Neither internet blocks nor police violence have hindered Belarus’ networked protest

A mass demonstration against President Alyaksandr Lukashenka in central Minsk, Belarus, August 16. Photo: Homoatrox / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0. Some rights reserved.

This article originally appeared at oDR, openDemocracy's section on Russia and the post-Soviet space. It is republished here with permission, and has been edited for style and brevity.

Over the past decade, experience has shown how large protests at a single public square – like those in Cairo’s Tahrir square or Kyiv’s Maidan – can lead to real political change. At the same time, when state authorities are responsible for allocating spaces to protest – as was the case with Bolotnaya Square and Sakharov Square in Moscow in 2011 – even mass protests can end in nothing.

During the first two nights after the August 9 election results, the Belarusian authorities brutally suppressed protesters’ attempts to gather in the central squares of Minsk. This led to the protests dissipating and acquiring a hyperlocal character, whereby protests were not concentrated at a single point, but flared up simultaneously in different places, from street to street, from neighbourhood to neighbourhood.

This “scattered” protest had important advantages. Firstly, citizens themselves determined the protest’s course and the conditions they set, rather than the state bodies which authorised the demonstrations. Secondly, the “scattered” protest became a transitional stage ahead of protests on the square: a week later, on August 16, the protesters managed to reach Government House in the capital of Minsk peacefully and without resistance, and to gather at a nearby important war monument. This peaceful protest was now much more significant in terms of numbers than the pro-government rally in support of Alyaksandr Lukashenka.

Taking to the streets en masse, individual citizens have been integral to the success of Belarus’ protest, but so have enterprise and factory collectives – that is, group actors. How did the protest reach such a wide audience so quickly? It can hardly be said that internet channels have played a central mobilising role here, especially given the partially successful attempts of the Belarusian authorities to block the internet.

Despite the incredible growth in popularity of a number of Telegram channels (for example, the number of subscribers to the popular Nexta channel increased by 1.5 million in a matter of days), these information streams remained inaccessible to many inside Belarus, with a significant part of this growth in the channels’ popularity associated with the global audience. At the same time, it is important to note the high level of IT literacy in Belarus, where industries related to information technology have been actively developing in recent years. This level of literacy allowed significant numbers of people both to partially bypass the blocking of the internet and produce protest-related content.

Instead, the key question to understanding the role of the internet in the Belarusian protests is: how has the cost of using violence exceeded its effectiveness for the state? In the Belarusian scenario, the internet did not become a key mechanism for mobilising and coordinating protests, but it did create conditions in which the rapid and mass involvement of citizens became possible. This can be attributed to two important characteristics of the protests: unprecedented state violence and the dispersed nature of the protests both in the capital and throughout the country.

When hyperlocal protests take place in the context of the modern information environment, even the most brutal violence does not achieve its goal of suppressing protests, but only contributes to their growth.

The fragility of the digital horizontal

For more than a decade, researchers have debated the internet’s importance for the success of political protests. Internet technologies have played a large role both in protests that brought about serious political change (for example, the Arab Spring or Euromaidan) and those that did not lead to a change in power: during the elections in Iran in 2009, in Russia in 2011-2012, or during the Gezi Park protests in Turkey in 2013. On the one hand, researchers have pointed to a wide range of political and technological innovations that increase transparency of covering protests, as well as facilitating the mobilisation and coordination of actions.

In this vein, Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg have discussed the emergence of a new type of collective action, dubbed “connective action”, that allows joint actions to be organised without the need for any formal organisation or party. Institutions are replaced by digital platforms in this model, making it easier and faster to organise political actions (for example, a Facebook event created by journalist Ilya Klishin played a key role in organising the first rally on Bolotnaya Square in Russia in 2011).

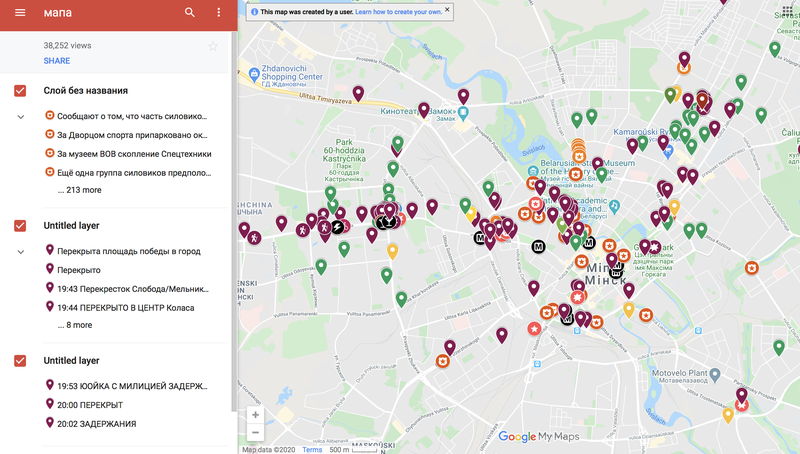

A live map of protests in Minsk, based on Google Maps.

On the other hand, these “connective actions” have vulnerabilities. For instance, sociologist Zeynep Tufekci has drawn attention to the cost of simplifying protest mobilisation. While technology makes it possible to quickly bring people onto the streets en masse without leaders or parties, these protests are much more difficult to translate into significant political change. This new type of protest can fade away without real results and as quickly as it emerges. In addition, technology creates new opportunities for surveillance and disinformation, as well as promoting insignificant forms of political participation like so-called “clicktivism” that carries few risks for participants and might be interpreted as a kind of simulation of real political activity.

Cycles of political innovation

Political crises are often accompanied by new waves of innovation that seek to change the balance of power between governments and protesters. For instance, in the 2019 protests during elections to the Moscow City Duma, one could observe several types of innovations in the coverage and coordination of protests as well as in technologies of mutual aid and surveillance. Most often, the authorities respond to the innovations of opposition activists with traditional force and repressive measures (ranging from arrests to shutting down the internet). But in some cases states have also employed innovative tactics, for example, using anonymous Telegram channels for provocation and disinformation. Recent events in Belarus can also be analysed in terms of the dynamics of political innovation. Many practices observed a year ago in Moscow are present in one form or another now in Belarus.

Firstly, citizens have learned to bypass internet blocks through a variety of tools: Belarusian users have made use of VPN and anonymisers like Psiphon. Protesters were also encouraged to use Mesh networks (the Bridgefy app) to communicate directly with each other if the internet was down. Telegram channels and telegram chats (which, with the support of the company, worked even in conditions of limited internet access) were actively used to coordinate actions and transmit information about the location of riot police, although the effectiveness of this communication in conditions of information overload and reliability remains in question.

At the same time, more complex crowdsourcing solutions for data collection were hardly used at all (with the exception of simple maps based on Google Maps). A little later, though, a crowdsourced “Map of Strikes” appeared.

Another issue has been that of mutual aid. Telegram channels showed information about access codes for buildings where protesters could hide (although this could also potentially be accessed by law enforcement agencies). The channels also reported where protesters could find water and medicine. Particular attention was paid to the coordination of assistance for those released from arrest.

The Telegram channel Okrestina Lists was used to search for detainees and publish lists of all people detained in the now notorious Akrestina temporary detention centre. Finally, special channels were devoted to the “de-anonymisation” of state officials involved in violence. It is also worth noting the global crowdfunding initiatives through which users outside Belarus have been able to help victims of state violence (for example, an initiative launched by activist Alexey Leonchik raised more than US$2 million).

However, protesters’ choice of technologies is not the most important thing at stake. A more significant question is which technologies are most fundamentally important for transforming a political crisis into an opportunity for change – in this case to prevent the continuation of the Lukashenka regime. This question is essential because the current Belarusian protests are taking place in the absence of formal opposition leaders (most of whom are in jail, while Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who is considered by protesters to be the winner of the elections, was forced to leave Belarus) or institutions. By their very nature, these protests can be considered fragile and vulnerable ”connective actions” – the kind that make it so difficult to transfer the power of protest into the domain of real political change.

Horizontal surveillance and the critical mass of state violence

Recent events in Belarus show the key role of the internet in shaping motivations for participation in protests. The initial motivation was election fraud. In the hours after the first results were announced, widespread evidence of the scale of falsification began to appear online. There were photos of final protocols showing a convincing victory for Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. The sheer scale of the falsification, above all, delegitimised the elections. But this was only the initial motive for the protests.

Soon after people started taking to the streets, there were reports of violent crackdowns on peaceful protests. Within hours, social media were flooded with evidence of violence. These kind of tragic snapshots of violence often quickly become symbols of a protest. For instance, during the 2009 protests in Tehran a video of the brutal murder of an Iranian woman, Neda Agha-Soltan, was seen all around the world. In the case of Belarus, the critical mass of state violence was unprecedented. Social media brought new evidence of brutality from police and security forces literally every minute, including the beating of bystanders with batons, people being assaulted from behind, and shooting at cars and residential buildings.

Belarusian Telegram channels, especially Nexta and Belarus of the Brain, became a stream of “reports from the battlefield”. This information flow was possible thanks in part to the failed attempt by the Belarusian authorities to completely block internet access. Another reason was the fact that violence was happening not only on the approaches to public squares, but everywhere, in courtyards and on the street. Police violence was witnessed by ordinary people filming from the windows of their homes and drivers who filmed what was happening in the opposite lane. This evidence was joined by footage of the ill-treatment of detainees in isolation, also filmed from the windows of neighbouring apartment blocks.

All this played out in an “a reverse Panopticon” effect: in an environment full of mobile phones, dashcams and CCTV, not only can the state observe its citizens, but citizens can also effectively monitor the state. The response to state violence is this “horizontal surveillance”. The critical mass of evidence of violence becomes the new key trigger for protests and general public mobilisation. Crimes against humanity replace election fraud as the main focus. Later, this evidence can potentially be used to prosecute the perpetrators. A number of organisations have already announced a joint open-sourcing initiative, whose goal is to systematically collect, verify and analyse all data on human rights violations committed during the suppression of the Belarusian protests.

Everywhere and nowhere

American political scientist Elmer Eric Schattschneider argues that one of the main factors in the success of a protest is the “scope of contagion” of a political conflict.

Sometimes attempts by the state to limit the scope of citizen engagement through repressive measures have the opposite effect. For example, a number of studies show that internet shutdowns often serve to escalate protests, as the information vacuum forces people to take to the streets. There is still the question of what awaits those who leave their own homes. The brutal suppression of protest by the state creates a dilemma for protesters. On the one hand, the risk of participation in protests increases. Moreover, apparent success in suppressing protests can lead to an increase in the number of so-called “free riders” – people who hope that political goals will be achieved without their participation. On the other hand, the feeling that the number of participants is growing in response to violence and that the protest is gaining momentum becomes crucial if willingness to participate is to outweigh the “logic of risk”.

Social media turned out to be fundamentally important not for coordinating protests, but for creating a sense of its invincible growth. This applies both to the geographic spread of the protest and the diversity of participants – their location, gender, age and social status. Researchers speak of this as an issue of the “visibility” of protest: it is not enough to go out into the streets, but important to show this in such a way that it subjectively evokes for those remaining at home a feeling of mass participation. An example of a principled “technology of visibility” is the use of drones to photograph the size of a crowd from the air.

The authorities, meanwhile, strive not only to disperse people from the streets, but also to minimise the potential “visibility” of the protest. The problem of visibility becomes especially acute in a situation of hyperlocal protests. Unlike “one square” protests (as in Cairo or Kyiv), these cannot be shown in a single “drone’s eye view”. But the case of Belarus illustrates a solution to the “visibility problem”: the news feed formed by Telegram channels and local Telegram chat groups showed the protests taking place simultaneously in hundreds of locations.

Hyperlocality and multiple points of decentralised protest can often become an advantage for protesters – it is more difficult for the state to suppress such actions. However, in the past it was also difficult for such protests to create the effect of mass participation. As shown in Belarus, information technologies can compensate for this lack of the visibility of a “crowd on the square” by creating a mass effect through constant information flows and pointing to new sites of protest.

In the critical hours when riot police, using violence, were increasing the risk of participating in the protests and thus seeking to stop them, the opposite happened – the documented violence created a new motivation for mobilisation. The effect of the mass scale and geographic distribution of protests, as seen in the feeds of Telegram channels, exceeded the subjective threshold of participation – that is, the threshold beyond which the subjective feeling of danger of participation in actions is overshadowed by the willingness to go out because everyone was going out. The snowball mobilisation effect had begun. In the emerging information environment, people felt that, wherever they took to the streets, they would not be alone.

At the same time, the role traditionally attributed to social networks in the tactical coordination of protests may have played a secondary role, particularly during the first days of the protests. Some forms of online coordination were effective – for example, the emergence of closed women’s chats, created to organise chains of solidarity. At the same time, many other chats often could not cope with the chaos of conflicting mobilisation messages and instructions, which made it difficult to track the development of protests, including for the authorities.

Coordination is important when relatively small groups are protesting and there is no critical mass of participants. In this situation, it is possible to resist the more powerful pro-government resources precisely because of the increased efficiency of the action. However, when the ubiquitous chain reaction of involvement begins, numbers of protesters become more important than coordination. Going out onto the streets and squares, people self-organise without the help of information technology, and internet blocks only contribute to this scenario.

The mobilisation effect was also facilitated by the viral spread of stories showing the moments of protesters’ victories over security forces, footage of people beating away attempts to detain them or stories of law enforcement officers taking off their IDs, uniforms or epaulettes as a sign of non-violence.

Transformed from object to subject

Of course, the success of the Belarusian protests cannot be attributed to information technology alone. This is primarily the result of political and social factors that arose during the totalitarian rule of Lukashenka, and especially during his recent election campaign. Moreover, we still do not fully know what the political outcome of the current events will be. However, what is happening in Belarus is an important example of how information technology can help turn a political crisis into an opportunity for political change, despite the fragile nature of “connective action”.

Here let me recall the paradox described by the Strugatsky brothers and brilliantly shown by Andrei Tarkovsky in the film Stalker. Entering “The Zone”, the main characters find themselves far from “The Room”. However, the direct path to it is not the shortest. It is the same with protests: having entered the square immediately, the crowd may find itself in the trap described by Zeynep Tufekci. It may fail to gain critical mass, lose energy and disintegrate before it can achieve its political goals. The “path to the square” through which Belarusians have passed has helped them to avoid this trap – if at a tragic cost.

In the new information environment, the violence used against participants in the course of hyperlocal dispersed protests is becoming less effective at suppressing them. Quite the opposite: violence is becoming a new motive for people to take to the streets. The intimidation effect is neutralised by the general mobilisation effect and contributes to a sharp increase in the scope of involvement. It is at this point that a chain reaction begins, which is increasingly difficult to stop: repression becomes ineffective and even counter-effective; a crowd of protesters turns from an object of persecution into a subject of the political process. Over time, the crowd becomes ready to enter the central square, uniting hundreds of hyperlocal protests into a single column. It was this path to the square, laid in the first five days after Belarus’ presidential elections, that turned the crowd into a political force capable of escaping the trap of horizontal mobilisation and bringing about real change.

Will Belarusians be able not only to complete the impossible task of removing Lukashenka, but also prove the senselessness of violence as an instrument for achieving political goals? Perhaps, just like the “end of history” thesis, it is too early to announce the “end of political violence”. But events in Belarus may push other authoritarian regimes to rely less and less on traditional force to suppress internal discontent, instead investing more and more resources in innovative forms of control designed to create new, invisible barriers to the “path to the square”.

Post a Comment