‘We'll reach a stage where we may not find Panadol’

Pharmacists protest in Al Jazeera State, Sudan. Photo by Sudan Pharmacists’ Central Committee, Al Jazeera, Sudan, June 12, 2020, used with permission via Facebook.

Do you have a headache? Imagine not being able to access Paracetamol, Panadol, or Vitamin C. Yes, this is the reality in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, a nation with a critical medicine shortage.

The pharmaceutical crisis began in 2016 when the government announced that it had removed subsidies for all medicines. The opposition called for civil disobedience to put pressure on the government to reverse its decision, but it did not back down. Since then, medicine prices have risen exponentially in Sudan while the government has done little to ease the strain.

To make matters worse, the government’s central bank lacks the foreign currency necessary to purchase essential drugs. Sudan has about 27 pharmaceutical firms that produce about 900 types of medicines, as well as 48 medicine companies, but this does not meet all of Sudan’s needs. Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, Sudan's largest drug manufacturer, was destroyed by a United States missile attack in 1998.

Most of these companies import medicines and medical supplies via the Central bank of Sudan or CBOS, which faces a severe shortage of foreign currency.

On June 11, the Professionals Pharmacist Association and Sudan’s Pharmacist Central Committee, members of the Sudanese Professionals Association, declared a silent protest to put pressure on the government to provide a monthly budget for drugs estimated at 55 million dollars.

The group created a hashtag #الدواء_معدوم which means “medicine is non-existent.”

دكتور أكرم

أما بعد

نساندك في الحق و نهديك عيوبك بما يرضى الله

نعم انت مقصر

#الدواء_معدوم ومهما اعترفنا بالأسباب فالحل يظل في يدك او واجه الشعب بشفافية بما يدور في الكواليسالمواطن يموت

— Dr Ahmed McLad د. أحمد مَقلَد (@McLad84) June 11, 2020

Dr. Akram [Health Minister]: For now, we support you in the truth and guide you with your faults to the satisfaction of God. Yes, you are deficient and no matter how we admit the reasons, the solution remains in your hand, or the people transparently face what is going on behind the scenes. The citizen dies.

In April, the National Council of Pharmacy and Poisons agreed with the Chamber of Medicine Importers to raise the price of importing medicines by 16 percent and raise the profit margin for pharmacies to 20 percent, applying this increase retrospectively to create a profit margin for pharmaceutical companies.

But the next month, Minister of Health Dr. Akram El-Tom canceled the decision, justifying that the price of the medicine had increased too much for an everyday citizen to afford. This decision reflects unrest inside the ministry.

On May 18, the CBOS canceled 10 percent of proceeds from exports intended for drug imports, which affected the drug stocks.

Dr. Ameen Makki, a Sudanese pharmacist and political activist, posted on Facebook:

We sat with the Minister of Health in several sessions since September 5, 2019, before he became a minister, and we presented him with all the medical problems in the last five years, proposals for solutions, and even the amount of medicines in the storages and we told him that we will reach a stage that we may not find Panadol. All these sessions were attended by experts and consultants working in this field. All plans were aimed at providing an effective, safe and affordable medicine for citizens. In February, Sudan’s Central Pharmacists Committee invited a conference inviting all partners from the National Council of Pharmacy and poisons, the Ministry of Finance, the Central Bank of Sudan, the National Fund for Medical Supplies, members of the Sovereign Council and the Ministry of Health, but the Minister of Health did not attend and did not send a representative. The minister's dealings were with complete neglect of this file, and we every day sounded the alarm to him until we reached this critical stage…

Last July, the United Nations also affirmed that Sudan faces a critical medicine shortage due to its ongoing economic crisis.

Pharmacists in Sudan protest against the critical medicine shortage in the country. Photo by Sudan Pharmacists’ Central Committee, Khartoum, Sudan, June 12, 2020, used with permission via Facebook.

How did a critical medicine shortage begin?

In December 2018, the federal Minister of Health Mohamed Abuzaid acknowledged that the “medicine shortage in Sudan is serious,” and held the CBOS responsibly.

According to a March 2020 report by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), Sudan’s economic crisis continues to impact the availability of medicines.

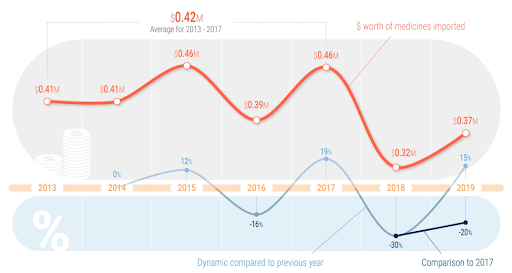

A 2019 CBOS foreign trade statistical digest shows that Sudan imported $367 million United States dollars worth of medicine in the fourth quarter of 2019. This is an increase of about $47 million USD (15 percent) compared to 2018, but it is $91 million (20 percent) lower, compared to 2017 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Screenshot from the UNOCHA situation report in Sudan, March 2020.

The scarcity of foreign currency has created a black market that caused inflation to reach nearly (118.18 percent) as of June 3, according to a monthly report on inflation in Sudan by professor Steve Hanke.

The black market serves as a short-term solution, enabling the medicine trade in Sudan to continue through small merchants who smuggle medicine from neighboring countries through luggage.

However, these drugs are not subject to quality and efficacy checks.

Smuggling has slowed down due to border closures on March 16, when Sudanese authorities closed borders to avoid the spread of the COVID-19, making it even harder to access critical drugs on the black market.

Figure 2: Sudan inflation rate, July 2017-June 2020, according to Professor Steve Hanke via Twitter.

The COVID-19 blame game

Since March, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit Sudan, the price of personal protective equipment (PPE) increased by more than 300 percent due to scarcity.

Medical services nearly came to a halt as many patients and doctors stopped going to hospitals and health centers out of fear of contracting the virus. As of June 18, over 8,000 people have contracted COVID-19 and nearly 500 people have died. However, there is no official account of how many deaths have occurred from other diseases due to the drug shortage.

Meanwhile, Sudanese social media has recently surged with condolences, including one from the minister of religious affairs acknowledging the deaths of several clerics.

The COVID-19 response has been fiercely debated in Sudan, where blame ping-pongs between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finance.

A leaked letter from the Minister of Health Dr Akram El-Tom.

In a now-leaked letter, Minister of Health El-Tom accused Minister of Finance Ibrahim al-Badawi of spending foreign aid earmarked for the coronavirus on electricity and envoy dues instead.

The letter also accused Badawi of not paying the nation’s medicine bill since December 2019:

I remind you that you promised to provide monthly 20 million dollars as a partial payment of the medicine bill …I remember that the time when the Ministry of Finance made individual decisions to determine the resources of other ministries has ended on the day that this government was sworn in after a revolution that sacrificed the blood of its martyrs.

Elbadawi at the Ministry of Finance responded:

The Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning flatly denies the rumor circulating that the Ministry of Finance has acted in any of the benefits or grants in kind or cash that were provided to Sudan to confront the coronavirus for other purposes than that. The Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning confirms that all these subsidies and grants that have reached Sudan have been fully utilized to confront this pandemic…

This blame-game exchange makes citizens wonder when and how this crisis will ever get resolved.

Post a Comment