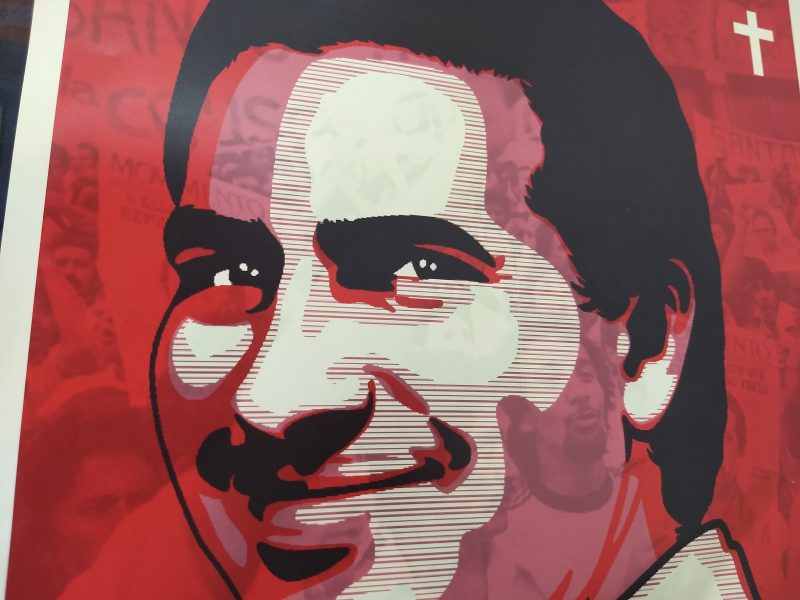

Santo was handing out pamphlets when he was shot by the police in 1979

A union leader died in 1979 during the military dictatorship. Image: Henrique Sales Barros/Agência Mural, used with permission.

This story was written by Henrique Sales Barros. It is published here via a content-sharing partnership between Global Voices and Agência Mural.

On October 31, 1979, Santo Dias Filho — or Santinho, as he is known — and Luciana Dias were, respectively, 13 and 11 years old.

That day, in the middle of a crowd of 30,000 people, they were in a car with the then Archbishop of São Paulo, Dom Paulo Evaristo Arns, on their way to Sé Cathedral. There, they participated in the funeral mass of their father, Santo Dias, who had died the day before at a workers’ protest.

Santo was distributing pamphlets at the door of the old television tube factory Sylvania, in Campo Grande, southern São Paulo, when he was shot in the back during an attempt by police forces to repress the striking workers.

As well as being a union leader, Santo Dias also acted as community leader along with his wife, Ana Dias, in the Vila Remo neighbourhood where they lived, in Jardim Ângela district, also in the capital’s south, and was a member of Brazil's Workers’ Pastoral.

Santinho and Luciana are now adults of 53 and 51 years old. Together, the siblings are the main figures of the Santo Dias Committee, which promotes and helps in the organization of events to preserve the metalworker’s memory.

Today, Luciana Dias is the educational coordinator of a school in Jardim São Luís, in southern São Paulo. | Photo: Henrique Sales Barros/Agência Mural, used with permission.

The committee, created soon after Santo's death, traditionally organizes an event in his memory every 30 October, at 2 p.m., in front of where the Sylvania factory used to operate, on Quararibéia Street. Today there is a residential condominium there.

On the tarmac, people paint, in red, the words “here the Christian worker Santo Dias da Silva was murdered, on 30 October 1979, by the military dictatorship.” From there, they head for Campo Grande Cemetery, about 500 meters away, where Santo's body is buried.

When Santo Dias died, 15 years had passed since Brazil’s 1964 military coup that deposed President João Goulart. The country was ruled by General João Baptista Figueiredo, at a time when political opening and re-democratization were beginning to be discussed. However, it was only in 1985, six years later, that a civilian would again hold the presidency.

For Luciana Dias, the group is necessary so that her father's story does not fade away. “He was a voice that was silenced by the dictatorship, and a silenced voice always has a lot to say,” she said.

Committee meetings are held in a room in the Holy Trinity Convent, in the capital’s southern Santo Amaro district. Santo Dias arrived in this area when he came in the city as a migrant from Terra Roxa, a town in the interior of São Paulo state, in 1962.

Anybody interested in participating in the meetings is welcomed. “There [in the meetings of the Committee], there are priests, bishops, university students, friends of Santo,” says Santinho.

They leave the conservation of documents to Cedem (Documentation and Memory Center) of Unesp (São Paulo State University), which keeps more than 3,500 documents, including texts, photographs, and videos, and others, related to the worker. The archive can be viewed at Cedem's headquarters in Praça da Sé, in downtown São Paulo.

Luciana Dias thinks leaving these files with Cedem's is the best way to preserve them. “There everything is well kept, sterilized, and acclimatized. Here [with the family] all this material stayed in cardboard boxes,” she recalls.

Santinho graduated in architecture and designed his own house | Photo: Henrique Sales Barros/Agência Mural. used with permission.

This year, the family has often split itself to attend the numerous events happening, sometimes on the same day and at the same time.

“There's a lot that happens that we, the Santo Dias’ family, don't ask. There are other people, from other places, who come to us and say ‘look, come here, we'll pay homage to your father,'” said Santo Filho.

On Saturday 26 October, for example, Santinho went to São José dos Campos city, a one-hour drive from São Paulo, to participate in an event by the Drivers’ Union in honour of his father. Meanwhile, Luciana went to the Memorial of Resistance in central São Paulo, where a detention centre of the dictatorship used to be, to participate in the launch of the second edition of the biographical book “Santo Dias: When the Past Becomes History.”

The book was written by Luciana with the journalist Jô Azevedo and the photographer Nair Benedicto. The first edition was released in 2004, and the book has more than 60 testimonies from religious people, family, friends, and retired workers who were close to Santo.

Luciana says she grew up having the idea of writing a book about her father: “Stories of bosses, barons and colonels we already have in heaps, but the story of a worker is never valued as much,” she said.

Memories for the future

Asked about how young people from the outskirts have been involved in keeping their father's memory alive, Luciana recalled when she went to see a play in February based on his biography, staged by a youth group from the Capão Redondo Cultural Factory, in southern São Paulo.

Luciana watched “Os Santos Dias do Capão“, directed by 34-year-old Ícaro Rodrigues, at Cia. Mungunzá in central São Paulo. When she was introduced to the young performers at the end of the play, she said they were surprised and thanked her for attending, amidst tears and smiles. “It was emotional,” she said.

She also mentioned the coordinators, teachers, and students of Ubuntu, a network of pre-university courses in southern São Paulo, of which one of the branches carries her father's name. They worked with the committee and created a poster with a QR Code which links to a page with information about Santo Dias.

When asked, Santinho was confident that his father's memory will be maintained even if he, his sister or people who had close contact with Santo are no longer alive. “The memory of Santo is no longer ours, his family’s: it is the world’s,” he said.

Post a Comment