are seeing tigers in new places but it doesn’t mean they are permanently moving there. It does mean we have to protect their habitats.”

The sightings of tigers outside parks and in the mountains has raised the need for cross-border cooperation in tiger and nature conservation.

Says Acharya of DNPWC: “These sightings do indicate tigers have chosen to be in the highlands because they like it there. Our priority now is to protect the habitats also outside national parks, ensure adequate water, and prey.”

Post a Comment