Online harassment requires attention, reform and strong legislation

Alaa Salah has become a symbol for the role of women in the uprising against Sudan’s autocratic leader Omar al-Bashir, who was ousted by the military. Footage of her singing traditional songs at protests in Khartoum went viral on social media, where women and minorities in Sudan often face intense online harassment. Screenshot via VOA/YouTube, April 16, 2019.

Over the last few years, the internet in Sudan has played an increasingly important role in politics and society. During the Sudanese revolution in 2019, protesters and activists turned to social media to communicate, organize and document violations.

Their efforts eventually toppled Omar al-Bashir, who ruled the country with an iron fist for 30 years.

Despite these achievements, online harassment continues to be a major problem in Sudan, where internet penetration is estimated at 31 percent. The harassment — including doxing, cyberbullying, stalking, and hate speech — particularly impacts women and minorities.

Various campaigns have tried to address these violations, but harassment online requires more attention and reform — including the enactment of strong legislation.

In July, a Sudanese Facebook page reshared photos of Weam Shagi, a known Sudanese women's rights activist, that showed her experiencing torture during the dispersal of a sit-in by security forces in the capital, Khartoum. Shagi had earlier shared these photos on her own Facebook page. A number of commenters used body-shaming language to attack her.

This is just one of many examples of online harassment in Sudan.

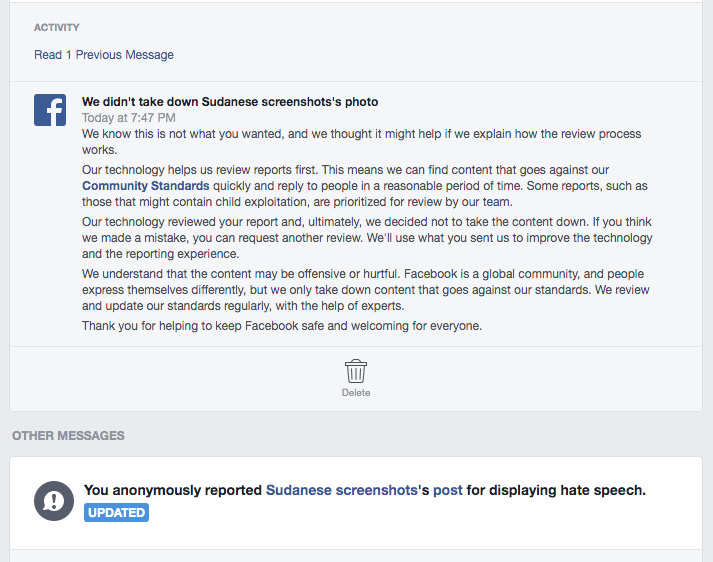

Mocking people based on their geographical region is also common. In August, a known Facebook page with 170,145 followers called “Sudanese Screenshot” shared a post that mocked girls from Omdurman, commenting that the girls should be used as a tool to stop the deadly Nile floods currently sweeping through Khartoum and Bahri. The comments insinuate that these girls are less valued and less beautiful, based on their region of origin. When the post was reported, Facebook responded that the post did not violate its community standards.

Facebook found that a post whose author mocked girls from Omdurman, saying that they should be used to stop the Nile floods, did not violate its community standards. Screenshot taken by the author, September 23.

Online harassment is not exclusively practiced by individuals. The military has also previously engaged in malicious online behavior. In June, according to a report by Human Rights Watch, “army personnel threatened a young woman protester who appeared on a widely circulated social media clip chanting against the military. She and her family received several calls from men who identified themselves as military officers threatening a lawsuit against her for ‘use of curses against the army.’”

In some cases, online harassment has been used as a tool to intimidate political activists by the former regime.

According to the 2018 Freedom on the Net Sudan Country Report, “over 15 female activists were doxxed on the fake Facebook page “Sudanese Women against the Hijab,” where their private pictures were posted without their consent alongside fabricated quotes about being against the veil and religion.” The page was later removed by Facebook after many reported it as a violation of the platform’s community standards.

Sudanese women respond

In the past few years, Sudanese women employed a number of tactics to protect themselves against continuous online harassment. For example, a group of women created a Facebook group called “Inboxat,” a tweak of the English word “inbox,” to expose their harassers by sharing the messages they sent.

Despite the group’s relative success, some criticized them for sharing their harassers’ screenshots of abusive content because it possibly violated their privacy.

Hashtags have also been used to call out online harassment. For example, the “expose a harasser’’ hashtag is still actively used by Sudanese women to share their personal stories. The hashtag morphed into a tool for online discussions about the nature of harassment and the pros and cons of exposing it, though some argue this might also invade privacy and could lead to defamation.

Online harassment can lead to major psychological consequences such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress, yet it remains an under-investigated topic. According to published research by Amnesty International in 2018, women polled in eight countries reported feeling physically unsafe and experiencing anxiety and panic attacks because of online harassment.

Role of online newspapers and magazines

Online newspapers also engage in online harassment. In December 2016, Sudafax, an online Sudanese newspaper, published a series of articles about Ethiopian immigrants living in a Khartoum neighborhood, in which they cited complaints by residents that were riddled with abusive, racist language.

The articles featured hateful headlines such as “The colony of Ethiopians,” and “Sudanese Addis,” stoking anti-immigrant sentiments toward Ethiopians in Sudan.

Many readers in the comments section criticized the newspaper for publishing such hateful speech online, but until now, the newspaper has not taken any action to address these concerns and Sudafax does not have an official content policy.

An analysis of 25 Sudanese news websites, online forums, and magazines shows that only a few publish content policies regarding harassment and hate speech. Sudaneseonline, a well-known online platform, shares its content policy that promises to remove spam or abusive language but fails to address harassment. Many other platforms do not share policies related to content moderation at all, even though some share rules related to users’ privacy protection.

Vague laws

Sudan currently does very little to protect women and other at-risk groups and communities from harassment, threatening to diminish their ability to exercise their fundamental rights online, along with their well-being and mental health.

In December 2016, the Sudanese government published a national strategic framework to protect children and youth online. The strategy included a 2018-2020 work plan and explicitly addressed harassment targeting children, legal shortcomings — and the need for awareness-raising.

The Sudanese legal system itself does not directly use the term “harassment,” but other vague terms that fall under the category appear in various legal documents.

For example, the 2007 Cybercrime Act prohibits behavior such as “intimidation,” “incitement” and “blackmailing.” The Act also prohibits sending material that violates the “sanctity of private life.”

By contrast, the 2018 IT Crimes Law prohibits the use of “any communications or information means, to incite hatred against foreigners, causing discrimination and hostility.” However, the final draft of this law has not been shared with the public and it was passed by the deposed regime.

In June 2018, the Sudanese parliament passed an amendment to the 2009 Press and Journalism Law that added online journalism to its content. Article 26 of the law prohibits journalists from disseminating racist content online.

To address — and stop — online harassment, lawmakers must reform current legislation to include clear definitions of all types of harassment such as doxing, cyberstalking, discriminatory speech and threats of violence.

Legal reforms should also be enacted in accordance with international human rights standards and should not be used by the government as an excuse to undermine the fundamental right to freedom of expression.

This process should also involve vulnerable groups such as women and minorities who are often left out of this discourse, yet are the most affected. Previous cases should serve as examples to understand the complexity and evolving nature of this problem.

Post a Comment