These spiritual, pseudoscientific groups are domesticating QAnon narratives for non-American audiences

A popular image of Ashtar Sheran, an alien according to some New Age beliefs. Image by www.angels-light.org. The owners of the website encourage the dissemination of their library of illustrations.

Some two dozen people dressed in yellow and green gathered at Rio de Janeiro’s Copacabana beach on August 23, in what seemed like yet another pro-Bolsonaro protest, commonly held to praise Brazil’s president since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

But when a young man wearing a T-shirt with a skull-shaped image of the US flag began to speak, it became clear that there was something different — and slightly odd — about this gathering.

“I’m going to use code for a few words so social media doesn’t censor me,” the young man says in a video of the event he posted on Facebook. He shows the group a poster with the heading “To Research,” bearing a list of terms most likely unknown to many Brazilians—“New World Order,” “Pizzagate,” “Operation Storm.”

These terms all relate to QAnon — a US-born conspiracy movement that postulates that US President Donald Trump is fighting a global elite that runs a centuries-old pedophilia ring through a secret operation called “Storm.”

The movement evolved out of the 2016 Pizzagate conspiracy theory, which claimed that Democratic Party officials, including Hillary Clinton, were running a secret child trafficking scheme run in the basement of a pizza parlor in Washington, DC. About a year after the theory was debunked, an anonymous user identifying as “Q Clearance Patriot” posted a cryptic message on the 4chan imageboard suggesting Clinton would be arrested in the following days — which never materialized.

“Q” has subsequently posted several times claiming to have critical intel, and in the past three years, Q's anonymous followers have coalesced into a global collective delusion who puzzle over QAnon “drops,” with a presence on every major social media platform.

QAnon emerged in the US, but its plasticity makes it easily adaptable in a Brazilian context. President Bolsonaro — a Trump-worshipping, coronavirus-skeptic — rode to power on the promise of ridding Brazil of corruption, leftism, and other evils, and whose legion of highly-connected supporters vehemently distrust traditional media.

It isn't surprising that QAnon terms would eventually be slapped onto protest signs at a pro-Bolsonaro gathering in Copacabana beach. What is perhaps somewhat surprising is the name of one YouTube channel, written on one of the signs amid a list of must-follow QAnon YouTubers: “Ensinamentos da era de Aquário,” or “Teachings of the age of Aquarius” in Portuguese.

Although that name doesn't immediately signal QAnon lore, this is one of the largest YouTube channels that openly supports QAnon in Brazil. Its owner, Luciano Cesa, has amassed a legion of 200,000 subscribers in less than two years, and his success signals a growing interest — especially among Brazilian New Age groups — in the movement's beliefs.

These spiritual and pseudoscientific communities, which encompasses a range of practices such as shamanism, crystal healing, reiki, yoga, and numerology, are playing a prominent role in introducing and domesticating QAnon narratives to non-American audiences.

From New Age musician to QAnon influencer

Luciano Cesa explains the meaning of a famous David Dees illustration on QAnon to his Brazilian followers. More about Dees here and here.

Long before Luciano Cesa became a QAnon adherent, he founded a music label called “New Age Music,” producing over 15 albums. Cesa has played in various bands, weddings, and public schools around his home state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil’s southernmost.

In November 2018, Cesa posted one of his first videos with spiritual content called, “The divine intersection in Brazil’s liberation,” in which he praises Bolsonaro’s recent victory and then shares a slew of New Age and self-help content.

On April 7, Cesa published a video with direct QAnon-related theories called “Armed forces in action in the whole world,” claiming that Trump was preparing to conduct “mass arrests worldwide.” His channel exploded — the video attracted tens of thousands of views (197,000 to this day), compared to other videos that barely passed the 10,000-view mark.

The data below, generated social media analytics tool Popsters, shows the exact moment of the explosion:

Data from social media analytics tool Popsters on the channel “Ensinamentos da Era de Aquário.”

From that moment, Cesa has published a plethora of specifically QAnon-related videos, which frequently attract more than 100,000 views.

In late May, Olavo de Carvalho, a former astrologer largely credited with being Bolsonaro’s ideological guru, shared a video by Cesa.

In June, Cesa began offering live broadcasts to give his viewers updates on QAnon-related theories, supported by PowerPoint slides with information allegedly received from “privileged sources.” Cesa takes questions from the audience through live chats and solicits donations through YouTube Giving.

Cesa serves up a version of the usual QAnon menu: COVID-19 is a false crisis created by the “dark elite,” interchangeably referred as “reptilians,” “deep state,” “the Illuminati,” and “the New World Order”; German Chancellor Angela Merkel, US Senator Bernie Sanders, and US actor Angelia Jolie, among other personalities, have been arrested and charged with child trafficking and their images that appear in the media are clones or doppelgängers; Recent earthquakes in Central America were caused by explosions in the “secret tunnels” used to smuggle children; one of those secret tunnels is underneath the famous Sugarloaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro.

Cesa did not reply to requests for comment on his work by Global Voices.

In one significant sign of domestication of QAnon theories, Cesa claimed, on live broadcasts on August 23 and August 26, that João de Deus, Brazil’s disgraced spiritual leader arrested in 2018 after more than 500 women accused him of sexual assault, had accepted a plea bargain deal in which he would reveal that he used to organize orgies with minors for Brazil’s Supreme Court Ministers (Brazil's Supreme Court is seen as an enemy of Bolsonaro by his supporters).

Deus did not negotiate any plea bargain deal with authorities, according to fact-checking agency Aos Fatos.

Still, Cesa presented a single tweet by Alan Lopes, a Bolsonarista influencer, as evidence. The baseless claim spread virally on WhatsApp in Brazil via memes claiming that Deus was “the Brazilian Jeffrey Epstein.” Cesa has since deleted the two mentioned videos, but they were both re-uploaded by another account — likely one of his followers. Lopes has since deleted his tweet, but Google cache has preserved it.

Luciano Cesa shares a tweet by Alan Lopes as evidence that João de Deus, a spiritual leader who was arrested following accusations of sexual assault, would implicate Brazil's Supreme Court justices’ on a plea bargain deal. Deus has never signed any plea bargain deal with the authorities. Screenshot from YouTube.

Cesa’s videos stand out for the spiritualist, supernatural spin. He often offers live meditations for his followers. His worldview is underpinned by the idea that Trump, along with allies such as Bolsonaro, is a member of an “Earth alliance” who is helping a cohort of benign aliens to clean up dark forces and ultimately “transcend” to the Age of Aquarius, a period of enlightenment. While all of this might sound to many like something out of a space opera script, it’s recognizable to those familiar with decades-old UFO conspiracies.

“It’s difficult to map these communities,” says Victor Campanha, a researcher of sciences of religion at Federal University of Juiz de Fora, who studies UFO movements, “because people who gravitate toward what we call ‘New Age beliefs’ will never identify themselves as new agers. What some of them will say is that they have an independent spirituality.”

Campanha told Global Voices that one way such communities describe themselves is as “searchers” — searchers for truth, for self-improvement. “These are also strong sharing cultures, so, if a person does a course of, say, shamanic cures, it’s likely they will also teach their own course. That’s why there is so much decontextualization, sometimes of ancient practices, in those so-called New Age circles.”

As such, New Age communities have a few things in common with QAnon members, who often describe themselves as “researchers” open to new truths. QAnon conspiracies are often presented in incomplete tidbits — collections of loose terms and concepts which potential adherents are invited to explore on their own, and which they decontextualize and remix as they share their findings.

The idea of a secret government that rules everything from the shadows is also rife in New Age circles. “Those are communities that distrust institutions, such as conventional science and dogmatic religions,” Campanha says, “so, I can definitely see this culture easily transferring themselves to those conspiracy ideas, with politicians who portray themselves as “outsiders,” such as Trump and Bolsonaro, being seen as antagonists against this shadow government.”

Journey of a follower

Mara Carvalho, 60, is a psychologist, numerologist, floral therapist, tarot reader, spiritualist writer, and up-and-coming YouTuber from Santo André, Brazil. Together with her friend, Márcia Rodrigues, she runs a small YouTube channel named “Tips for a good ascension.” The pair have published 614 videos over the course of 12 months, attracting a little over 1,200 subscribers.

In the late 1990s, Mara Caravalho discovered the “Great White Brotherhood,” a theosophical concept referring to a group of enlightened beings (in many New Age communities, this is often used interchangeably with the Ashtar Command, a group of benign aliens).

“I see myself as a disciple of the brotherhood, who don’t require rituals. It’s a direct connection I have with the masters, and I’ve had this connection for the past 22 years,” she told Global Voices.

A majority of Mara Caravalho and Rodrigues’ videos feature them reading aloud texts about New-Age related topics. But in March 2020, with the start of the pandemic, they began to reference QAnon, in the form of mentions of “the cabal that rules the world,” and QAnon concepts like “the global reset.”

Then, on June 6, Mara Caravalho published a video titled “Q, the plan to save the earth.” In it, she reads a text she says is “the most important I’ve ever read on this channel.” She is apparently unaware that the text she is reciting is a Portuguese translation of the seminal QAnon video “Q, the plan to save the earth,” originally uploaded in June 2018 by “Joe M,” one the most famous QAnon accounts on the internet.

A few days later, Carvalho published a video called “Operação Storm,” referring to the QAnon belief in a massive clean-up of evil forces. In both videos, she references Luciano Cesa, who she says both she and Rodrigues follow closely because he gives “a spiritual dimension to that operation.”

“After following Luciano Cesa, we got access to information about this undoing of the pedophile network. And one day, the spirituality told me that I had to talk about those things as well, even though I didn’t want to initially,” she said. “We are in the third world war, a war with biological weapons and information and counter-information.”

When asked to describe her understanding of QAnon, she said: “For me, it’s a group that works for the light — that is helping to bring the truth to people.”

There are many New Age channels and pages similar to Cesa and Carvalho in Brazil, which freely share QAnon conspiracies, such as the following:

YouTuber Gledison de Paula, on his channel Ascenção Planetária (Planetary Ascencion in Portuguese), recites a “channeled text” (how UFO believers designate messages received from aliens) explaining how the Pleiadians (a group of benign aliens, according to the conspiracy) are involved in “operation storm.” De Paula also runs a 12,000-member Facebook group and a Telegram channel.

Vilma Capuano, with 25,000 followers, is interested in shamanism, numerology, reiki, among others. She claims in this post that COVID-19 stands for “certificate of vaccination with artificial intelligence,” a widely debunked conspiracy theory. The text received over 800 reactions and 153 comments and is likely a translation of an English-language text.

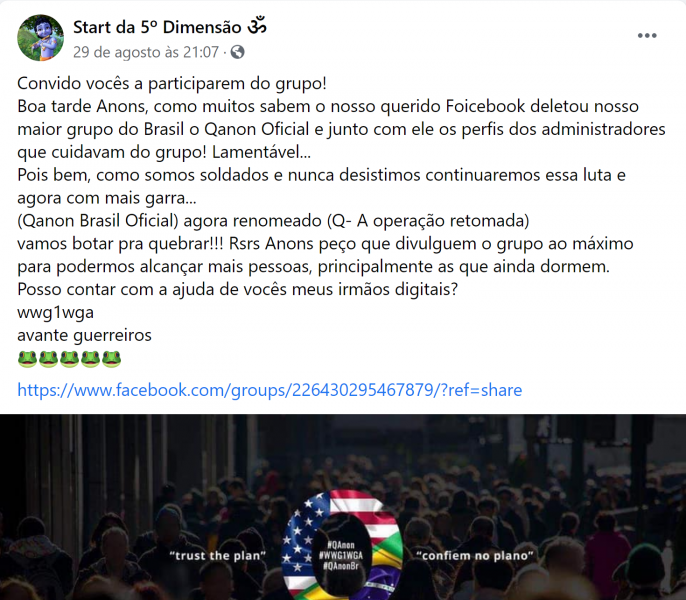

With 80,000 members, “Start da 5a dimensão” (Start of the 5th dimension) is likely one of the largest New Age groups in the Portuguese language on Facebook. In this post, the administrators announce that Facebook deleted their parallel QAnon group, and advertise the creation of a new group. QAnon hashtags and symbols fully present here.

It is easy to dismiss such communities as essentially harmless. But, as seen above, those groups have consistently helped spread COVID-19 disinformation. And even more worrying are the several cases of violence carried out by QAnon supporters throughout the world.

In February, a gunman in Germany opened fire in two shisha bars in Hanau, Germany, killing nine people. He left behind a digital trail of worship of US President Donald Trump and beliefs about QAnon’s child trafficking conspiracies.

New Age communities, international in scope, provide a safe avenue for QAnon theories to spread from the US and adapt to contexts such as Brazil, while tapping into an audience that may or may not be part of Bolsonaro's main support base.

In fact, it is precisely communities who claim to be apolitical, such as New Agers, who are especially vulnerable to the influence of fascist movements.

On August 20, at a White House briefing, Donald Trump was asked directly about QAnon for the first time. “I don't know much about them, except that they like me very much,” he said. When a reporter followed up with an explanation that the crux of the theory was that the US President was fighting a cabal elite of child abusers, he answered: “I don't know about that, but is that supposed to be a bad thing?”

Trump's clever reply — which simultaneously evaded the question while appearing to express support for the movement — highlighted the challenges that both reporters and society at large face when confronting conspiracy theorists.

Post a Comment