A creative visual campaign reopens old wounds in Czech society

A large billboard representing Milada Horáková and a slogan beneath reading “Zavražděna komunisty” (Murdered by communists) hanging on Prague Old Town Square. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

June 27 marks a special date in the Czech Republic: Remembrance Day for the victims of the communist regime (Den památky obětí komunistického režimu).

This year, it was commemorated with particular force because exactly 70 years ago, on June 27, 1950, Milada Horáková, a lawyer, politician and Nazi resister, was hanged along with others after a show trial under the orders of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

Remembrance Day was inaugurated in 2003 with the date chosen to honor the memory of Milada Horáková.

Feminist, resister, survivor

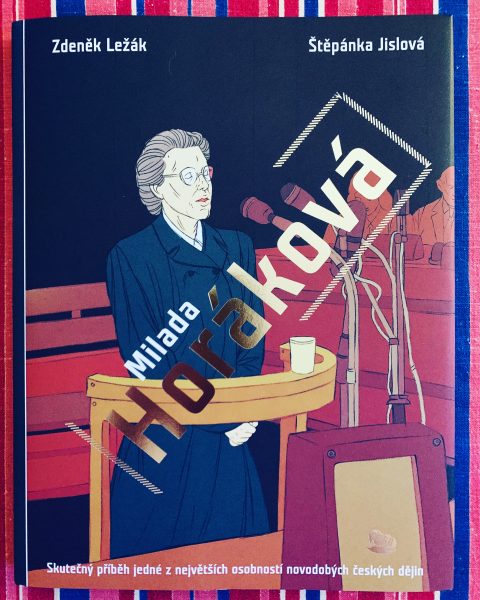

Comics released in 2020 to mark the 70th anniversary of Milada Horáková's death, by Zdeněk Ležák and Štěpánka Jislová. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Milada Horáková‘s biography reads like a Hollywood movie: She was born in 1901, in what was then still the Austrian-Hungarian Habsburg Empire, into a middle-class family. She managed to study law at a time when very few women did and became active in women's emancipation movements.

Czechoslovakia, which emerged in 1918 from the Habsburg Empire, allowed women's vote as early as 1920, ahead of many other European states, thanks to Senator Františka Plamínková, the founder of the Women's National Council for whom Horáková started working in 1924.

From 1927, she worked in the social welfare department, promoting reforms aimed at women's equality. During World War II, she entered the resistance movement against the Nazis, along with her husband, but both were arrested in August 1941.

Horáková, who spent four years in camps and prisons, managed to represent herself at her own trial, and therefore avoided the death penalty. She returned to her work in 1945, and agreed to run as a member of parliament for the Czech National Socialist Party. She quickly became a target of the communists for her outspoken criticism of their agenda to curb democratic freedom in post-war Czechoslovakia.

She was eventually arrested on September 27, 1949, along with her husband and others, and charged with treason in June 1950 in a sham trial that was meant to show that the new regime would not stop at anything — including sentencing women to death — to impose its policies, with zero tolerance for the slightest criticism. The trial was scripted on similar parodies of justice already carried on in the Soviet Union.

She gave her final speech on June 8, 1950, during her trial, in which she refused accusations of treason with strong determination. Here is a segment of her speech in this video in Czech:

She was eventually sentenced to death. On June 27, she was given 20 minutes to see her sister and her daughter before she was hanged. She was cleared of all accusations posthumously in 1991, when she was awarded by President Václav Havel the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the highest state honor made for outstanding contributions to the development of democracy, humanity and human rights

In 2017, an English-language movie was made about her life by David Mrnka:

A still painful assessment: 40 years of communism

After communism collapsed in Czechoslovakia in 1989, authorities faced a difficult choice when justice for victims of the previous regime surfaced. Eventually, they opted for a process of non-judicial lustration — the purge of government officials — that prevented all employees of communist-era state security from holding office in the higher levels of civil service, including the judiciary, until at least the year 2000. In Czechoslovakia, this status lasted until 1992, and from January 1, 1993, in the Czech Republic.

The government also allowed the Communist Party to continue to function. The Party, renamed the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (known in Czech under its acronym KSČM), remains small during elections but plays a key role in tipping alliances and voicing support for Moscow and Beijing influence in the Czech Republic. It now holds 15 out of 200 seats in parliament.

A number of political forces and civic movements have recently stepped up their criticism of KSČM and the communist legacy in Czech society. This year, the civic movement Dekomunizace (De-communisation) launched a visual campaign across Prague, the capital, hanging large size billboards with images of Horáková and strong messages such as Zavražděna komunisty (“Murdered by communists”).

While some higher education institutions and political forces support the campaign, others have described it as offensive and divisive by reopening old wounds.

The most outspoken critic has been KSČM, which stated in a Facebook post:

Krajský výbor KSČM Praha důrazně protestuje proti zkreslování a přepisování historické pravdy a proti rozdmýchávání antikomunistické nenávisti, která je opět vyvolávána v hlavním městě.

Současná agresivní kampaň zaměřená proti KSČM zapadá do scénáře usnesení Evropského parlamentu „O významu evropské paměti pro budoucnost Evropy“, přijatého v září 2019. Toto usnesení staví na stejnou úroveň komunistickou a nacistickou ideologii, socialistické a nacistické režimy.

The regional committee of KSČM for Prague strongly protests against the distortion and rewriting of historical truth and against the spread of anti-communist hatred, which is again fomented in the capital. The current aggressive campaign against the KSČM fits into the scenario of the European Parliament resolution ‘On the importance of European memory for the future of Europe,’ adopted in September 2019. This resolution puts communist and Nazi ideology, socialist and Nazi regimes on an equal footing.

Journalist Petr Šabata wrote in a column published on the portal of Seznam Zprávy on June 26:

Ano, Milada Horáková byla zavražděna komunisty. Ale zúžit vzpomínku na ni jen na komunisty by bylo vůči této nezlomné ženě znovu nespravedlivé. Protože Milada Horáková byla bohatá originální osobnost a její osud má několik vrstev a nabízí mnoho inspirace.

Yes, Milada Horáková was murdered by communists. But to reduce the memory of her life to the communists would be once again unfair to this unbreakable woman. Because Milada Horáková had a rich and original personality and her life has multiple layers and provides a lot of inspiration.

For Michal Gregorini, the official representative of the movement Dekomunizace, the aim of the movement is to prevent the loss of historical memory, as he explained in an interview to the news portal iRozhlas on June 22:

Proč Milada Horáková? Ono je to teprve sedmdesát let. Zdá se to, jako kdyby to bylo strašně dávno, v minulém tisíciletí, ale moje máma to pamatuje, takže je to hrozně nedávno. Proto připomínáme Miladu Horákovou.

Why Milada Horáková? It was just 70 years ago. It might seem as being a very long time ago, in the previous millenium, but my mum remembers it, so it is actually in the very recent past. That is why we remind everyone about her.

The campaign also included an “audio-collage” as sound segments of her trial were broadcast in Prague metro on June 27.

Post a Comment