In five months, Haiti's reported abductions have more than doubled

Screen capture from the video tribute to Evelyne Sincère, published on Tele Ginen’s YouTube channel on 6 November

On October 29, 22-year-old Evelyne Sincère was kidnapped after taking her end-of-year exams and her body was found in the Delmas 24 neighbourhood of Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince on November 1. News of her death sent shockwaves across the country, raising fears about a rise in ransom kidnappings and highlighting fears that the government wasn't doing enough to stop them.

According to the United Nations, between January 1 and May 31, Haiti saw a 200 percent rise in the number of reported abductions. Among the cases reported to Haitian police were 57 males, including 11 minors, and 35 female kidnapping victims, including 8 minors.

However, according to Laënnec Hurbon, research director at the CNRS multidisciplinary research association and professor at the State University of Haiti, the official reported figures do not capture the full extent of the issue. In his opinion, Hurbon states that no fewer than 1,270 kidnapping cases were registered in Haiti between January and August, which adds up to approximately 160 abductions a month.

Haitians demand justice

Ten feminist organisations, including Kay fanm, SOFA, and Neges Mawon, signed a joint letter on November 7 declaring that Sincère's murder was not an isolated incident but rather the result of a “failure to respect human rights” resulting from “the impunity and irresponsibility of the state authorities”.

Students from Sincère's school, the Lycée Jacques Roumain, took to the streets to demand justice, and “denounced the rise in acts of kidnapping in the country and the weakness of the authorities aimed at guaranteeing the safety of the population”.

Commemoration ceremonies for Sincère were organised in Port-au-Prince, and social media has been full of messages of solidarity.

Former President Jocelerme Privert condemned Sincère's murder, condemning an “outflow of insecurity sowing grief in families and killing hope in the young.”

Journalist Sindy Ducrepin comments on Twitter:

Une victime de trop. Des larmes de trop. Des coupables à jamais libres dans la nature. Des enquêtes de la Police avortées. Davantage de mauvais souvenirs qui ne partiront jamais. Une soif de justice pour toujours inassouvie.

#EvelyneSincere

— Sindy Ducrépin (@SindyDucrepin) November 3, 2020

Another victim too many. More tears too many. Perpetrators still at large, scot free. Police enquiries called off. More painful memories which will never go away. A thirst for justice forever unassuaged.

One of the public tributes:

In honor of her life, Haitian influencers, friends and supporters have gather at the location where Evelyne Sincere’s body was found in Delmas, to clean up, add flowers, paint, and pay tribute to her.

pic.twitter.com/2QnaMfyJ6a

— Lunionsuite

(@LunionSuite) November 6, 2020

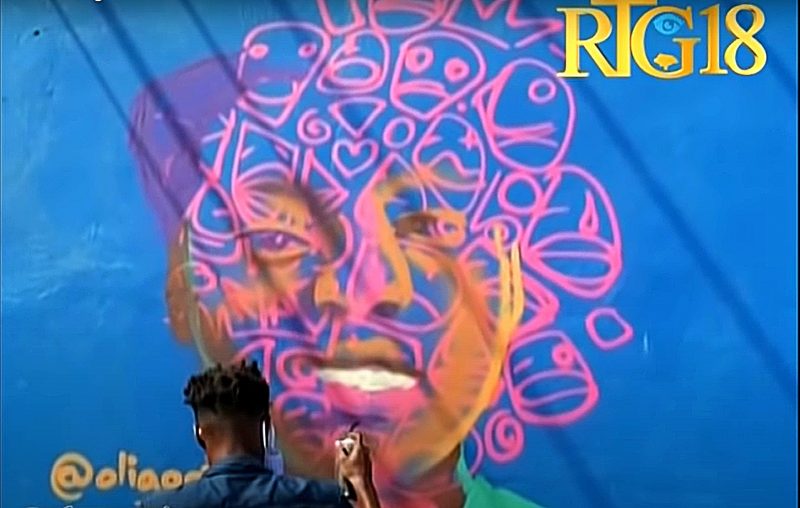

Another in the form of wall artwork in memory of Evelyne Sincère:

Évelyne Sincere, fly high our sister

#Haiti pic.twitter.com/f8HtwNktRW

— @HaitiMania #PetroCaribeChallenge (@HaitiMania) November 6, 2020

Many have expressed their bewilderment on Twitter:

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère

Évelyne Sincère— Thamzzz_The_CEO

(@thamzzz_luxury) November 7, 2020

“The proliferation of armed men, the uncontrolled circulation of illegal firearms, and growing insecurity touch every aspect of life in Haiti,” explains the online news site Ayibopost, which reports that official figures estimate 80 local armed groups were active in Haiti in 2019. Criminal activities in the country are also thought to be facilitated by the current government’s links with these armed groups. The rise in kidnappings is happening within a wider context of crime, impunity, political instability and economic crisis.

A new modus operandi for kidnapping seems to have developed over the last few years in Haiti with gangs now kidnapping entire public buses. Abduction victims in Haiti are targeted according to the sum the gangs can demand in ransom. Generally calculated in US dollars, these ransoms can go as high as $500,000, or even $1 million.

But kidnap victims are not all “high rollers”. “Little people, sidewalk traders, bank staff, workers, educators, or the sons and daughters of poor families” are also at risk of being abducted, claims Laënnec Hurbon.

Indeed, the kidnapper may even be part of the victim’s inner circle and not be part of a gang, as in Evelyne Sincère’s case. The abductors, who included the victim’s alleged boyfriend, had asked for a ransom of 100,000 US dollars as they believed her family was wealthy, but, by the end of negotiations, ended up accepting the sum of 15,000 dollars. It is not clear whether they received the money and Sincère was executed a day before she was supposed to be freed. Three suspects have been detained, one of which was handed over to the police by a famous gang leader, Jimmy Cérisier.

The passivity of the country’s authorities in the face of kidnapping in Haiti has been denounced, notably by the organisation New England Human Rights Organization:

Throughout the Port-au-Prince metropolitan zone and in provincial cities, citizens from all social backgrounds are prey to lawless armed bandits, going unmolested and, above all, unpunished.

Public opinion has criticized the Haitian National Police (PNH)’s handling of Sincère's case. One Facebook user, for example, accuses the PNH of lying and staging Sincère’s presumed killers’ interview. On Twitter, economist and political activist Jeffsky Poincy denounced the PNH’s failure to respect civil rights and highlights the fact that a public interview was held without the presence of the suspects’ lawyers. He believes that the lack of due process for the suspects is a symptom of unstable institutions and rule of law.

Post a Comment