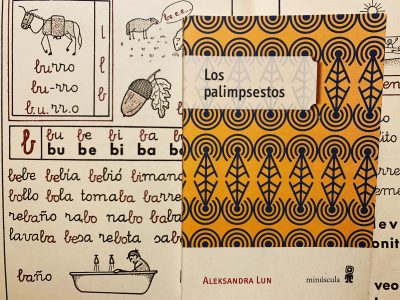

Cover of Aleksandra Lun's novel “Los palimpsestos” in the original Spanish. Photo by Filip Noubel, used with permission.

Exophonic writers — that is, authors who write in a language that isn't their mother tongue — are a growing phenomenon in the 21st century, as migration takes a global scale and flows in various directions. It is important to make a distinction between authors who grew up in a multi-language environment, such as the often-mentioned Vladimir Nabokov, and authors who learned a language as adults and decided to write in what was a foreign language until late in their lives. One contemporary example of the latter case is Jhumpa Lahiri, a Bengali-American English-language author who now writes in Italian.

Another example is Aleksandra Lun, a native speaker of Polish and accomplished translator who one day decided to write fiction in Spanish, a language she mastered only after she turned 19. Her novel itself is a reflection on linguistic hybridity: “The Palimpsests,” released in 2015, tells the story of Czeslaw Przęśnicki, a Polish writer who migrates to Antarctica where he learns the fictional local language and writes a novel in it.

I talked to Lun about what motivates a writer to embrace an initially foreign language, and what it means to be a celebrated author outside of one's home culture.

Filip Noubel: You were born a native speaker of Polish, learned Spanish at the age of 19 while working in a casino to finance your studies in Spain, and today you are a celebrated and translated Spanish-language writer. How did this linguistic shift happen?

Aleksandra Lun: If we think about the Czech proverb that says that we live a different life in every language we know, I have had several lives, as I am sure many of Global Voices’ readers have had too. According to my calculations, I could be now 136 years old, which is frustrating since I don’t seem to be receiving any retirement benefits! The way I see it, there has been no linguistic shift, only the fact that in one of my lives I am a writer.

We can see languages as multiverses, a concept from a theoretical framework in physics called string theory. Like a multiverse, each language describes a different story, a story that happens simultaneously to all other stories. Writers are just the people who put those stories down.

FN: Do you also write in Polish? Many bilingual or exophonic writers often say that writing in a language that is originally foreign creates a distance which helps them to express things that would otherwise be difficult in their native language. Do you agree with this?

AL: For “The Palimpsests,” I researched into cases of authors who changed languages: illustrious immigrants like Samuel Beckett, Ágota Kristóf, Joseph Conrad, Vladimir Nabokov, Emil Cioran and others. I didn’t find any common denominator since they all had their own reasons not to write in their mother tongue. Some took a time-specific decision to change, others did it naturally. Some switched languages for personal reasons, others for commercial ones. Joseph Conrad used to say that he didn’t choose English at all – it was English that chose him. He also said that English was the only language he could have ever written in, while Ágota Kristóf claimed she would have written in any language. There is a variety of choices and motivations, and they are all legitimate.

I cannot say that I don’t write in Polish since in my translations I write in Polish all the time. But my muses talk to me in Spanish, so translating their voice into Polish would just be double work. Regarding the distance that writing in another language is supposed to create, I think it all depends on the relationship you have with it. To me, Spanish is the most natural choice. Using it is no stranger than brushing my teeth – I might not receive retirement benefits, but I am proud to conserve my own dentition.

FN: You also work as a professional translator. How does that shape your relationship with languages?

AL: A translator’s work reminds that of doctor Frankenstein’s, since you kill a text in one language and resuscitate it in another. You cut your victim in pieces, put them back together, and wish that they leave your clinic looking better than the patient of Frankenstein. In the process you lose some peace of mind and a lot of preconceived notions about your own language. It is a happy loss since it takes you out of the story of one specific culture and opens you up to a much bigger, common story.

Now you understand what happens under the skin and you start seeing languages beyond the superficial layer of vocabulary and its pronunciation. You see the organs and the connections between them, aka syntax, and you understand that they are just one of many options. And you start asking yourself questions. Why do some languages use definite and indefinite articles? At some point there had to be a powerful and mysterious need to divide reality into “things we know something about” and “things we know nothing about”. As someone who comes from Slavic languages, where we only see “things,” I find it fascinating that we grow up in such different realities.

FN: In your view, what does it mean to “master” or “own” a language?

AL: In Europe or the US we seem to be obsessed with “speaking” a language, the ultimate ownership as opposed to thinking, dreaming or writing in it. Beyond this narrative, which is an effect of the Western world’s dictatorship of extroversion, a language is simply a world that you choose to live in. If you live in that world, you own its language.

FN: Your book is extremely funny, but you also touch on sensitive issues: identity, rejection, migration, exile and the desire to integrate. How does language relate to those issues?

AL: Humour is an effective narrative tool since it brings things back to proportions. When you are an immigrant the last thing that is expected from you is to be funny. If you enter another culture, you are expected to behave as if you were invited to a formal dinner at your auntie’s: sit properly, eat up what you are served, be silent and smile a lot. If you have any interest in culture, you can listen to what the auntie’s intellectual friends have to say, maybe take notes and later try to translate them for your less fortunate friends, the ones that have not been invited. What nobody expects you to do is to arrive at your auntie’s disguised as SpongeBob, sit whenever you please, eat noisily your own vegetarian burger and start telling intellectual jokes.

Equality is difficult to achieve without humour because humour itself is a form of equality.

FN: Your first novel was translated into English and French, and a Dutch translation is underway. How do you prefer to be described? As a Polish writer? A Spanish writer, since your upcoming second novel will also be written in Spanish? Or just a writer?

AL: I can be described as Jack the Ripper, if that satisfies the person describing me! I know that I will always be classified as belonging to this or that other culture, but it doesn’t mean that I need to identify with a label. In our impermanent world, nationality can seem a solid and objective category, but it is one of the least objective ones. It only describes one of your external characteristics from a historical perspective. Your passport says nothing about who you are now.

The concept of national literature is itself an extravagant one. No other art field has been divided into these categories – we don’t hear that much about “Lithuanian rock bands” or “Nigerian photographers”, do we? There is a logistic reason behind a division into nationalities, since a book is coded in a language and needs to be translated to reach audiences that don’t understand it. But once it is re-coded, the human experience it contains doesn’t differ from the one in a book published across the border. A passport itself is not a very interesting read, even if the airport queue is very long. I strongly recommend reading shampoo labels in the shower instead.

Post a Comment