Iran-born Forouhar has lived and worked in Germany since 1991

Parastou Forouhar, Water Mark, a tribute to the drowning refugees, 2015. “This work was created within the scope of the artist residency program of the Brodsky Center, Rutgers University, and in collaboration with Anne McKeown and Randy Hemminghaus, masters of papermaking and printing at the Brodsky Center.” Image courtesy of the artist.

Germany-based Iranian-German artist Parastou Forouhar is known for creating masterful artworks that embody “the synchronicity of harmony and beauty, along with other layers that display violence and a sense of insecurity and entrapment.”

Autobiographical in nature, her work uses a range of media including installation, animation, digital drawing and photography.

In 1991, Forouhar left Iran and settled in Germany where she received her postgraduate degree in art. Her work has been exhibited widely in galleries and museums in Iran, Germany, Australia and New York, and can also be found in the permanent collections of the German Parliament in Berlin and the British Museum in London.

Forouhar is a professor of Fine Arts at the Mainz Academy of Fine Arts in Germany. Her work currently appears in a group show of Iranian women artists titled A Bridge Between You and Everything, curated by acclaimed photographer Shirin Neshat at the High Line Nine gallery in New York City (November 7-December 14).

Excepts from my interview with Forouhar follow:

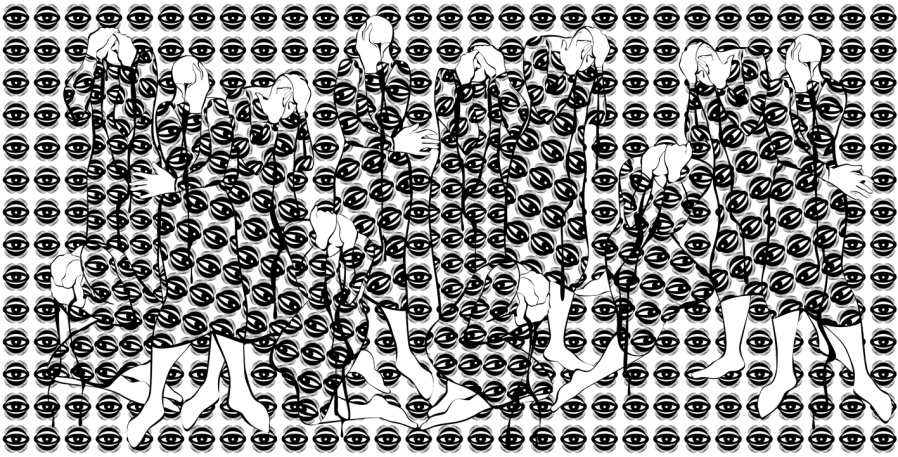

Parastou Forouhar, The Eyes, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Omid Memarian: Your “Eyes” collection evokes a police state and political repression. At the same time, the curved lines, recurring symbols and use of black and white show a harmony and tranquillity that clash with the meaning conveyed by the work. To me a viewer, it felt shocking. Iran is your preoccupation, but this narrative appears to be universal. What motivated this collection?

Parastou Forouhar: You pointed out something which I consider to be fundamental in a lot of my work: The concurrence of contradictory perceptions—the synchronicity of harmony and beauty, which are evident in the patterns and in their accumulation at first glance, along with other layers that display violence and a sense of insecurity and entrapment. Most of the latter layers become evident at second glance. In reality, by engaging the viewer in a work of art, I’m trying to show how to look at things and view them. I want to compel the viewer to look more carefully. As you in some way pointed out, this polarity and contradiction in perception, or the concurrence of opposing phenomena, is part of the human/social condition. You see its manifestation in Iran, but it’s not limited to a single society. Or, as you mentioned, it’s a universal narrative.

While working on the “Eyes” collection, which is one of my recent works, I was feeling a kind of intense crisis. There are social crises that stare at us and we seem to be fixated on them with anxiety, unable to overcome them. More than anything, this collection may have risen from the psychological and emotional crises that I’m going through, whether from the perpetual violence and oppression in Iran, the social collapse resulting from the various wars in the Middle East, growing confrontations with “the other” and fascism in Europe, where I live and work, or the coldhearted brutality against asylum seekers here and there.

Parastou Forouhar, RED IS MY NAME GREEN IS MY NAME III, 2015. Digital drawing on Photo Rag, 80 x 80 cm.Image courtesy of the artist.

OM: Politics, violence, discrimination, inequality and pain are major themes in your work, including “Eyes,” “Watermark” and “Red is my Name.” Sometimes they are clearly discernible, and sometimes more effort is needed to find the relationship between the various symbols and elements. What has led you to create such harmony in your repetitive symbols?

PF: Every artist works with life experiences. A person’s emotions and channels of understanding are formed by experiences. I grew up in a family and among a group of people whose main concern in life was to fight for freedom and justice under the dictatorship of the second king in the Pahlavi Dynasty. My father and mother and many of the people around me spent part of their life as political prisoners. In my youth, I witnessed the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq war, along with the brutal suppression of political opponents by the Iranian government, followed by migration and expulsion from my homeland… These situations in life shaped my human emotions and gave rise to my art. My artistic language and forms are based on ornaments and patterns which I gradually picked up over the years and tried to use to express my art. The ornamental structure allows me to present a mixture of visible and hidden meanings, to create beauty, balance and harmony with details that make you feel trapped in an organized turmoil and chaos. I try to create the potential for suspension between contradictory states that will emotionally and psychologically engage viewers and make them ask questions. From a technical standpoint, many of these sets of works are digitally created and printed with wide use of computer programs.

Parastou Forouhar, Written Room. Photo credit: Marc Domage. Image courtesy of the artist.

OM: Many of your works are spacious. Instead of being framed and hung on gallery walls, they take over the entire gallery, so that the viewer feels a common experience.

PF: You can generate a more complex and compact connection when an art form engulfs the audience, rather than just being in front of you. I see this aspect being in harmony with my work. These site-specific works take over and transform the space. As an emigrant, space has always been a challenging element. I think the desire to transform space is, to some extent, related to the experience of immigration and the struggle to open up your own space. I think you can see traces of these special works when I first started as an artist after finishing my studies in Germany in the mid-1990s. I think my first work that had this special feature was “The Written Room.” It was initially presented in 1999 and most recently I performed it a few months ago. It has been my most traveled work.

Parastou Forouhar, four-part photographic work Friday. Image courtesy of the artist.

OM: Your parents were murdered in Iran by the regime’s security agents in 1988, and since then you have been seeking justice and accountability for these political crimes and have sought to keep the memory of your parents alive. How has this impacted your artistic activities?

PF: The political murder of my parents has undoubtedly burdened me with a heavy load that I will always carry. These kinds of tragedies stay with people. I have always tried to avoid being crushed by this tragedy and as a human being, to react in a socially responsible way. Throughout the years, I have stood by the relatives of other victims of political crimes in Iran in order to seek justice and develop a culture of remembrance. There is no doubt that I have become more political and the impact of it can be seen in my artwork. But at the same time, I have always tried to be mindful of the basic difference between politics and art, and avoided taking advantage of them in favorable or detrimental ways.

Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar were brutally murdered in their family home in southern Tehran on 22 November 1998. Dariush, 70, was stabbed 11 times. His wife, who was 12 years his junior, had been stabbed 24 times. Image courtesy of the artist.

OM: You are frequently traveling between Iran and Germany, as well as other countries. What impact has three decades of life, culture and travels in the West had on your identity?

PF: By now I have spent more than half of my life in Germany. This second half of my life has shaped my professional career to such an extent that when I think and speak about my art, I rely on German as my primary language. In Germany and other countries, I’m introduced as a German-Iranian artist. I see myself as an immigrant who belongs to different cultures. I am attracted to spaces that are in between. Given this background and life experience, my identity is a process that is affected by many things. It’s alive and fluid, as opposed to fixed or solid.

Post a Comment